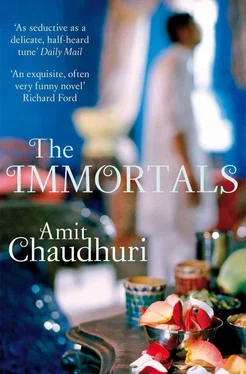

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When Nirmalya asked Pyarelal to write down for him one of the many songs he had recited or sung for him in the last few months, he discovered that the older man was barely literate. The Devanagari script was largely uncharted terrain, a country Pyarelal felt no pressing need to visit, and which he’d avoided visiting for the greater part of his life with no excessive sense of loss. For Nirmalya’s sake, though, he made an attempt, and set down four lines in the exercise book that was Nirmalya’s songbook in a faint and almost illegible handwriting. He smiled, as if asking indulgence for a disability (not a serious or harmful one, but a disability nonetheless) for which there was no immediate cure, and which it was in slightly bad taste to discuss.

However much he hid it from the boy, and however much his memories spoke of a spontaneous joy in life, Pyarelal was marked by a sense of inadequacy. All his memories were, strangely, from before his marriage, his restless loiterings between Rajasthan and Dehradun (where he’d lived for four years) and then Bombay, where he’d deliberately inserted himself into Ram Lal’s life and then, as Shyamji would have it, got himself married to Ram Lal’s daughter. Pyarelal’s memories dried up after this; life seemed to have become more real, less surprising, and, somehow, less life-like. He compensated for that sense of inadequacy, his sense of the lack of the respect due to him, in his own way. It was common knowledge that he got drunk in the evenings; and, since everything in a family becomes familiar and then comic, especially to children, this fact became a joke, to Shyamji’s children in particular, who, since they were small, had both lovingly and mockingly called him ‘Puaji’, a lisping abbreviation at first, unable as they were then to pronounce ‘Pyarelalji’, and then just an appellation, like ‘uncle’ or ‘kaka’. People seldom mentioned the unfortunate closeness of ‘Puaji’ to ‘paji’, or ‘wicked’, but come evening, and the children in the neighbouring house knew that Puaji became garrulous and beat up Tara, their aunt. In his home, he was unassailable. Who was he? He was Ram Lal’s daughter’s lord and master, after all. Shyamji didn’t, wouldn’t, intervene; he was scrupulous about washing his hands of this unpleasantness, as he was about many others. What Pyarelal and his family did in the confines of their four walls was their business.

* * *

‘WHAT DO YOU talk to him about, baba?’ asked Shyamji sadly. He looked calm, but his resentment was essentially stubborn, unappeasable.

Pyarelal had just made an exit, scraping, bowing, saying ‘Yes, bhaiyya, no, bhaiyya, bilkul, bhaiyya’ to Shyamji.

Nirmalya was at a loss for words.

‘He’s a master of drama,’ said Shyamji, before Nirmalya could answer his question.

Pyarelal had his own method of exacting, quite ingenuously, revenge on Shyamji; he did it by extolling his father-in-law, the dead Ram Lal.

‘The first night of the conference in Calcutta, Bade Ghulam Ali sang Bihag,’ he recalled with a half-smile, as if the ustad’s voice were audible to him. ‘And then there was Bihag and only Bihag in the air. The second night Panditji’ — that was how he referred to Ram Lal — ‘sang Malkauns. And then there was Malkauns and only Malkauns!’

The son-in-law, who’d arrived out of nowhere and inserted himself into Ram Lal’s affections, recounting the dead.

‘But what about Shyamji?’ asked Nirmalya, his heart brimming with feeling for his often-absent teacher. ‘He sings wonderfully too, doesn’t he?’

‘He sings very well, but he’s only four annas compared to Panditji,’ said Pyarelal with a ruminative laugh. Four annas; a mere twenty-five per cent. And since it was the father who was being praised, even Banwari, the younger son, had to nod solemnly when remarks like these were made. Not only Banwari — a swift shadow passed over Shyamji’s face when words like ‘But no one can sing these songs like Panditji’ were said, and he’d nod in defeat and add, ‘He’s right, baba, you did not hear my father.’ It was as if, at such moments, logic deserted him, and the insurmountability of life revealed itself. And the sixteen-year-old would be filled with pity, and at the same time convinced the claim was a lie; that people create lies about the dead to torment the best of the living.

The best of the living: although Nirmalya was convinced his teacher was among the ‘best’, he was disappointed by Shyamji’s pursuit of the ‘light’ forms, his pursuit of material well-being. An artist must devote himself to the highest expressions of his art and reject success; he was going to be seventeen, and these ideas had come to him from books he’d read recently, but he felt he’d always known them and that they were true for all time. He put it to Shyamji plainly:

‘Shyamji, why don’t you sing classical more often? Why don’t you sing fewer ghazals and sing more at classical concerts?’ Shyamji was always unimpeachably polite. He now turned to study the Managing Director’s son’s face with curiosity, as if he were reminded again of the boy’s naivety.

‘Baba,’ he said (his tone was patient), ‘let me establish myself so that I don’t have to think of money any more. Then I can devote myself completely to art. You can’t sing classical on an empty stomach.’

Nirmalya had heard a version of this argument in college: that you must first satisfy your physical needs, of food, shelter, clothing, before you can satisfy your psychological ones — like culture. He wasn’t persuaded by his guru’s words. How did you know when you arrived at that point, when you were safe enough to turn exclusively and fearlessly to the arts? How, and for when, did you set the cut-off date? Nirmalya had never known want; and so he couldn’t understand those who said, or implied, they couldn’t do without what they already had.

* * *

HE WENT TO the balcony, considered the view: much-praised, much-prized — more valuable than any of the artefacts inside, it raised, in its daily, innocent rehearsal of daylight and sunset, the price of the apartment to what it was. La Terrasse, white and wide, was in the distance; as was the long strip of beach, like a thin ore of gold, tapering towards the Governor’s house.

When you looked straight down from the balcony at dusk, you could see the outlines of people on the edge of the land. Thacker Towers had begun to be repainted before the monsoons, and now work continued in bursts between rainy days. Bamboo scaffolding had been erected around the buildings: and sometimes, when Nirmalya was reading or listening to music in his room, he’d see a man, or men, appear just beyond the balcony, careless as sailors on the top of a mast, seemingly uninterested in his presence.

Word circulated that Mr Thacker hadn’t provided them with toilets — or maybe it hadn’t occurred to him that they’d need toilets. It was these men and their families who gathered below at dusk on the edge of land in the shadow of Thacker Towers.

Almost seventeen, he was leaving his father’s world behind — the sitting room behind him, its paintings, ashtrays, curios, vases, the study at the far end with its bound volumes, the dining room with the thick oval glass table, the four bedrooms. Since moving to Thacker Towers, he’d stopped feeling at home. Only the flies, which, in spite of the wire gauze, kept returning, amused him; he eyed the doomed one beadily and killed it heartlessly.

When he was a child, home was escape — from the terrifying terrain of nursery and school, of shiny alphabet charts with their motionless constellation of cats, balls, and vans; of a physical education of running and falling, and singing lessons when you stood like soldiers; and glancing every few minutes at the great hands on the white clock-face. But now, his father having assumed the mantle of the Managing Directorship, this flat in Thacker Towers, with all its furniture — the Himalayan peak of his father’s career and probably Nirmalya’s own material life — was strangely arid to come back to, like a place that could never be properly inhabited, lit by the sun at different points in the day, and by the electric lights heavy with crystals in the evening.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.