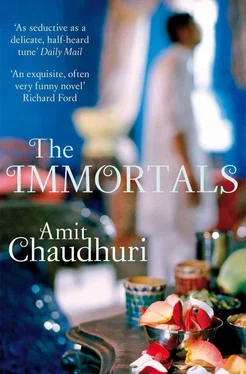

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

* * *

NIRMALYA — though he still hadn’t completed college — wanted to apply to study abroad. ‘There’s no philosophy degree here worth its name,’ he said, contemptuous and impatient after a day spent loitering intractably around the portals of the college at Kala Ghoda.

He found an ally in his mother, who, otherwise, couldn’t bear to let him out of her sight, but who became very serious and nodded at everything he said these days, as if it were of the utmost importance. His mother, who’d disciplined him as a boy when he would plot new and untested devices to ‘bunk’ school, had recently become a sort of acolyte. For thirty years her life had been designed by her husband and by the company; now, like a beacon representing some other order, her son, untidy, brooding, with an opinion about everything, appeared on the horizon.

‘He doesn’t want to be like you ,’ she said, berating Apurva Sengupta, as if he and his kind were a species of obstreperous, careless dinosaur whose day had come.

Mr Sengupta smiled. He knew that, although his own days might be numbered, his type, the company type, ambitious, brisk, democratic, convinced in the sacred value of entrepreneurship, was bound to flourish — it made him a bit sad, knowing his son had decided not to be part of this proliferation — in a way that dinosaurs never had managed to. His type would populate the world in unforeseen mutations. Money was like a sea-breeze blowing inland; gentle now, but threatening to uproot everything. He, Mr Sengupta, had never really seen money except in its genteel aspects, had never seen its unbridled form; but he could smell its distant agitation. Nirmalya appeared immune to the smell, or determined to ignore it.

But, surprisingly, Apurva Sengupta felt affectionately about his son’s interest in philosophy; just as you might listen to a piece of music which numbs you to the present and makes your nerves tingle to the daydreams of who you were thirty or forty years ago, Mr Sengupta felt a momentary, youthful enchantment. Then the present returned to him all at once, physically and emotionally; you could not escape being who you were now; he was worried by Nirmalya’s intention to study philosophy and the mundane but unavoidable questions it raised. It seemed quite right, and wonderful, to Mr Sengupta that Nirmalya’s first follower was his mother; there was a small but revolutionary change taking place in his family before his very eyes; and who knows — given time, he too might be converted. What was parenthood, after all, but an apprenticeship (a belated apprenticeship in Mr Sengupta’s case) to the possible greatness of one’s children?

But to go off to England, as Nirmalya wanted to, soon, insatiable, suddenly, in his conviction that the real hunt for knowledge would begin once he’d transplanted himself there — that passage would require funding; where would the funds come from? Nirmalya was too unworldly, too insulated from the material capriciousness of human existence, to be bothered with these particulars. It was left to Apurva Sengupta, who’d once managed a company, to now manage his son and his unworldliness. Mr Sengupta would have to quickly review his savings (which, under Mrs Gandhi’s tax regime, had been small, most of it going every month into a strangely futile insurance premium) and apply for educational loans. It was expensive maintaining a saint, a mystic. Wasn’t it Sarojini Naidu who’d said — Apurva Sengupta’s mind went back to his shabby, peripatetic college days and to the freedom struggle — that it cost a lot of money to keep Gandhi travelling third class? Decades had passed since that remark, exquisite in its irony, had been made and those excitements burnt out into the straight-faced pursuit of well-being in present-day existence. Mr Sengupta smiled as the words — full of a tolerant, even affectionate, mockery he recognised while taking up the task in hand — came back to him.

‘King’s College, London,’ he said, returning from work, the look on his face at once querying and pleased, like a boy who suspects, but is not entirely certain, that he’s carrying a piece of important news. ‘Jane says it has a good philosophy department.’

‘Jane’, thin, hesitant, but large-heartedly helpful, was part of an entourage from the Commonwealth office in whose honour a cheerful and efficient business luncheon had been organised that day, in a conference room in the basement of a five-star hotel. The topics covered in the meaningless, happy hum between the suited Indians and the awkward English, some of them making jerky, shy movements of the head, others complacent and impenetrable, had included foreign investment (naturally), mergers, the annual growth rate, trade restrictions, and, between Jane and Apurva Sengupta, for about seven to ten minutes, philosophy departments.

And so Nirmalya became a correspondent, and entered, reluctantly, his first transcontinental communication, in which someone from the department, a Mrs Sandra Dixon, pleased and ruffled him by writing back to him and sending him, obligingly, an envelope thick with forms. He sat down heavily with them in the morning upon the bed, bending forward, placing them against the hard surface of an exercise book, filling them out laboriously, progressing slowly from rectangle to rectangle, sighing from the start like a sick person (he had a condition close to dyslexia when it came to completing forms; it filled him with a subdued panic and lostness). When it was done, he felt an indescribable sense of liberation, as if he’d never have to do it again; he went on to the veranda to get some air and to survey the unfolding of the everyday. Weekly, now, long white envelopes began to arrive, with postage stamps that had, upon them, a ghostly impression of the head of the Queen of England.

The letter they’d been waiting for but not expecting crept in beneath the door one afternoon with aerogrammes and statements of interest rates: acceptance.

When Nirmalya had ripped open the envelope and excavated the letter, he read, with the same swimming eyes of the unhappy form-filler, the message in the neat, punctilious, by-now-familiar type: ‘I am pleased to say that. .’ He took it to his mother; she opened her mouth in astonishment and then read it out, in her naive, stumbling, insistent maternal accent, to her husband over the phone.

* * *

HE WENT WALKING around Pali Hill and the lanes of Bandra; in the afternoon, confronting dogs that lay curled up in self-contained, pilgrim-like repose in the middle of a road, or a tyre abandoned on one side without explanation; and in the evening, with the fruit bats hovering overhead. He was in a curious interim phase; unexpectedly leaving his childhood terrors and his adolescent anxieties behind, opening himself, for the first time, to the allure of the world — he was in a state of semi-retirement himself, secretive with his thoughts on books and music and this new locality, nothing to do for much of the time, as he waited to travel to King’s College. He had almost no friends — he’d gradually stopped seeing them, one by one — and he undertook his expeditions alone; his parents no longer questioned him about his irregular attendance at college. He was struck by everything here: the warm, loaf-like stones that made up the walls of the Christian schools; the pretty, tissue-paper-like bougainvillea (almost like something mass-produced by a greeting-card manufacturer) by the gates to the Goans’ bungalows causing him to stop, undecided, in confusion; at traffic junctions, as lines of cars negotiated transitions from Hill Road to Perry and other roads, sudden crosses rose up like sentinels behind the traffic lights; and churches sprang up between or in the corners of the interconnecting lanes. How different all this was from the Bombay he’d grown up in!

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.