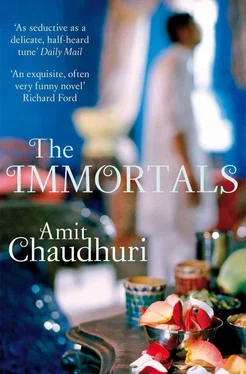

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He went to the balcony and leaned despondently against the bannister. Pigeons on the parapets of the building circled nervously; many of them sat in ranks, curiously unperturbed by one another, waiting for something to happen.

Then, one day that August, it did rain when he was singing. He’d been practising for ten minutes when large drops that had been journeying for miles spattered loudly against the windowpane, and the glass streamed with grey water. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a monsoon raga; it was Bhupali, the verdant, earthly Bhupali, he was very earnestly in the middle of.

‘What a nuisance!’ said Banwari, fingers tapping without interruption, small, anxious eyes upon the window. ‘I forgot to bring my umbrella.’

Banwari, Shyamji’s younger brother, accompanied Nirmalya and Mrs Sengupta on the tabla. He was, at once, composed-looking and nimble, both utterly static and cunningly responsive: like one of those essences or spirits who move everywhere without changing posture, who alter their shape without announcement or without you noticing it. His smile was fixed, almost meaningless, his eyes not half-closed, just small, his hands, always playing, playing, were awake but machine-like, seemingly disconnected from conscious intent. When the song was finished, Banwari’s incarnation altered ever so slightly; it was as if a flesh-and-blood double had taken his place, and immediately decided to savour the air conditioning, the benefits of a physical existence. Conversation ensued; and you noticed his pained civility, bordering sometimes on awkwardness. He still had the awkward air of the young bridegroom who’d lifted the veil off his bride’s face to find an impossibly beautiful woman. Banwari hadn’t recovered from the burden of having a beautiful wife. Everything he did had an air of pained dignity and self-doubt; he felt compromised by his pitch-dark complexion, his teeth. Then, at his wife Neeta’s bidding, he obediently had the two front teeth removed, and replaced by straighter ones: he took the result personally, and was extremely, silently, pleased. Loss or replacement isn’t something you can always exhibit or display; but, at first, he glowed for some reason that people couldn’t quite understand. He never entirely escaped that memory, though; even now, when he permitted himself a joke during the tea break, he covered his mouth with one hand when he smiled, as if it were haunted by the oversized teeth that had been taken out.

The other person who accompanied Nirmalya on the tabla and sometimes on the harmonium was Pyarelal, Shyamji’s brother-in-law. Shyamji disliked Pyarelal thoroughly; but he doled out favours to him for the sake of his sister.

At one point, three years ago, he’d got Pyarelal an appointment in a music school in Jaipur; but he’d come back suddenly, thinner, sporting a new Nehru jacket, darker — something between a returning prodigal son and a visiting dignitary. So Shyamji would not be so easily rid of his brother-in-law. The Jaipur heat (although he’d been born and had grown up there) had been too much for Pyarelal; he couldn’t take it, he said. He’d shown no intentions of leaving Bombay since; the magnetic pull of the city and Shyamji’s family made him hover, hover, like an angel who would not be expelled, in his loose kurta and pyjamas and his pointed slippers.

One of the favours Shyamji bestowed on Pyarelal was letting him accompany Mrs Sengupta and Nirmalya and allowing him to earn sixty rupees per ‘sitting’ for it.

But then Nirmalya began to look forward to his visits. He became attached to the spectacle Pyarelal comprised; punctilious, fussy, qualities, somehow, all the more absurd and acute in him. Pyarelal, in turn, having sensed something with his keen instinct for the unspoken, was effusive in the compliments that Nirmalya so wanted to hear and dreamed were his due:

‘Mark my words, baba will be singing these bandishes like a bird in ten years’ time!’

And the endless and improbable life-history, which he disclosed readily:

‘I used to dance in Raja Man Singh’s court. .’

This sort of thing ordinarily bored Nirmalya; yet Pyarelal, almost an invention, a man not only without status, but without provenance, could never bore him.

‘Man Singh’s court? When was that?’

A deliberate sip of tea, then:

‘I danced before Man Singh when I was four.’

And so Pyarelal had a bit of the stardust of the vanished courtly life around him; and he made it seem entirely believable. He was a jetsam of the old world, part of the coterie of artists that had been disbanded with the palaces, or so he fashioned himself for Nirmalya; not like his younger brother-in-law, who’d been shaped by a city of tuitions, and husbands in the background, and fees. And he sensed that Nirmalya, though he belonged to this particular world, was not in harmony with it, and that his own appeal to the boy lay in his anomalousness; he’d quickly discovered in Nirmalya a powerful nostalgia, a thirst for another time and place almost, that made the boy restless and ill-at-ease. Only Pyarelal noticed this nostalgia; and he’d never seen it in any other young person, certainly not in his three sons or any of the students he played with.

He was a self-styled teacher of kathak dance (though Nirmalya had never seen him teach) who’d picked up, as a child, the various arts of singing, tabla-playing, and harmonium accompaniment. An obscure accident in the past — what it was wasn’t clear; he’d never specified to Nirmalya — had taken away from him the ability to be a performing dancer; he’d now grandly given himself the name of ‘kathak teacher and guru’, although what he was, in spite of the two or three students he reportedly had, was a loyal practice-session man, banging on the tabla while the dancer memorised her routine, twirled round and thumped the floor with her feet till she got it right.

‘Every raga has a roop — a form,’ he’d say with a very adult wistfulness, as if he’d had a vision of a raga once. ‘It has a chehra, a face’ — and here, with the involuntary dancer’s movement, he’d etch the face in the air before him, his own stubbled, hook-nosed face narrow-eyed in concentration — ‘a body. When you sing Yaman properly, for instance, you can see its form. Yaman comes and stands beside you.’

The implication was, of course, that this was not an age in which you saw the raga any more; that for musicians today the raga was an agglomeration of notes, conventions, and rules, to which they brought their subjective passion, their instinct, and different degrees of ability; but to Pyarelal, scratching his chin and imparting his vision to the boy, they were in error — the raga had not only to be played correctly or well ; it had to be courted and pursued.

When Mrs Sengupta found them talking, Pyarelal smiled with a mixture of mischief and satisfaction, as if two lovers had been interrupted by a friend. If Shyamji happened to find them, he started guiltily and got up.

Unlike many male dancers, there was nothing effeminate about Pyarelal: he was short and sturdy. Wrestling had been one of his passions in his youth; he used to spend hours at the akhara, watching indefatigably as men rolled in the sand, or strained, bull-like, their arms locked around each other; bending introspectively, he’d practise holds and positions. ‘Being a man’ was always important to him, as were its fierce attendant concerns, honour and pride.

His face — thin lips, thin moustache, hooked nose, a small wart beneath one eye, the longish hair combed back from his forehead — was hard and bony. Only the occasionally raised left eyebrow, arched and kept dangling briefly in the course of a conversation, bore testimony to the dancer’s art.

‘Kathak’ derives from ‘katha’ or ‘story’; Nirmalya hadn’t realised this before. Words hoarded meaning like treasure; and Nirmalya was at an age when mere etymology brought to sight and lit up an avenue — whose pull was mysterious and irresistible — he hadn’t known had existed. The dancer was not only a virtuoso but a storyteller; this fact was contained in the word ‘kathak’ itself. Sitting on the carpet in the air-conditioned room, the curtains half drawn behind him, Pyarelal showed Nirmalya how Radha would pull the end of the sari before her face to protect herself from prying eyes when she went out into the lanes towards her lover; a motion of the wrist, an avertedness of the eyes, were enough to convey Radha’s vulnerability, her racing heart. Nirmalya, in blue jeans and kurta, for the moment seemingly without occupation, education, or future, leaned against a cupboard door as this fifty-four-year-old man tried, at once, to impress him and to do what was surely legitimate: to reveal to him the elements of his craft. Pyarelal shook one foot slightly to remind him that the bells strung round Radha’s ankle were too loud; that any moment her mother-in-law might awake and discover her liaison. He never got up from the carpet. Sometimes he whispered the song that told the story, which was really a litany of complaints to the divine, blissfully imperturbable lover who was awaiting her, ‘How do you expect me to come on this full-moon night, my ankle-bells ring and threaten to wake up my mother-in-law and sister-in-law, etcetera’, while his nostrils, as he sang, flared imperceptibly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.