Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

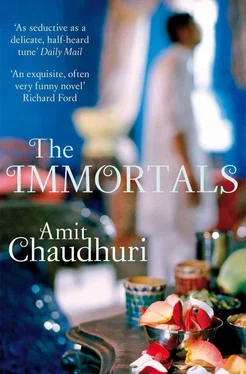

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Didi, you have to come!’ protested Sumati, Shyamji’s wife, laughing and shaking, pre-emptively, her head from side to side. ‘We will not do the grihapravesh without you!’

It was the exaggerated nonsense you expected from Sumati. But Mrs Sengupta agreed; for she also felt a faint quickening, a sense of being expected, of being special — it was the magic of arrival she loved looking forward to, the sort that attended, for instance, her visit to a poorer relation’s house because of some family occasion, when she was at once unremarkable, the same Mallika she’d always been, and transformed and unattainable, the Mrs Sengupta she was today. The flats had been bought in a housing development far away in Borivli in late November; now, before they were properly occupied, the grihapravesh ceremony — the ritual of making the dwelling auspicious — had to be performed. More nonsense, thought Mallika Sengupta; further expenditure on borrowed money. But, one December morning, they — mother and son (Mrs Sengupta, giving the lie to her claims of impatience, wearing a carefully chosen Kanjivaram silk, looking like the mistress of some mythic temple), set out in the white Mercedes-Benz; no question of Apurva Sengupta going — he was in meetings all day.

Borivli was only a name to them; they knew it existed somewhere beyond where their conception of the city stopped, but didn’t know where it was. Actually knowing anyone who lived in Borivli was out of the question. The driver seemed to be taking them toward the airport, but turned right into a busy junction; he went down a road full of small stops and traders’ outlets, then drove down a series of lanes, asking people for directions. It seemed, to their surprise — but, gradually, nothing was surprising — that more and more people lived here. The journey was full of stops and starts, and from time to time Mrs Sengupta said to Nirmalya, as if she were at the limits of her patience, that Shyamji’s family should have known better than to demand they travel to such a remote place. Finally, exhausted by monotony but awed, now and again, by how livelihoods and landscapes were obviously stretching outward, they came to the middle of nowhere, with three new buildings rising before them. They were the sort of building made for the lower-income bracket, plain stone, with only a hint of colour — faint pink — and tiny spaces for balconies. Yet they were noticeably new.

There had been an unseasonal drizzle in the morning, and it had left the ground muddy. Mallika Sengupta had trouble rallying her Kanjivaram round her ankles, and walking to the entrance; her low, two-inch heels marked her wavering, thoughtful progress on the soft ground. ‘Wait here,’ she said once, turning round to address the driver, as if she’d accidentally recalled his significance, and wanted to leave him with some instruction or assurance. He, emerging from the car and standing before it in his white uniform and cap, looked lonely and self-sufficient, an emissary who found himself in surroundings unworthy of him. Nirmalya, as he walked to the building, didn’t notice that anything was absent, but sensed there was something missing. There were no trees in the circumference that formed the horizon round these buildings.

Children were running up and down the gloomy staircase, yelling loudly and incomprehensibly — thin, not well-to-do, but energetic, stopping momentarily to stare at Mrs Sengupta with the familiar guileless gaze of people looking at someone who belongs to a different world — admiring, unresentful, a gaze, oddly, almost of recognition; and when Mrs Sengupta and Nirmalya came to the first floor, they found the door to one of the flats open, and the corridor lit by sunlight. Families of all hues, obviously related to Shyamji, seemed to have come to celebrate the move.

‘Didi!’ said Banwari’s wife, Neeta, when she spotted them, the pallu of her sari, as ever, shadowing a quarter of her face. ‘Please come in and sit down.’

A man in a vest and dhoti was sitting with his back to the balcony, retelling, in a mealy-mouthed way, an episode from the Ramayana; people, among them Shyamji and his mother, had gathered around him, listening. How they loved to be instructed, to be charmed by and surrender to, yet again, the wisdom of a tale they’d heard a hundred times since childhood, to have their moral certitudes reconfirmed!

Then, they — these men, some of whom did nothing else for a living but play the cymbals or the tanpura, ghosts who were too much in love with earthly existence to let go of it, but who also had no proper earthly existence; and their wives — they began to sing the arati, the repetitive, sweet, deeply consoling melodic line that made you want to sing it forever. And it seemed to Nirmalya they’d sing it forever — they went on and on, returning to the same phrase. He and Mrs Sengupta had moved up; now, Shyamji and his mother stood before them, their backs to them, as the priest made circles in the air with a lamp, the flame flashing on the air and, barely an instant later, on the eye in swift, disappearing arcs, those circles becoming real only when the moment had passed, when seeing had already turned into remembering. Mrs Sengupta could hear Shyamji’s voice clearly, melodious, high-pitched, uninsistent, like a bird’s; and then it seemed it was only his voice she could hear, and the other voices had become a hum in the background.

It was over; there was anarchy. Children collided with each other and almost knocked down adults in their impatience; Nirmalya and Mrs Sengupta and others (but the mother and son dealt with a courtesy reserved for no one else; everyone, Shyamji included, was obviously made from the same fabric, while they were made from some other) were taken to another room to eat — chickpeas, cauliflower bhaji, paneer, puris, were served on damp plates placed on the long narrow planks of tables.

‘Did you hear Shyamji singing?’ asked Mallika Sengupta. ‘Without tanpura or harmonium or any accompaniment — just the voice: so tuneful!’ ‘Of course,’ said Nirmalya, scooping up some vegetables with the puri. ‘But that’s what you’d expect from Shyamji, wouldn’t you?’ ‘That’s the way I used to sing when I was a child. It came naturally,’ said Mrs Sengupta. ‘You don’t hear that any more these days.’

* * *

‘WELL, THERE WAS that man, going on about Hanuman flying in the sky with the Gandhamadan mountain in one hand and about Sita and Lanka,’ said Pyarelal, standing next to the air conditioner, his kurta-ends fluttering. It was as if he’d been present during that epic moment long before history as we now know it began, and was weary of hearing of such things second-hand. Two days had passed since the grihapravesh ceremony, and he was reminiscing about it; the priest, especially, aroused his ire. He poured tea unhurriedly into a saucer and sipped sweetly from it; he was always uncharacteristically relaxed in the apartment in Thacker Towers, as if it induced in him a state of rumination and stillness. ‘I was hoping he’d stop, but why should he stop? There were Shyam bhaiyya and mataji, sitting before him with such a look of devotion that they seemed to be falling asleep.’ As an afterthought, he cleared his throat and added, like one offering a throwaway insight: ‘The chickpeas were hard.’ And he moved his jaw involuntarily and glumly, as if his teeth still nagged him. His teeth were vulnerable; chewing intractable material could in an instant rob him of the carefree expression that denoted he was in control of the recalcitrant, milling world he moved in every day.

Pyarelal had got a flat out of this; he wanted the flat, but an odd resentment brewed within, because he felt he had no choice but to take the flat. He was emboldened in the huge Thacker Towers apartment with Nirmalya for company; he could express his innate sense of his own grandeur, before sitting down in front of the tablas again, without self-consciousness; and slip, too, into the odd troubledness that came to him from having a piece of property to his name. In the grihapravesh ceremony, he’d had no standing; he’d ushered in Mrs Sengupta and Nirmalya to eat, then got bored of hanging around; being humble and attentive around the idiot hordes of relatives didn’t suit him — he’d slunk into a corner to smoke a beedi.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.