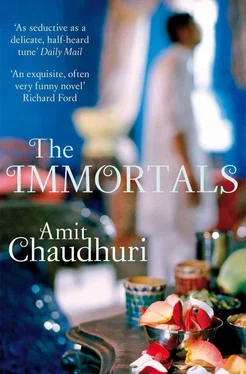

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

THERE WAS no great change the following day; from afar, Nirmalya could see Jumna squatting at one end of the drawing room, cutting swathes across the floor with the grey wet rag. Nirmalya was unperturbed they’d be leaving Thacker Towers. Then, the day passed and dwindled, the hard glitter of the Arabian Sea and the curving panorama visible from the balcony becoming the inevitable scattered nighttime dazzle.

More and more, he felt philosophy was his future; that he had to have his say on various mysteries — God, Being, consciousness, the self, etcetera. He’d long finished the chapters on Croce and Santayana and Nietzsche in The Story of Philosophy ; he’d responded with an innocent, assenting delight to the Santayana and the Croce, but Nietzsche and Zarathustra had maddened him with incomprehension. Only Spinoza he’d formed a special fondness for, without understanding him at all, but because it seemed that he’d proved, with a logician’s tools, that God and the universe were one thing. What a wonderful hypothesis, and how magical if it should be irrefutable! He turned to a book in his father’s study, a Grolier classic (one of a handsome bound set his father had purchased from a distant, once-youthful regard for masterpieces), to read, minutely, the steps in logic by which Spinoza had demonstrated his argument: his mind glazed over. A phrase stood out, ‘God-intoxicated’, which, a note said, had been used once of the seventeenth-century philosopher. Gulp by gulp, in the air-conditioned study, he swallowed civilisation.

As his parents made sketchy and unserious preparations to move to the suburbs after a year, discussing it half-jokingly amongst themselves, he thought increasingly, too, of gods and the divine nature of the universe. At thirteen, he’d dismissed God as a fiction; now, through Tulsidas and Kabir and the pseudonymous authors of the classical compositions, and their constant invocation of Krishna’s lips, his eyebrows, his antic childhood, Shiva’s tangled locks, his undecipherable moods, silences, and fantastic temper, Nirmalya was made to laugh at how profligate and real the universe of the gods actually was. Unkempt, loitering in Joy Shoes sandals, he was trying to make sense of the anarchic creation of the poets. How messy that world of eternal beings was: Shiva’s matted hair infested with the moon and the Ganges, as if they’d nested there like cheap trinkets or bats rustling inside a den or ruin; and all the buttermilk spilt in Yashodha’s kitchen as Krishna rummaged clumsily among the utensils. The songs were full of such workaday calamities and disturbances.

As he walked down the driveway and then out of the gates of Thacker Towers, he’d be observed warily by the security guard, and sometimes glanced at, with sudden recognition, by the driver of his father’s Mercedes. What was this boy in the kurta all about? Neither the driver nor the guard had quite decided. The guard knew by now that Nirmalaya wasn’t a student who’d wandered into the compound, but was the son of the man on the twentieth floor who, flickering in his suit, went to work in the white Mercedes.

Nirmalya, now that his sojourn in Thacker Towers was coming to an end, felt more than ever that his home, his calling, were elsewhere. He walked past Snowman’s Ice Cream Parlour, where boys in slim-fitting trousers and girls with horizontal bits of midriff afloat playfully above their jeans laughed loudly and devoured the fragile ice-cream cones they held in their hands. Were they laughing at him? Rows of expectant motorcycles stood crowded in the parking space in the centre of the road, booming at the touch of a boy’s hand, roaring as he turned his wrist and straddled the taut, muscular epidermis of the seat, always exploding into speed rudely. He didn’t care. He was preoccupied with existence itself, with the question almost made nonsensical by repetition, ‘Why do I exist?’

‘The question in itself is not as interesting,’ he jotted down in a little notebook he’d bought from a small, fragrant, forgettable stationery shop in the shopper’s arcade near Thacker Towers, ‘as the way, or spirit, in which it is posed. “Why do I exist?” might be the beginning of an intellectual query, a scientific or rational investigation, the answer to be arrived at by reasoning and deliberation, at the end of which there will be no satisfactory answer. Or it might be a cry of pain, “ Why do I exist?”; here, the answer is no longer important. The answer lies in the question, which is the result of suffering.’

He avoided a car and crossed the road. He’d felt pleased after writing those sentences. His sympathies lay with the cry of pain; if someone asked him, What have you suffered? he’d have to say, Very little. Yet, in a mood of visionary despondency, he walked, in his incipient philospher’s agony and undecidedness, through this area that was still, every day, changing shape, new lights being added, still newer buildings coming up, with parks thrown willy-nilly in between, for people to explore and circle round in in the evenings, and wildernesses and unkempt places being constantly curtailed, but still surprising you by springing upon you at times. Walking, he found himself before a strange, wide, white building, that seemed to have descended, like many of the other things he’d encountered, laconically from nowhere, providing no explanation or justification; he knew, from some useless snippet of information stored away in his head, that it was called the World Trade Centre. He stood for barely a moment, trying to reconcile himself to the building’s apparent lack of function; neither trade nor the world seemed to have anything to do with it. Perhaps it would grow into its name? Was it here that his mother had come visiting briefly two weeks ago, getting out of the car and then advancing in a predetermined way, as if this environment were already familiar to her, through a litter of unused shop space in this ghost town called the World Trade Centre, till she finally arrived at an outlet with two perfectly ordinary human beings, from whom she bought, after giving the matter some, but not too much, thought, tiny stick-on bindis arranged in rows on a piece of paper? And had he been with her, inside? Nevertheless, the building struck him as at once charmless and completely unexpected; he couldn’t imagine ever having had anything to do with it. When he returned to the apartment, he heard excited voices coming from the room in which music was usually practised, accompanied by a few incongruous taps on the tabla, and sporadic, short-lived chords on the harmonium. They were taking a break. Shyamji, his face as animated as a child’s with speculation, was asking, ‘Then where will you go, didi? Will it be a different side of the city?’ Banwari was sitting Buddha-like on the coir mat, smiling faintly, listening, unmoved by the many revolutions of the earth, his hands still on the tabla. ‘Come to our side,’ Shyamji said, biting into a biscuit, entertained, obviously, by this idea of geographical proximity translating into a form of spiritual closeness. ‘Then you will be near us.’ And then, suddenly, he spotted the boy by the door, and his expression changed into one of strange, guileless mischief. ‘Kya, baba, didi says you never liked this area at all?’ Shy and exasperating as a new bride, the young vagrant in the narrow churidars and severe-looking khadi kurta smiled and nodded quickly and escaped; avoiding, as ever, ordinary conversation with his guru, never able to see his teacher without reverence, but never, because of his pride, able to behave with the expectedness and ease of a student. ‘Now where did he go?’ Shyamji asked Mrs Sengupta, puzzled, and, his thoughts already changing, drank from the remaining shallow pool in his cup.

* * *

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.