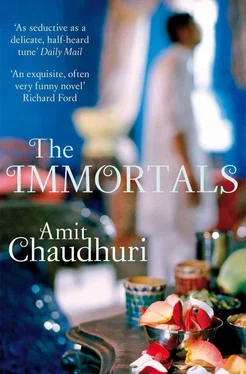

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For two days, a series of chords, seemingly arbitrary, but executed in a variety of keys in quick succession, took over life in the little drawing room. People began, eventually, to ignore the boy; from time to time an awareness registered on Shyamji’s face in a faint smile, as if his son were a child again, and kept encroaching obstreperously, in his single-mindedness, upon his own concerns — for this is what it had been like when Sanjay could neither walk nor talk, but possessed, in his play, the same glassy-eyed, silent, dogmatic zeal.

The synthesiser dazzled Sanjay, starting from the special excitement of the name — Yamaha; and, as had been promised, there seemed to be no sound he couldn’t extract from it. It was as if an orchestra, minus the heavy, inconvenient corporeality of human beings, lay latent inside it, constantly changing shape, obedient to his fingertips. It was portable; like a wand, he carried it from location to location, room to room.

When Shyamji and Sumati had exchanged garlands when they were eighteen, their respective, impeccable musical lineages had been taken into account to create a gene for the future, a gene which Sanjay, ruffling his hair with one hand, and running the other across the keyboard, represented. But such calculations don’t allow for the fact that propensities suppressed in one generation might find freer rein in another, that the gene is self-perpetuating but also self-divided, that it contains within it its own destruction and mutation.

‘Music is leaving the house of the ustads, the maestros,’ an ageing and somewhat pompous singer, a friend of Ram Lal’s, had said not long ago to Shyamji, bitterly, as if the younger man were in some way responsible. Shyamji had nodded solemnly, placatingly, in all sincerity; at that moment, he’d thought it safest to be in complete agreement with the octogenarian. But, at this point in his life, he didn’t really care — he didn’t care exactly where music was located. And he had no pressing worries about whether the splendid but little-known inheritance his father had created would peter out; true, Sanjay hadn’t been patient enough to acquaint himself with all the beautiful, difficult compositions, and Shyamji too had become busy of late — but there was time; he was forty-four, Sanjay was sixteen; it would be done, though, of course, it would require diligence and hard work! The gharana was the least of his worries. He cared — he wanted to ensure — that life expanded for him, his children, his children’s children, and that when opportunities came or returned — as they seemed to be doing suddenly — he made full and intelligent use of them. And, in spite of himself, he was somewhat won over: without appearing to relent or altering his rhetoric, he was obviously quite pleased with Sanjay’s new toy; gingerly, inquisitively, he tried out the keys himself — he was adept at the harmonium — taking stock of its brazen, tinny sound.

Not everyone was happy, though, about Shyamji’s move to Sagar Apartments — not, for instance, his younger brother Banwari. Tall, dressed spotlessly in white, naturally affectionate and respectful, but with the innate helplessness and misplaced pride of a younger brother, he circled about, gazing downward, a small area in the sitting room in Borivli, torn between wanting to complain about Shyamji and defending him to his wife and the rest of the world.

‘Our father wanted things to be divided equally between us,’ he grumbled, neglecting to remember that he earned very little in comparison to his elder brother, and that what he did came courtesy of the ‘tuitions’ Shyamji arranged. His eyes were bloodshot, perhaps from lack of sleep — but, actually, they were always a bit red. ‘I didn’t get my full share when we left King’s Circle.’ Suddenly, he looked up, and, in a single god-like gesture, decided to physically shrug off the whole business, and became, at once, sentimental and shrewd: ‘Anyway, he knows more than I do,’ managing to sound both utterly sincere and offended, ‘he is my gurujan.’

Pyarelal didn’t — couldn’t — say anything, although he always had an air about him simultaneously of compliance and complaint; he only raised an eyebrow in judgement, with the dancer’s poise and suggestion. But Tara, his wife, grumbled quietly but audibly — everyone carried about with them expressions of fortitude, insider knowledge, and suppressed insights, and did nothing but blink slightly yet tellingly at any mention of Sagar Apartments.

For one thing, the flats in which Banwari and Pyarelal lived with their families — they had two and three children respectively — were too small; rudimentary one-bedroom affairs which had looked welcoming and larger than they really were when they were new but now silently exacerbated their nerves. They lived in them almost festively, investing them with all the bustling, makeshift energy that homes have. But they’d have been ready to go anywhere else. Oddly, they missed the congestion of King’s Circle; there was nothing to replace that sense of being surrounded by human activity, with its own untidy ebb and flow, in this environment. There was no nature either; only shops and, from the balcony, the prospect of fresh air. Occasionally, a crow would alight on the balcony, breaking journey between two invisible points in the outskirts of the city, looking into their lives, the assorted jumble of furniture and musical instruments in the small room, before the younger children rushed forward to chase it away. There was no other representative of nature’s variety here except this sly intruder.

‘No one knows what it takes to travel from this place to the Taj and back twice a week,’ Pyarelal muttered, and his words embodied, like an epic, the entire terrible, many-stopped journey; by ‘no one’ he meant Shyamji.

But these sentiments weren’t conveyed directly to Shyamji; the medium who buzzed them into his ear was his mother, mataji.

‘You’re doing well, beta, by the grace of God and the good deeds of your father. Lekin , beta, don’t forget Tara and Banwari.’

* * *

DURING SHYAMJI’S absences in England, Pyarelal became both Nirmalya’s accompanist and teacher, guiding him about the outlines of ragas, helping him to memorise the compositions Shyamji had taught him. They spent hours together sometimes, from late morning to afternoon, the boy ignoring but protected by his father’s existence, the handsome man in the suit, going out of the apartment, then coming back, somewhere on the margins of his consciousness. At such times, the boy was the real monarch, with the day and its luxuries entirely his own, as well as being a fugitive with the small, long-kurtaed older man for company. Just after practising a composition in the raga Yaman, or attempting the complicated, resonating web of Puriya Dhanashri, they would rise and go out onto the balcony to watch the sun set, the orange fragment losing its shape as it touched the horizon, becoming immense, maudlin daubs of colour after it had gone under. Pyarelal would light a beedi with his usual mixture of stealth and furtive theatre, as if all the world had no other concern but to catch him red-handed in the act. Then he would embark on a piece of proselytising, half monologue, in which he’d talk about how the movement of the universe and planets and the pull and push of the tide were all connected to laya, the tempo and rhythm of the compositions they had sung, and were indivisible from it. ‘ This is laya,’ he’d say, gesturing grandiosely toward the water into which the childlike fragment of the sun had disappeared, ‘this movement of brahmanda ,’ obviously transported and moved by his own words, although it was probably excessive to call the view brahmanda . By the orange-rimmed ocean, reflecting the light still spread everywhere in the sky, the Marine Drive bristled with droves of impatient cars departing from offices.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.