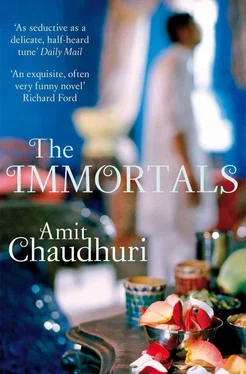

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

No one took much note of Pyarelal. But Nirmalya actually listened to what he said, and took a perversely different view of him. He was in the midst of a discovery when it came to Pyarelal; he was, in a sense, inventing the older man. Later, he’d never be able to recapture the first flush of this excitement, which had aggrandised Pyarelal to him and made him unique, and would see only the mortal, damaged, cringing man. Pyarelal, too, seemed to sense at times that he was caught up in a web of Nirmalya’s making, and was unable to, in fact content not to, extricate himself from it; although, once or twice, without even being aware of it, he’d glanced at the boy with a look of incomprehension and almost of sadness, as if some buried part of him wondered how long the spell would last. ‘Ma,’ Nirmalya said to Mrs Sengupta, ‘he may be hardly able to read and write, but he has what in an educated person would be called a “critical mind”.’ For Pyarelal took nothing as received wisdom, not even the saint-poets. ‘Tulsi, Kabir — they’re wonderful,’ he’d said. ‘But Meera? Much of the time there’s no merit in what she writes. “Pag ghungru bandh Meera nachi re” — “Bells strung round her feet, Meera dances” — is that a line worth speaking of?’ He looked straight at Nirmalya, as if he’d made an unpleasant remark about Meera’s anatomy but was confident nevertheless that what he’d said was fair. Nirmalya was taken aback; for no one he knew thought of whether Meera’s lines were good or bad; they celebrated her mythology, the tale her songs narrated, of how she left the Rana, the king she’d been married to, and his palace for the love of Krishna; how, again and again, the Rana tried to poison and kill her; how each time, magically, his attempts were thwarted. All this was as familiar to Nirmalya as a story in a comic book. But now, as Pyarelal stared at him, the famous line ‘Pag ghungru bandh Meera nachi re’ began to sound dead to Nirmalya’s ear; Pyarelal had killed it. ‘Of course, she has some good lines,’ said Pyarelal, his mood changing into one at once imperious and democratic. ‘Hari, vanquish the world’s sorrow,/ Rescue the drowning elephant,/ Lengthen the garment that covers.’ Nirmalya understood the allusions compressed in the lines much later — about the elephant, dragged into the water by the crocodile, being rescued by Krishna when it invoked his name; and of how Krishna infinitely extended the yard of cloth that formed Draupadi’s sari as Dushasana tried to strip her of it. Meera, in this song, wasn’t calling upon the Krishna who was her secret lover, as she did usually, but to Krishna, the vanquisher of the world’s sorrows — ‘jan ke bheer’ — and, though Nirmalya was yet to comprehend all this, the music of the words sounded to him distinct from the indisputable flatness of the other line. He stole a glance at Pyarelal. Could it be because this man could barely write that the sounds of words were more audible to him? A theory began to take shape inside his head.

‘Not being able to read and write makes life difficult,’ admitted Pyarelal sadly, one hand on the harmonium.

‘All those forms. .’ he said, using the English word and mournfully turning it into farms . ‘All those farms to fill. .’ For the semi-literate musician in Bombay, hemmed in and kept in his place by thickets of bureaucracy, life was a conspiracy of forms.

But what living in the tiny flat in the chawl in King’s Circle for fifteen years had done to him was evident sometimes. Before he sat to play the harmonium with Nirmalya in the boy’s small, introspective, neat bedroom, Pyarelal would turn and primly close the bathroom door. If it were ajar behind him, he’d be unable to concentrate on the music; he’d get up in exasperation and shut it. ‘Why is this open?’ The tiles glowed; they gave off a fairy-tale emanation. The basin was encircled by granite and marble; the instruments of washing and defecation were guarded and polished daily by a jamadar like a museum’s treasure. Nirmalya wondered why the half-open bathroom door so unsettled poor Pyarelal. It was only after visiting the chawl in King’s Circle, and learning more about Pyarelal’s and Shyamji’s and Banwari’s lives, that he understood the stench of a shared toilet, a stench which, given an inch, would insinuate itself into and quietly colonise the house. Pyarelal sniffed the air; he smelled what wasn’t there. It was the smell of the toilet in King’s Circle that agitated him.

* * *

SHYAMJI FELL ILL. He’d felt a sudden pressure on his chest, and rubbed it unhappily with one hand; he’d been taken to a nursing home. It was a mild heart attack.

‘However did it happen?’ asked Apurva Sengupta, phoning his wife in the middle of work. He sounded impatient, as if the knot in his tie felt tight, or his secretary had gestured to him about an appointment; it was three o’clock, a quiet but demanding hour, in which the chief executive, suddenly alone after lunch, has to collect the day around him. ‘Is he all right?’

Shyamji was only forty-three. He was slightly overweight — Nirmalya had seen him changing his kurta before a programme, the rounded, dark body beneath the vest, the tender, secretive folds of flesh, the brahmin’s thread tucked inside: his condition was aggravated by diabetes.

‘You must stop him eating sweets,’ Mallika Sengupta said to Sumati. That irresistible, and, to Mrs Sengupta, inexplicable urge that people from this particular world had towards jalebis and milk. ‘If he, a grown man, can’t control himself, you, as his wife, must control him.’

‘Didi, you know that our Shyamji is like the Shyam after whom he was named,’ said Sumati, with a smile that was lit at once by indulgence and ecstasy. ‘He’ll steal into the kitchen and eat what he pleases — no one can stop him.’

There was an idiotic poetry to Sumati’s words that infuriated Mallika Sengupta; she recalled, for an instant, the child Krishna stealing into his mother’s kitchen to satisfy his truant love of buttermilk. But that Shyam was a god, a diverting figment of someone’s imagination, she thought; your husband has just had a heart attack. Sumati was placated and insulated from anxiety by mythology — the mythology of her religion had entered into, and become inseparable from, the mythology of her husband: no real harm could come to him.

The rich of Bombay came to his bedside in the nursing home as he recovered, his head propped against two pillows, a flower vase, a tumbler, and a bottle of water on the table next to him. ‘Aiye, aiye,’ he said, as if he were welcoming guests to his abode, his gaze incredibly calm. He was fatigued; but it was reassuring, this arrival of the affluent. Outside, ‘sisters’, figments in white, circulated purposefully in the corridor, sending in, now and again, proprietorial glances through the doorway. At different times, the visitors: Priya Gill and her father, indomitable and inspiring in his Sikh’s turban; Raj Khemkar — his father was no longer a minister, but Raj still carried with him the ironical confidence of a minister’s son; Mrs Jaitley, whose husband had been recently promoted to General Manager of Air India — all these, and others like them, brought with them, unthinkingly, the assurance of the everyday and of continuity as they sat kindly by the bed, confirming the solace of the birds and the hopping and buzzing insects outside the window on Shyamji’s left.

And the famous; Asha, who said in a hoarse voice (you were always nonplussed, listening to that voice, that it had sung, full-throated, those melodies): ‘How is he?’ and, putting a bangled hand to his forehead: ‘You have no fever.’

One of the people missing from the bedside was the bearded Hanuman Rao, the Congressman who wore nothing but white. But no one mentioned Hanuman Rao. The film Naya Rasta Nayi Asha — a new road, new hope — had been made, but it suddenly seemed unlikely it would ever be released: that the new road would be taken, the hope materialise. Hanuman Rao had fallen out of favour with the powers-that-be in the Congress, puny men in scheming huddles who resented his largeness, metaphorical and physical; an old but niggling case, to do with his role in his constituency during the Emergency, had been brought back into daylight by a member of the Opposition; the Congress had neglected, carelessly, to bail him out — some said the return of the case was instigated by some malevolent force in the Congress itself. Hanuman Rao hadn’t been arrested; but his assets were frozen, and the film, alas, was one of those assets. Naya Rasta Nayi Asha , soundtrack and all, had been sucked forever into the tunnel of lost prospects; and with it had gone, also, the thousands of rupees that Shyamji had put into it, in the glory and unassailability of having turned, at last, into both ‘music director’ and ‘playback singer’.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.