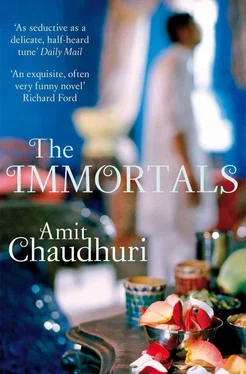

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She’d brought photographs with her today; she took them out of an envelope, one, two, three, four, and passed them silently to Mrs Sengupta half-recumbent on the bed. The first picture was of Salma and two other girls standing upon a hill, a bit unreal and over-made-up, at a discreet distance from the flamboyant (and largely out-of-work these days) Chunky Pandey in his wide-collar silk shirt. The other three photos were more of the same. It pained Nirmalya that the make-up, and maybe the situation itself, had taken away Salma’s glow in the photograph — the glow which was the first thing about her that had struck him, and which was her unique, indisputable and most natural allure — and made her indistinguishable from the other two girls, as well as from the many girls who form the background of the numerous epic scenes in Hindi movies. In each photograph, she looked self-conscious and stiff; and you could feel her stiffness. Nirmalya studied the pictures and returned them to the envelope.

‘Bahut achha,’ he said wryly. ‘Very good.’

* * *

HE HAD TO HAVE a photograph taken for his passport; and he decided impulsively not to go to a studio in the vicinity, to one of the shops on Linking Road or Hill Road, but — because he needed an instant photo; time was running out — all the way to Churchgate.

He’d begun to use the local train; he’d never learnt how to drive, of course — his childhood had been almost entirely chauffeur-driven, and then a certain laziness about learning to drive after he’d finished school, which was when most of his friends had swiftly acquired the skill, when they were still not eligible for a licence, but were eager and unstoppable: a laziness at that point had coincided with and enlarged into a superiority to do with anything his contemporaries did, anything that was the natural course of events in his father’s world or his friends’, and he deliberately missed his chance at taking possession of a car. And this refusal had branched out into his indefatigable capacity for walking, which depended on, and emphasised, his increasing, and on the whole self-contained, loneliness, leaving him to explore both the suburbs, the fortuitous ups and downs of Bandra and Pali Hill, and the alleys and familiar roads of the city he’d grown up in, on foot.

He went now, taking a half-empty two o’clock train from Bandra to Churchgate, to the Asiatic department store near the station, because it had the only passport-photo booth in Bombay. Edging past unflappable, prodigious housewives, he paid for a token at a counter and then, avoiding a mirror, climbed expectantly up the stairs. He was suspended momentarily between two levels on which toys, stainless-steel utensils, yards of cloth appeared and disappeared in an exchange of gazes, words, and consultations, the thin salespersons in white taking out and then once again silently returning the folded bales to their places. There, before him, on the first floor, was the booth, flanked by long counters busily selling things. A lone man in uniform advised him sombrely about what he was to do when he was inside: ‘Be careful not to shut your eyes when the flash goes off ’; ‘Drop the token and stare at the green light before you’; ‘Adjust the stool to the correct level’; all in a low, inhuman, deadpan voice. ‘Yes, yes,’ said Nirmalya, vaguely disturbed; he went in and pulled the curtain, feeling nervous, and also a guilty, solitary excitement, because there’s an unmistakable hint of sleaze about cubicles and drawn curtains. Much as he tried, in that narrow island in the milling hubbub of the shop, the flash, both times, went off a moment before he was prepared for it, leaving him feeling somehow chastised when he emerged from the booth. The man, who’d felt snubbed by Nirmalya’s ‘Yes, yes’ now had the inevitable tranquillity of the powerful; when the photographs fell with a buzz into the slot, he forbade him with an impersonal, imperious gesture to touch them until a few minutes had passed. Nirmalya dawdled there, distracted, as his image composed itself bit by bit upon the whiteness; when he finally picked up the photos, he saw the sense of being imprisoned inside the cubicle had robbed his face of its strangeness, had made it ordinary and disposable as the paper it appeared on. He felt no attachment to it whatsoever; given a choice, he’d have denied to the passport officer it was his picture.

‘Ma, you know the train’s a good way of going to the city,’ he revealed to Mallika Sengupta. She looked with loving disbelief at her son, as if it were another one of his wild, testing ideas. The train! It wasn’t something they had ever had any reason to use; when they’d lived in the city and had to visit old friends in Bandra and Khar, the long drive through Breach Candy into Worli and then Cadell Road and Mahim had been the occasion for a magical, purely private, journey, unimpeded, on the whole, by traffic — there were so few businesses, then, on the outskirts — during which the city changed itself several times, seamlessly but unpredictably; and then back again. And now Nirmalya, in his frayed, slightly dirty corduroys (he would not put them into the wash) was suggesting trains; almost as a form of enjoyment! How quickly things had changed in the last few years!

They still felt the need, of course, to go to the city three or four times a week; the old life was a fix they suffered almost physically without — despite the prettiness of Bandra, despite their avowed contempt for that existence comprising parties and elaborate hairdos. They took a taxi usually, often with shrill Lata Mangeshkar songs playing from the speakers at the back; or, when Apurva Sengupta was picked up in the morning by a colleague, they followed distractedly in the fitfully cool Ambassador. But it cost money, the journey; hundreds of rupees every week at the Shah and Sanghi petrol station at the corner of Breach Candy and Kemp’s Corner. The taxi fare, each time, was almost a hundred rupees.

‘And cheap,’ added Nirmalya. It was not like him to be troubled about such things. Nevertheless, he was aware in a faraway, theological way that there was no company now to foot the bills, and he worried — this was a new and pleasurable anxiety — slightly for his father; and, of course, he quite enjoyed embracing whatever little poverty he could. Travelling by the local train was his way of briefly, innocently, taking on a disguise, of insinuating himself into the life of the multitude.

‘Really? Where does it go to?’ asked Mrs Sengupta, enthused mildly by the thought of saving the taxi fare; excited, too, to be in a new partnership in this foray with her son. Besides, the idea of saving money had always exercised the puritan in Mr and Mrs Sengupta; the actual practice bored them.

‘Churchgate Station,’ he said.

‘Let’s try it tomorrow,’ she replied, negotiating.

They took a taxi — not to the city this time, but to Bandra Station, and, while Mrs Sengupta hovered in the background, near the entrance, watching vendors, abstracted beggars with bandaged, amputated limbs, and auto rickshaws suddenly roaring back to Bandra, he bought two first-class tickets. This theoretical and implausible luxury gave him much pleasure; ordinary tickets were only two rupees; and, if you paid fifteen rupees more, you travelled first class, which was identical to second, except that the seats were slightly cleaner, and, instead of the raw, ubiquitous perspiration of vegetable vendors, errand boys, and people with part-time employment, you inhaled the odour, mingled with aftershave, of clerks and traders’ accountants, their monthly passes (naturally they didn’t buy tickets) in their shirt pockets. The compartment was less than half full because it was half past two; he — because she was so nervous about her feet and balance — had to help her up, clasping her hand tightly; once she was in, she looked about her with a mild, puzzled smile, like one who’d entered a somewhat makeshift drawing room at a suburban social gathering, and then allowed herself, elegantly, silently, to be led to her seat. People seemed to recognise her, and looked at her respectfully, as if they knew she was Mr Sengupta’s wife and what that meant; and then returned almost immediately to their own thoughts. She settled into the seat, without comment, trying to experience the strange magic in the compartment, unworried, for the moment, that the seat was hard and that she had a lingering backache. He glanced at her with a deep, uncategorisable love. Just as the train began to move, barefoot children and tiny, intrepid men with fan-like bouquets of pens jumped on board, displaying them briefly to one tolerant but uninterested person after another; the children took around small plastic packets of peanuts, saying, just a little too familiarly, ‘Timepass?’ Mrs Sengupta looked nonplussed and charmed. ‘Let’s have some peanuts,’ she said, with an air of someone consenting to behave much more rashly than they normally did. Then, surrendering to the breeze, which generally annoyed her when she was in a car because of what it did to her hair, making her quickly roll the window up, she sat munching peanuts with dignity and an impenetrable delight; until, carefully, entering a different phase in her consciousness of the journey, she put the packet into her leather handbag.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.