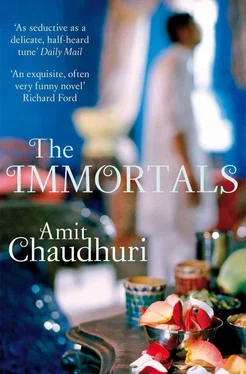

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He emerged, two months later, from the arrivals area at Sahar International airport, blinking in surprise at the sunlight, steering sadly, this man who could neither drive nor cycle, a worn, stuffed burgundy bag with buckles upon a trolley. In the midst of the large crowd, standing in the sun behind flimsy railings and watching the spectacle of passengers coming out one by one and walking down the catwalk before the arrivals exit — in the midst of all this his family was waiting, and broke rank imperceptibly on seeing him; he touched mataji’s feet, she blessed him with a detached, immovable satisfaction at something having come full circle, others came forward awkwardly to lightly touch the returning man’s toes. The first thing his sister Tara asked, with a sardonic lopsided grin, was:

‘What did you bring for me, bhaiyya?’

For some reason, he was disgusted by the question. His eyes, which had had little sleep, stared back at the bright sunlight of the city. Was it being married to Pyarelal that had turned Tara into — a beggar? It wasn’t unusual, he thought (walking, like one already beginning to reluctantly embrace the old habitat, towards the line of quarrelling black and yellow Fiats), for wives to take on the characteristics of their husbands. She was no longer little Tara, his sister and Ram Lal’s daughter; she was Pyarelal’s partner and comrade. But, at a glance, it was true of all of them waiting there for him — they weren’t waiting to receive him, they’d been preparing these months to swallow him up; wanting things from him, wanting things, wanting things. It was hot, but he froze inside; he had nothing of himself to give.

His health had improved noticeably after the two summer months in London; he’d lost weight, and felt younger and the better for it. He still hadn’t abandoned his new clothes; he came to visit the Senguptas wearing shirt, trousers, and strapped sandals. It was like meeting a man who’d returned from the past, with a new alias and a new future. Beneath the clothes, of course, he was the same man; Nirmalya thought of the quaint English phrase, ‘in the pink of health’, and thought how apposite it was to Shyamji at this moment, incongrous though it was to his complexion.

‘It is a good country,’ said Shyamji moodily. ‘I would be happy living there. I was thinking, maybe I should move there.’

Mallika Sengupta smiled, a little alarmed, although she perfectly understood the sentiment — the sense of possibility, which had come a bit belatedly to him, which suddenly makes things plain; she dismissed the possibility herself, because Shyamji emigrating would leave her without a teacher. But the words disconcerted Nirmalya; all his ideas that were derived from reading books on philosophy and English poetry told him the artist must belong to and practise his art in his milieu. How could Shyamji think of giving up his country so easily? Besides, being a Hindustani classical musician, Shyamji’s art was intimately connected to these seasons, this light, an intimacy that Nirmalya had not too long ago discovered for himself. After this discovery, which to him had the force almost of a moral revelation, he couldn’t understand Shyamji’s new-found rootlessness, or the mildly challenging look on his face as he said those words.

* * *

BUT SHYAMJI didn’t leave the country — at least, not permanently. In the following year, he made two more trips to England; his life, and his lifestyle, improved, as if one of those tiny, mute goddesses, whose vermilion-smeared pictures he bowed his head before, had impulsively decided to shower him with bric-a-brac and useful things. So he acquired a second-hand Fiat and employed a young driver to make that long journey from Borivli to various parts of the city.

‘Whatever Hari wishes,’ he’d say, glancing heavenward at the clouds from which the second-hand car had descended.

He arrived at Thacker Towers in it; it saved him the travail of trains and taxis. He was still not a ‘bada saab’; he couldn’t afford an upmarket ‘vehicle’; but he was proud of the turn in his fate that had brought him his own ‘vehicle’.

Very apologetically, he raised his tuition fees; ‘What can I do, didi?’ he said, with a pained but firm expression, fairly comfortable that what most of them gave him was a fraction of what they spent every day on a decoration, a painting, or a sari.

After his third trip abroad, he had cleared most of his outstanding debts. And he had enough money left over to sell his own flat in Borivli, and, with that money and some of what he’d recently earned singing for enthusiastic, cushion-propped, sprawling drawing-room audiences in Frognall Lane (how noisy and drink-and-peanut infested that quiet house became during soirees!) and performing in other places in London, he bought a two-bedroom apartment in Versova, facing the sea. This building complex, ventilated and its windows shaken from time to time by sea breezes, was appropriately called Sagar Apartments; it had been built for traders who’d acquired social pretensions and a bit of extra, unaccounted-for money and wanted not to be left out of the property boom; living for years, even generations, next to shops and godowns in humid rooms, they’d developed a longing for the sea. The porch and the corridors leading to the lift were laid with marble, the one stone that, in the city, had the ability to confer prestige indiscriminately upon a habitation. When Shyamji moved here, the building was brand new, and the white surface was still smudged by the footprints of labourers; but his eyes were temporarily, pleasantly, engulfed by that whiteness. With him moved to that smart two-bedroom flat mataji, the mother, and his wife, and his two unmarried daughters and son.

‘Papa,’ said Sanjay, Shyamji’s fifteen-year-old son. He spoke softly, but in an abstracted insistent sing-song. ‘Papa, Motilal mamu’s son Kailash was saying that to learn music arrangement properly you have to have a keyboard.’

‘Hm? Who said?’ asked Shyamji, tugged against his will from the wideness of a reverie into the constricted space of this non sequitur. He was full of these absent moments, when he seemed to be thinking neither of his family nor his students.

‘Kailash,’ repeated his son determinedly.

‘Bewkoof hai,’ said Shyamji swiftly, serenely. ‘He’s an idiot.’

But Sumati, Shyamji’s wife, who was within earshot, smilingly and defiantly took up cudgels on this Kailash’s and her son’s behalf: ‘After all, learning the keyboard now will mean that our Sanjay will be able to become a music arranger by the time he’s eighteen, God willing’ — she’d had a vision of that moment in the future, it was an image that had a certain power over her — ‘and’ — here her prescience was lit by tenderness — ‘see how beautifully he already plays the guitar.’

All these Western instruments. . They were glamorous because they’d arrived, intact, after a long journey; once here, they could merge intrepidly into the texture of almost any musical background — it was not as if Shyamji wasn’t won over by their virtues and innate youthful qualities himself. A man who could play a Western instrument would always have a livelihood in today’s world: so it seemed to the old music families. The tanpura, with its four strings, hadn’t lost its magic, but it became more and more difficult to make time for it; still, its sound shocked you every time you heard it — like a god humming to himself, its vibrations difficult to describe or report on, the solipsism of the heavens.

A slim white synthesiser with an apparently interminable row of white and black keys arrived in that room; Sanjay began to toy with it at once — the tinselly cascades of sound introduced a new and slightly embarrassing atmosphere to the small apartment, filmi , but upbeat and busy with possibility.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.