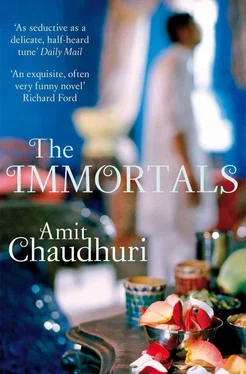

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I’m sorry, madam. What can I do?’ he said, sullen and obdurate, falling back on the phrase that was a favourite whenever he was in a sticky situation with his superiors. ‘I have orders from office.’

Tentatively, Wilson began to walk around the drawing room, where he’d never been before, either as visitor or guest, with a notepad and pen in his hand. ‘It’s a disgrace,’ said Mallika Sengupta in a clear voice, as the figure moved further away. ‘I will complain.’

‘These will stay,’ he thought, looking at a rosewood cabinet and the large L-shaped sofa with a qualified but proprietorial eagle eye, as if he’d formed some sort of kinship with them. He barely glanced at the Grecian urnlike table lamps. At a huge stretch of carpet, deep and ruddy, he paused, undecided, and glanced at the paper in his hand. He was in a peculiarly emotional mood, at once self-effacing and blithely, insularly unstoppable. The only time he smiled slightly was at three photographs on a rosewood shelf, a close-up of Mrs Sengupta’s face from ten years ago, her charming uneven teeth showing in her blissful smile, and another of Nirmalya when he was eleven and pudgy, proudly wearing a zip-up T-shirt a relative had sent him from Europe, squinting unthreateningly (those were his last days without spectacles) at the sunlight, with parents on either side, against a wilderness that was actually Elephanta island; then another one in which Mr and Mrs Sengupta and nine-year-old Nirmalya, dressed for the Delhi winter, were posing beside a severe woman with a patient but unprevaricating gaze, who turned out to be Indira Gandhi. A spring came to Wilson’s step, a barely noticeable feeling of abandon; till, gradually, once more, he became serious and attentive. Around him, as if he were no more than a fleck of dust, Jumna reached casually with her jhadu for one of the many tables, and then wove herself towards the sofa to plump up a cushion.

When he left, he had the pained, wise air of someone who’d been far happier booking private taxis for Mallika Sengupta, and checking times of flight arrivals and departures. ‘Thank you, madam,’ he said, as if he were referring not to the grace of the last half-hour, but redeeming the small role he’d played in her life.

‘How is your son?’ said a woman whom Mrs Sengupta knew well from these occasions, a Sindhi businessman’s wife. Mallika Sengupta, startled, didn’t know where to begin. They had plates of dessert on their laps, the sort of juxtaposition that was becoming increasingly popular in the business and corporate community, honeydew melon ice cream and semi-transparent, plastic-yellow jalebis. ‘He is reading all the time, very difficult books,’ she said, laughing. She was always defensive about him. ‘What will he study?’ the woman asked, persistent. ‘MBA?’ Mrs Sengupta was pleased, cruelly, because she knew her answer would disturb her companion’s ingestion. ‘He says he wants to study philosophy,’ she smiled. The woman paused, tried to capture, with her spoon, a slippery fragment of ice cream, and said with averted eyes, ‘Very nice.’ Then added, as if speaking of a rare condition she was not going to condemn or probe too deeply: ‘So he is not into money.’

To regroup, she asked: ‘You are leaving this side of the city, Mallika? Where do you plan to go when your husband leaves the company?’ ‘Bombay is such a huge place, and so expensive,’ said Mrs Sengupta, glancing at her reflection to check if her hair was all right; the wall had large glass panels that doubled everything — the fluted frames of the chairs, the doorways opposite opening on to corridors, the hair held ornately in buns or falling darkly upon shoulders, the glow of the chandelier — with various degrees of approval. ‘My son’, she said with secret pride, ‘says he wants to go somewhere quiet and green.’

* * *

FINALLY THEY LEFT that side of the city forever — too cheap a word, whose meaning you don’t quite get to grasp in a lifetime; you only use it self-indulgently, for a luxurious and elegiac sense of closure. Instinctively, they didn’t use it; they didn’t believe in ‘forever’ — the company had gifted them, almost two decades ago, a permanent sense of the future. Only much later do you learn that there’s no going back; learn it, an incontrovertible, minor lesson, not very difficult to grasp, then move on.

This, maybe, was the ‘quiet, green place’ that Nirmalya had been thinking about, but whose existence he’d never really suspected; a lane off one of the downward slopes of Pali Hill, a blue plaque announcing its name hanging by two rings from a pole at the base of the lane, which swung in a monsoon breeze in an intrepid, self-contained way, a gate opening on to a building, a second-storey apartment, three bedrooms, roughly fourteen hundred square feet, just a little more than a third of the flat in Thacker Towers. It was as if, wandering down Thacker Towers, they’d discovered an annexe no one had noticed before, an annexe whose balcony opened on to a silent neighbour, a jackfruit tree — and they’d decided never to return to the main flat.

The way to the city was long; sometimes it took as much as an hour. Every morning, Apurva Sengupta — he now had a post-retirement job as a consultant in a German firm — went back to it, past the upturned hulls of fishermen’s boats on the sand in Mahim, the new Oil and Natural Gas Commission township breeding in the swamp in the background, the Air India maharaja on the left, full of a droll and emphatic sincerity, promising seven flights to London a week; off he went in a sturdy white Ambassador he’d bought from the company, and in which an air conditioner had been fitted. They’d got used to air-conditioned transport, the sealed air, the busy, glinting, ragged world kept at bay by glass; they couldn’t, any more, imagine long journeys without it. The air conditioner, however, hadn’t been part of the original engine; it had been transplanted in a garage and installed as an extra, and it took something extra out of the machine. Slowly, shamelessly, it was reducing the engine’s life. No matter; it gave the Senguptas comfort — every blast of coolness on a hot, uncontainable day was welcome; it turned the interior of the Ambassador into a time capsule, a seamless continuation of their old, familiar life in the Mercedes, which they’d bid farewell to without much of a pang. But, since the air conditioner wasn’t built into the engine, it worked off and on, it stopped when the car stopped at traffic lights and went into fan mode, warm air emerged from the slats and brought the Senguptas back to where they were with a wave of irritation. Then, as the light changed to green and the car moved on, there was relief again.

And, in spite of their satisfaction with the new charming little flat, with the quiet lane off Pali Hill and its gulmohur trees with fan-like leaves and churches that emerged silently but busily at the end of a street and reminiscent bungalows that still belonged to Goans, they felt compelled to make the trip, each day, to the centre of Bombay, to Dhobi Talao and Flora Fountain, to partake of their old life: the life they considered shallow and a bit fake. Like interlopers, they arrived, having burnt an hour’s worth of fuel on the way, at the club they used to frequent; ordered food, feeling dishevelled after the journey; disappeared into the spacious, forgiving gentlemen’s and ladies’ bathrooms to splash water on their faces, adjust the bindi on the forehead, smooth their clothes; then, like people who’d been pacified and made whole, returned to their sofa and ate wonton soup and fried rice or a plate of steak sandwiches.

One day, Mrs Sengupta, an hour after her music lesson, found Shyamji at the top of Pali Hill, determined but anguished, his Fiat uncooperative and impenetrable, he about to push it up the slope, while his driver, collar hanging back from his bare brown neck, stood next to the car, one arm plunged into the window, his hand on the steering wheel. Mrs Sengupta was seized by a moment of pity; leaning out of her window, she surprised him with, ‘Shyamji, I will drop you — where are you going?’ Nirmalya, her only company in the back, smiled indecisively. Shyamji smiled too, in a pained way, as if neither he nor the second-hand car was to blame, but something more mysterious and inscrutable that had acted up this hot, dazzling morning.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.