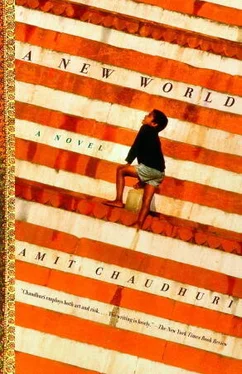

Amit Chaudhuri

A New World

To Rinka;

and our daughter,

Radha

HE HAD COME BACK in April, the aftermath of the lawsuit and court proceedings in two countries still fresh, the voices echoing behind him. But he felt robust.

“Here,” he said to the taxi driver that day in April — it was a Tuesday — when he arrived. His son was staring out of the window, as if a taxi were the most natural place to be in, apparently unaffected by its rusting window-edges and its noise. It was eleven o’clock in the morning; it should be ten o’clock now the previous night in America.

“Stop here,” said Jayojit to the taxi driver. “Kitna hua?” he asked.

Vikram — that was his son’s name, his maternal grandfather’s choice — said, “Are we here, baba?”

Though they spoke to each other in English, both Jayojit and his wife (ex-wife now? but she had still not married the man she was living with) had decided to retain, as far as their son was concerned, the Bengali appellations for mother and father: “ma” and “baba.” Ironical, thought Jayojit — he thought about these questions more and more these days; indeed, he could often hear himself thinking — that we did not think to teach him, at least in practice, the other things that surround those words in our culture. He himself had learnt those meanings from the lives of his parents. It was curious how often he returned to his childhood and growing up these days, involuntarily, to their apparently random and natural sequence.

“Seventy-five rupees,” said the driver, turning his head and smiling; the man hadn’t shaved for a few days. It was as if the taxi were his home and he had long not stepped out of it.

“Seventy-five rupees,” repeated Jayojit with a chuckle, while the driver smiled with a strange but recognizable demureness; the coyness of a struggler taking something extra from a person he considers well-to-do. Jayojit knew, from glancing at the numbers that had appeared on the meter, that he was paying more than he was supposed to, but he silently rummaged the new rupee notes in his wallet; he had changed fifty dollars at the airport.

“Yes, Bonny, we’re here,” he proclaimed cheerfully to his son; Bonny was his pet name, given him by Jayojit’s mother, a strange Western affectation from the old days, to call children names like these — though his mother was not westernized. The boy, his pale face red with the heat, with one or two darker streaks — evidence of the journey, of plane seats, uncomfortable positions, attempts to sleep — on his cheeks, was looking quietly at the gates. A sound, oddly lazy but determined, of a plank of wood being hit again and again, could be heard. The watchman at the gates of the multi-storeyed building and the indolent, shabby chauffeurs of the private cars, lounging in the shade, their backs leaning against their cars’ bonnets, seemed to be intent on watching the occupants of the taxi and listening to that sound.

“E lo,” said Jayojit, handing the driver the money, who took it and began to count the notes. Experimentally pulling the lever that opened the door, he said to his son, “Bonny, that’s the way to do it.”

They had come with one heavy suitcase and a large shoulder bag slung around Jayojit’s neck; in one hand he was carrying an Apple laptop and a one-litre bottle of Chivas Regal in a duty-free bag. The boy was wearing a bright-blue t-shirt and shorts, and on his back there was a kind of rucksack; he walked with the mournful loping air of a miniature expeditioner. The two or three part-time maidservants who always sat by the entrance steps looked at the two arrivers casually; it was as if they were used to the sight of huge itineraries, arrivals, and departures, and it no longer disturbed the monotony and fixedness of their lives. A faint smell of stale clothes and hair-oil came from them. Jayojit was a big man, five feet eleven, and fair-complexioned and still handsome in a bullish way; he was wearing a red t-shirt and off-white trousers on which the creases showed, and two Bangladesh Biman boarding cards stuck out from his shirt pocket.

The flat was on the fourth floor, number 14; a long corridor led to it, and then became a kind of verandah before it and its neighbouring flat. The nameplate on the door said “Ananda Chatterjee.” He pressed the doorbell, which was really a buzzer with a prolonged droning sound which he associated with an immemorial middle-class constrictedness; and his son stood facing the door, staring at the one-inch ledge at the bottom. It was Jayojit’s mother who opened the door; immediately, upon opening it, her face, a rainbow of late morning light and shadows, of tiredness and alacrity, lit up with a smile, and she said: “You’ve come, Joy!”

“Yes, ma,” he said jovially, and bent his big body to touch, in one of the awkward but anachronistic gestures that defined this family, her feet.

“You’ve put on weight, have you,” she said. “There, let it be.” Then looking at Vikram she smiled, widening her mouth, so that her teeth showed, and said: “Esho shona,” and then, remembering he might want her to speak in English, “Come to thamma.” For the first time Vikram smiled.

Admiral Chatterjee was sitting inside on the sofa — a heart condition and diabetes had made him slow; but he was a big man too. He looked like a sailor, his longish grey hair and beard suggesting voyages, deck-parties, and a sea breeze; a painting by a minor artist, bought many years ago for five hundred rupees, hung behind him.

“How was the trip, Joy?” he boomed as he got to his feet. “All right?”

They — Jayojit and his father — communicated, except for a few words and sentences, in English, establishing a rapport, a bluff friendship, which excluded the tenderness of the mother-son relationship — the latter finding expression in the mother’s homely, slightly irritating Bengali, and talk centred round questions such as whether her son was hungry, or whether he had had a bath.

“Bloody taxi driver took extra money from me,” said Jayojit with a large smile, and then bent to touch his father’s feet. “Pranam karo, Bonny,” he said. The boy, who had been slipping off his rucksack so he might put it on a chair, interrupted himself, turned to walk gravely but obediently, with a light-footed sneaker-tread, towards his grandfather, to touch his feet.

“Let it be, let it be, dadu,” said the grandfather, who always seemed a little uncomfortable with others, whatever the situation. To his wife he said, “Ruby, give the child something to eat!”

It was not easy to be intimate or relaxed with the Admiral. He was one of those men who, after independence, had inherited the colonial’s authority and position, his club cuisine and table manners, his board meetings and discipline; all along he had bullied his wife for not being as much a mem-sahib as he was a sahib. She had adored and feared him, of course, and paled beside him. Only before two things had he become strangely Bengali and native. The first was his in-laws; in those days when his wife and he still quarrelled and his in-laws were alive, his wife, crying softly, would pack her things and go away for a week to her parents’ house; and he would be left dumbstruck, unable to say anything. The second was his grandson — Vikram; Bonny. He could not reconcile himself to the fact that the boy had to tag along part of the year with Jayojit, and then go back to his mother, who was living elsewhere on the vast American map, with someone else. He could not comprehend the loneliness of the child, or why the loneliness needed to exist. Yet, in spite of this, and in spite of the fact that the old India had changed, and he himself had grown somewhat decrepit, the official air still hung around him, like a presentiment.

Читать дальше