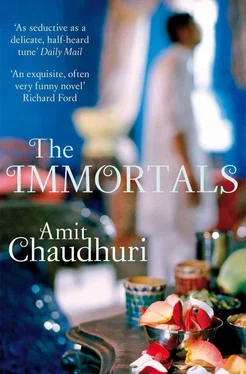

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And yet how wonderful it was to be in his guru’s house, the electric bulbs making the room bright, a room in which visitors were welcomed, but in which the divan where they sat, lightly covered with a sheet, obviously became someone’s bed at night. Mrs Sengupta did most of the talking; Nirmalya was largely silent, as he used to be when he accompanied his mother to the houses of acquaintances as a child; he held Shyamji in too high a regard to ever have a comfortable conversation with him. Besides, what would they talk about? They couldn’t discuss music, because it was not discussable; it was a set of rules and commands that had to be passed on and picked up almost unthinkingly. In fact, it wasn’t certain Shyamji ever thought about the kind of things that Nirmalya considered the province of thought ; it seemed that his immediate future and that of his children, and, in that context, the business of proper conduct and what was admissible were what exercised Shyamji in his daily life. Nirmalya didn’t consider this ‘thinking’; his own daily life involved an agonising — punctuated by blank phases of stupefaction — over the history that, from the beginning of time, had gone into forming the moment that he now, in 1981, found himself uneasily in. Shyamji would, in all probability, have met these ruminations with incomprehension. The question, then, of having a conversation with Shyamji didn’t arise — where would it lead? Nirmalya was happy to be there, to sit and listen, as he often did when his mother talked, while two smoking cups of tea, brown with milk, were placed before them, and he, from time to time, as he sat there, became lost in the difficult, tenuous weave of his own speculations.

The second time Mrs Sengupta went to Shyamji’s house, she found a self-conscious, dark woman, somewhat younger than her, sitting on the divan.

‘Didi, this is Ashaji,’ said Shyamji, with an added carefulness and civility. ‘She is singing two songs in the film: we are very lucky.’

Mrs Sengupta looked at her again, this woman whose songs were played every day on the radio, and who, with her elder sister, reigned in a dual tyranny over the Hindi film music world. The face was benign, but mask-like; she seemed slightly ill at ease.

‘My son is very fond of your singing,’ said Mrs Sengupta as she sat down. Asha’s face brightened imperceptibly, but the mask-like composure didn’t change.

‘You should listen to didi some day,’ said Shyamji, assured, mellifluous. ‘She has a very beautiful voice.’

‘Oh I can tell,’ said Asha, smiling faintly. ‘Her speaking voice itself is musical to the ear.’ Her speaking voice was a degree louder than a hoarse whisper; the words were spoken with the slow deliberateness of a child.

These words came back to Mallika Sengupta the next day; yes, she was pleased with them, but she dismissed them; it was beneath her to accept such crumbs of appreciation from this woman, who’d appeared to her in the incarnation of an ordinary working person in a plain printed sari. There was no getting round it; she lived in a world wholly separate from Asha’s, married happily to a successful man, moving about in sparkling, if occasionally vacuous, circles. But she wondered whether it was accident or destiny or her own hidden desire that had made her what she was. She’d never wanted to be Asha; yet what was it about her own talent that made it meaningless without the happiness she had, and also always made the happiness incomplete?

* * *

SHYAMJI’S STOCK had gone up steadily in the last three years: he decided to leave this small rented flat in which he’d lived for decades. Besides, families were growing larger; in neighbouring flats in the row of chawls, Banwari and Pyarelal lived with their wives and children. ‘Beta, Shyam,’ said his mother, small but zealous in her widow’s white sari, ‘you must do something, the children are growing up, there is no room any more.’

So they left King’s Circle; it was almost a wrench, to leave the noise of the gurdwara and the congestion. The task of acquiring the new properties in which the families would now be located, of dividing the money they’d get from their old landlord on vacating their flats in the chawl and using it for this purpose, of applying for loans — all this was left to Shyamji. Pyarelal, barely literate, kept himself in the background (even his withdrawals were dramatic and meant to draw attention), restricting himself to nodding or shaking his head like a deaf-mute when a response was required. On the whole, Shyamji ignored him; his eyes glazed over whenever Pyarelal drifted into the vicinity; but he went about his business stoically, of providing his brother-in-law and his family, besides himself and his brother, with a place to live. Banwari was no help either; he lacked confidence in himself. He continued, silent, decorous, with his old routine, of playing the tabla at various people’s houses, practising, quite deliberately, an abnegation of his own from his brother’s search, as if there were no change in his life.

‘He wants me to be his guarantor,’ said Mr Sengupta to his wife at night. He cleared his throat. The lights had been turned off; they were lying on the large bed, talking to each other. The Tibetan rug by the side of the bed, the carpet between the raised wooden floor that surrounded the bed and the way to the cupboards and the bathroom, the swirling wallpaper behind their heads, the faint moth-like glow of the ceiling which they stared at from the pillow, a deeply soothing sight in the day’s last wakefulness — all this, as one of them flicked the switch, vanished and was reduced to an aftermath where they were nowhere. Their eyes were open, and they lay wondering; the day’s bright magic returned, and its niggling, unresolved questions, loosed from the visible world, hovering like remembered images as their eyes grew used to the dark.

‘Guarantor. . for what?’

‘He said to me yesterday — he was very hesitant,’ here Mr Sengupta switched to his familiar clumsy version of Hindi, ‘“Sengupta saab, I’m applying for a loan to buy the flats. If you are my guarantor, Sengupta saab. . Anyway, I’ll return the bank the money in two or three years.” That’s what he said.’

They were silent against the equanimous, life-giving, sempiternal background of air conditioning. They weren’t entirely happy with Shyamji; he was quick to demand and borrow money from Apurva Sengupta, and to make easy promises to his wife. But he hardly made good those promises; Mallika Sengupta’s career as a singer was there — exactly where it had been ten years ago; Laxmi Ratan Shukla was no closer to recording her first disc than when they’d first met him; she still sang, with the purposelessness and dedication of something between a nun and a housewife who’s in exile in her own household, the bhajans Shyamji gave her, but mainly at home. ‘Didi, that voice can make you famous in the world,’ Shyamji said; but she doubted, during moments of hiatus such as this one, when she was lying on her back, eyes closed, listening, her thoughts everywhere, whether he meant anything he said.

Apurva Sengupta confessed after a few seconds:

‘I’ve decided to sign the form.’

‘He thinks’, Mrs Sengupta warned her faintly visible husband, ‘that we have a lot of money. He sees our lifestyle, and thinks we’re rich. God forbid that anything should go wrong after he buys the flats. . You know you have no money.’ It was the incredible story they kept rehearsing to themselves; that executives like Apurva Sengupta had the perks — the lavish apartment, the Mercedes-Benz, the servants — but, as they saw it and felt acutely, no wealth, no ballast, no substantial material possession, especially in comparison to the people they called, in the simple but expressive language of the age, ‘businessmen’. It wasn’t a story that either convinced or appealed to Shyamji.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.