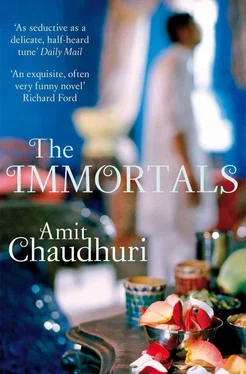

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He knew, however, never to presume to call himself Nirmalya’s ‘guru’; you could see from his face sometimes that he was greedy for acknowledgement, but he knew instintively where to draw the line; much of his life had been about knowing how far to advance, and when to stop. Importantly, Nirmalya, too, never made the mistake of thinking he was his teacher. Pyarelal was his accompanist, that was all; he was also something else, true, for which Nirmalya’s feelings were becoming deeper and more abiding, but that ‘something else’ had no name or official status.

‘You should be careful, baba,’ he said, ‘about singing “re pa” or “pa re” in Bhairav. That makes it sound like Shree. This is how Bhairav goes.’ And he sang, sa re ga ma pa, ga ma dha pa ga ma re sa. This was a morning session — when, once, Pyarelal stayed with them for five days — not long after Nirmalya had finished toast and tea and a glass of sweet lime juice, and Pyarelal had sized up his omelette moodily and made short work of it. The sun that had gone down on one side of the apartment the previous day had risen undisappointingly from the other, and light now illuminated and made plain the various rooms. His voice was a whisper at the best of times; as if singing had become at some point a private pleasure for him, not meant to be overheard by the world, but by certain people only. When he sang for too long, or did taan patterns for Nirmalya’s benefit, playing the tabla at the same time (a difficult, foolhardy thing to attempt, singing and playing the tabla at once, an act that Pyarelal plunged into again and again with an unthinking, almost masochistic doggedness), the boy noticed that his voice eventually cracked — the effect both of being out of practice and of relentless beedi-smoking.

When it was evening, and the immense, plush sitting room lit only by a couple of lights, while the great city glittered outside like a chimera, they would descend solemnly upon the sofa and the boy would play him some of his records — not the old collection, part of which had been procured directly from America, rare and precious as the world’s treasure, the long-haired angelic choirs of Crosby, Stills, and Nash and the others who’d gathered for that sunstruck week at Woodstock, all of which had one day, unaccountably, transformed into so much dross for the boy, but the Hindi film songs which he had discovered belatedly in the twilight of his growing up and adolescence, from the fifties and sixties, when he was not yet born, or was about to be, or had barely come into the world. ‘Listen to this,’ said Nirmalya to Pyarelal, and, of course, the older man had already heard the songs from when they’d first been sung, and he nodded and they sat listening gravely as the stylus stopped its hissing and Kishore Kumar began to sing ‘Chhod do aanchal zamana kya kahega’, Nirmalya reiterating his discovery with the satisfaction, almost, of having invented that bygone world, the other, already superannuated, rejuvenated by the rediscovered songs and the younger man’s faith in them.

In the acute loneliness of Nirmalya’s life, these hours with Pyarelal were animated with actual happiness. For Pyarelal, too, it was an extraordinary transposition; being here, in this apartment. And he worked hard with the boy; he went beyond his brief, although — perhaps even because — he was not his true guru. At lunch, he was never comfortable at the large glass table, with its grid of mats and cutlery carefully laid out, sitting with Mrs Sengupta and Nirmalya, confronted, in a strange kind of isolation, with the variety of china. Rotis were made for him, because he was not a natural rice-eater, and he tore these delicately, shaking his head slightly, as if he were in a private conversation with the bits of the roti that he dipped in the daal, and as if he could, by keeping his eyes fixed on the plate, wish away the context of the dining room. The thick glass dining table on elaborate legs was the only place where Pyarelal was uneasy; then it was back to discussion, perhaps a temporary parting of ways, then practice again.

The boy was fond of Pyarelal, and, spontaneously and without calculation, took advantage of his love during this residency. ‘Pyarelal, could you tape the tabla thekas for me?’ or ‘Could you tell me how Asavari goes?’; and the man would comply. Learning with Pyarelal was a form of playfulness, even competitiveness, in which the older man was always surrendering to the younger one. ‘Well, that taan is too difficult for me; you do it,’ Pyarelal would say, looking glum and pleased. He wasn’t lying; he was exaggerating. His love for the boy made him, during these hours of practice, ingenuously overplay his limitations.

By the end of the fourth day, the boy had actually grown a bit weary of this camaraderie; once or twice, he caught himself wanting to be alone, and tried to keep this fact from himself. But Pyarelal, attuned finely to the unsaid, sensed it, and it hurt him and made him behave badly at dinner with the servants who were intent on serving him daal or chicken, shooing them away peremptorily, or barely acknowledging them in a curt, bureaucratic way, as if they had no business being there — and so further aggravating Nirmalya’s belated but untimely sense of being intruded upon.

The next morning, as if to consolidate the illusion that he was going to be with them for many more days, Pyarelal finished his pujas, and, as he’d been doing for the last three days to everyone’s slight embarrassment, paraded the flat with three lit incense sticks (from a bundle Mrs Sengupta had given him), pausing before various icons and deities scattered everywhere in the form of decorations, as well as pictures and portraits of the Senguptas’ long-departed parents, closing his eyes, bowing and muttering some sort of a spell, waving the incense sticks, then hurriedly, self-importantly, resuming his tour before suddenly stopping in exactly the same way before the next picture or likeness. This extraordinary demonstration had led, partly, to Nirmalya’s frayed nerves; but, on this last morning, he didn’t know what to feel — whether to be touched, or thankful that it wouldn’t be happening tomorrow.

Before ‘guru purnima’ that year, Tara, Pyarelal’s wife, dropped a hint:

‘Baba, won’t you give your guru something?’

Everywhere that evening, under the light of an immense full moon, disciples and students of a variety of accomplishments would go throughout the city towards their dance or music teachers with yards of raw silk in packets, awaiting to be tailored into kurtas, or with flat red boxes crammed neatly with sweets, the thread with the shop’s name faintly printed on it knotted professionally and efficiently round the box; then, with a mixture of apprehension and self-effacement, touch the teacher’s feet and leave the packet wordlessly next to him. Nirmalya stared open-mouthed at his extortionist — uncertain of whom she was talking about. She was smiling, so it could all be put down to teasing. The temerity — she obviously meant Pyarelal.

‘How dare she!’ said Mrs Sengupta. ‘You have one teacher — and that is Shyamji. How dare she suggest anything else?’

The boy ruminated on this. And, of course, he wouldn’t give Shyamji anything — it would be too formal. He abhorred not so much the act of giving as the exhibition of devotion; he hated excess and the display of something as private, as closely guarded and unquestionable, as his reverence for his teacher. And, happily for him, Shyamji wasn’t that kind of guru; the almanac and the waning and waxing of the moon didn’t in any way interfere with their relationship.

‘Well, he has helped me a lot,’ said Nirmalya, divided and in thought. He meant Pyarelal.

‘Oh, it’s just that Tara wants something — she looks at you and she sees an opportunity,’ said his mother, exasperated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.