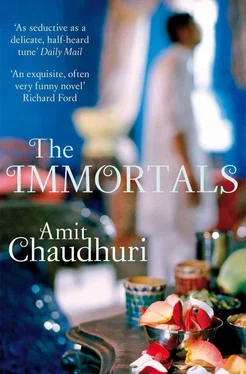

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He seemed on the verge of discovering some new definition; he didn’t know what it was, but it set him apart, a bit cruelly, but also providentially; and it turned his latent lack of self-belief into a bristly superiority he carried about with him always. Even the servants noticed it.

As he began to shed the meanings he’d grown up with, he busily assigned new ones. He fell almost belligerently in love with an idea, to do with an immemorial sense of his country; and music was indispensable to it. The raga contained the land within it — its seasons, its times of day, its birdcall, its clouds and heat — it gave him an ideal, magical sense of the country; it was a fiction he fell in love with. Having subscribed to the fiction, everything else was a corruption or aberration: the Marine Drive, Thacker Towers, the company his father ran, tea at the Taj Mahal hotel — nothing was ‘true’ enough. Looking, soon after sunset, at the sky above La Terrasse and its neighbouring buildings — careful to deny the Marine Drive and the neon advertisements — he thought of raga Shree and how appropriate it was to this moment, only the latest, in history, in numberless such days’ endings — in some place that was both here, and not here, not in Cuffe Parade or Thacker Towers.

A vase catching the light; fresh flowers. Shalini must have come that day to trim the stalks. Teatime; a circle of ladies; one of them, wearing a dress, was English.

Gradually, a thought had begun to niggle in his mind: the ragas had no composer. Where did they come from; and why was no one bothered that the question didn’t have an answer? Indian music had no Bach, no Beethoven — why was that? Instinctively, privately, in a confused way, as he looked evening after evening out of the balcony, the notion of authorship came to him — a difficult thought, which he spent some time grappling with. It was the idea of the author, wasn’t it, that made one see a work of art as something original and originated, and as a piece of property, which gave it value; it was what made it possible to say, ‘It belongs to him,’ or ‘It’s his creation,’ or ‘He’s created a great work.’ And this sense of ownership and origination went into how a race saw itself through its artists. He realised, in a semi-articulate way, with a feeling of despair as well as an incongruous feeling of liberation, that this, though, was not the way to understand Indian music; the fact was a secret that dawned on him and which he had to keep to himself. He discussed it with no one; not with Shyamji, although he’d been tempted once or twice to explore the topic with Pyarelal, but had given up before he’d even started. In the meanwhile, as he read his beloved philosophers and poets, he encountered the celebration of genius everywhere — ‘So-and-so did it first’; ‘So-and-so did it best’ — and he acquiesced in it; but some part of him now, in light of the raga, began to resist it too. Only when rereading Yeats’s poem about Byzantium did he appear to find an acknowledgement in what he read of an art without an author, at least in certain lines and phrases: ‘Those images that yet/ Fresh images beget’ and ‘flames begotten of flame,/. . An agony of flame that cannot singe a sleeve.’ What kind of image could that be, except an image whose author was unknown, and which seemed to have been born of, or authored by, art itself? The lines contained the mystery of what it meant to come into contact with a work of art whose provenance was hidden and, in the end, immaterial. It didn’t matter that you couldn’t put a signature to that ‘image’. Elsewhere, Yeats had called those images ‘Presences. . self-born mockers of man’s enterprise’; Nirmalya thought he grasped now what ‘self-born’ meant — it referred to those immemorial residues of culture that couldn’t be explained or circumscribed by authorship. It was as if they’d come from nowhere, as life and the planets had; and yet they were separate from Nature. Dimly, he saw that, though the raga was a human creation, it was, paradoxically, ‘self-born’.

The painting of the building was three-quarters complete. The men stood on the scaffolding, sometimes they clung to a pole and stretched to the left or to the right, they moved sideways, they squatted casually on a pole, their rags flapping, almost riding nothingness. They never looked through the glass at the tranquillity within; they were too busy, gossiping, shouting, laughing and showing their teeth (he could see the inside of a workman’s mouth, and wondered if he ever spat tobacco from such a great height), all the while at work on that platform. Nirmalya spied on them through the large window. ‘I couldn’t have done it, I couldn’t have done it,’ he told himself, ‘not if my life depended on it.’ One of them slipped, fell; Nirmalya heard about it later. He imagined the young man — they were all young — arms beating helplessly against the emptiness. Work went on.

Nirmalya began to see less of his friends. In the twilight world he’d created, or chanced upon, in the intersection of the raga and nature, his friends were intruders; that world accommodated a great part of the universe — sun, dark, rain, the beating of a pigeon’s wings, a crow’s harsh cry — but it couldn’t accommodate Rajiv Desai, Sanjay Nair, and the others.

Without entirely planning to, Nirmalya abnegated ‘normalcy’; and suffered because of it.

He had moods of withdrawal and renunciation.

‘I want to go to the Himalayas,’ he said, as if he’d given this, and the life he was leading in general, some thought, and decided this was the easiest and most obvious solution. His audience was his mother and Nayana Neogi, the tall bespectacled woman who’d known this family for more than twenty years, and seen Apurva Sengupta transformed from a minor England-returned aspirant into a corporate bigwig with an apartment of seemingly infinite size. She’d reconciled herself to this; her own life with her commercial-artist husband and their pets, and the early thrill of the bohemian manner (she unwaveringly smoked fifteen cigarettes a day, and they lived in the rented ground-floor apartment they’d first occupied twenty-five years ago, and had no property to their name) had become jaded and habit-ridden. Yet habit has the warmth and familiarity of flesh and bone. She was large now, having put on weight in her failed artist’s idleness; too large to wear the hand-woven saris and rudimentary sleeveless cotton blouses with comfort. Instead, she plunged, these days, into a single loose garment that covered her from shoulder to toe and in which she moved about with a sort of freedom. Her old pets died; new ones entered the ground-floor home. A dachshund, a lovely, large-hearted thing, Nirmalya remembered from his childhood, with its low platform of a body and its charred stub of tail; that had, long, long ago, intended to cross the street outside their house and been run over by a car. But there were other, natural deaths, as cats and fox terriers died in old age and senility; as well as a tragic recent one. Nayana had been lying on the beautifully-crafted divan (so plain you might not notice its beauty) with a kitten nestling at her great back; she’d fallen deep asleep in the afternoon, and turned. Waking up to the sound of sparrows, she, who’d not felt a thing, discovered, distraught, that she’d become the kitten’s final darkness and seal. Today, partly with this sorrow, and with the sorrow of her own excessive weight, but buoyant at the change of surroundings, she’d come all the way to the magnificent apartment in Thacker Towers to spend the day with Mallika Sengupta. She was amused to see this boy in the old kurta, whom she’d known since he was a school-going child, standing self-absorbedly before her, the child in him still faintly visible, but also the new, unhappy young man. Ridding it of its cumulus-like appendage of ash, she took a drag on her cigarette; she was oddly moved by his unhappiness.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.