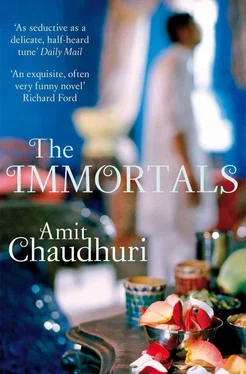

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They arrived, pennant-heralded, at the dun-coloured driveway to the hotel, and got out at the immense porch. A distant gust of chill air greeted them. The hotel, with its line of palm trees, had risen out of nowhere like something in a European fairy tale; it was surrounded largely by waste land. Mr Sengupta had a lost but cheerfully inquisitive air, like someone who’d been forced to take a long diversion and had stopped accidentally; and the doormen willingly cooperated in this little piece of theatre, and received him accordingly, calming him with smiles and bows as he entered. When they’d walked past the catafalque-like lobby, ignoring the small, glassy-looking men and women behind the reception, and settled into the understated but resplendent chairs in the coffee shop, burrowing finally into the heavy menus before them, running their eyes over varieties of Darjeeling tea and cake named and described in sloping letters, Nirmalya, who was looking out through the large sunlit glass windows into the brown tract of land outside, where, in the distance, a boy was squinting and squatting on the edge of a metal cylinder, said: ‘Baba, I don’t want to eat here.’

Apurva Sengupta looked again at his son in surprise, even wonder, as if he were reminded that the boy represented a puzzling, unforeseeable turn in their lives; he couldn’t help but laugh, almost with pleasure, as he used to when Nirmalya, as a baby, had first begun to exuberantly and insistently utter nonsense, and it had seemed so momentous to his parents. Then, too, he’d felt that fear mingled with joy, as if he’d never confronted anything comparable before.

‘Why, what’s the matter?’ he asked his son, without anger or condescension — just as he’d reasoned with him at different points in their lives, while cajoling him to go to school, for instance, or when leaning forward to the small unappeasable boy before he got on to a flight.

‘I can’t eat here,’ Nirmalya said, shaking his head slowly, the boyish face, little more than a child’s in spite of the moustache, full of an inexplicable hurt, the eyes almost tearful. ‘I can’t eat here till Shyamji is able to eat here,’ he said, eyebrows knitted, still shaking the head ominously.

What was this sudden onrush of love for his teacher — a love he seldom displayed openly? What had happened to this boy, for whom all it took to be happy once was to come home from school? Apurva Sengupta felt a twinge of concern, as he struggled to work his way towards a sense of how his son perceived the world. But they — the parents — didn’t argue or admonish; simply tried patiently to understand the truth of this outburst. Returning the ivory-coloured napkin to the table, Mallika Sengupta said: ‘No, I don’t like this hotel either. It has no soul,’ she concluded determinedly; and the father, still strikingly handsome and kind-looking, fundamentally an optimist and a person of faith, faith in the future, nevertheless wondered at the spectacle of his son, and nodded tentatively in agreement. They pushed the chairs back and rose; Nirmalya had already reached the open doorway of the coffee shop.

Smiling, but with a conviction that they were doing the only logical and admissible thing, the Senguptas followed their son out, leaving the waiters puzzled, Mrs Sengupta glancing tolerantly, without emotion, at the tray of cakes. They crossed the lobby, forfeiting the usual unconscious abandon and easy familiarity they felt when visiting beautiful, welcoming places in Bombay. The boy, in his faded pink kurta and jeans, was already outside in the heat, distant, self-enclosed, the wind tunnelling through the driveway blowing into his hair, as he stood oddly adjacent to a gigantic Sikh doorman. ‘Nirmalya!’ said his mother, coming out of the air conditioning and wiping her nose instinctively with a hanky, the merciless semi-developed expanses of Versova trembling in the heat; the Sikh doorman, an anachronistic but unignorable ornament, half-turned in her direction with an astonishing jerk of recognition and reassurance and smiled.

* * *

SHYAMJI WASN’T WELL; he’d developed a cough. It interrupted him again and again like a hiccup that wouldn’t go away.

‘Shyamji, what is this?’ asked Mrs Sengupta suspiciously, looking up from the songbook; her antennae were always tuned to illnesses.

‘I don’t know, didi,’ said Shyamji, peeved but distant, as if he were in no way responsible for the tiresome interruption. ‘I don’t have a sore throat.’

‘You should have it looked at.’

Meanwhile, it had begun to rain. June had changed to July without much rainfall, with only, on most days, an expectant, oppressive heat which made the shadows the trees cast in Bandra seem so timeless and seductive; and now, it was suddenly raining in bursts, agitating and disorienting the birds on the balconies, dissolving into a false calm later in which one leaf dripped patiently on to another.

In the midst of this late-arriving, swirling pool of shadow and cloud and wind, Shyamji became, temporarily, a migrant, moving from one suburban location to another, staying with students in Khar or Juhu who wanted to give him space and respite from duties and family while they looked after his needs, while enriching, of course, their own store of songs and even their lives by being near him. Sometimes, Nirmalya and Mrs Sengupta visited him at these places, getting out of the car after it had been parked on the side of a narrow lane in Khar, the road still moist and muddy with the print of tyre tracks after a brief shower, opening the gate, going in carefully, the scab-rough walls of the old house pale gold with the indecisive, intermittent sun, the small, mali-tended garden outside still wet, the flat leaves shivering with tiny rivulets of water, the bark of the tree seemingly dry and hard; as they approached the door, they could hear Shyamji singing with his students. A young Bengali family — two brothers and a sister — who had musical ambitions and had moved from Calcutta to Bombay for this reason, had rented this apartment.

‘Aashun, aashun,’ cried the older brother when he saw Nirmalya and his mother hesitating at the doorway; because he was well aware they were Shyamji’s students, and he knew them slightly.

The harmonium sighed as Shyamji hooked the bellows. ‘Aiye didi, aiye baba,’ he said. ‘Sit down here,’ he said softly, patting the white sheet that covered the bed. Although he wasn’t in the best of health, he was intent on being hospitable; and though he was in a house his students had rented, it was as much his house — perhaps more his — as theirs.

He looked tired, but undemonstratively happy. The fragrance and breath of the rains was always a gift that delighted human beings, and Shyamji was no exception.

In two weeks, in spite of the niggling cough, he was back to accepting invitations and giving in to demands. He said:

‘Didi, some people have been asking me to sing in a new Sindhi temple. Will you and baba also sing a song each? I don’t want to sing all the songs myself with this cough. Besides, more people should listen to you, didi.’

Mrs Sengupta’s role, in her married life, had usually been to sing a song or two on small occasions, after which someone, good-natured and anonymous, would lean towards her and murmur gravely, ‘I haven’t heard a voice like that since Juthika Roy!’; praise that would leave her, each time, happy as a tender seventeen-year-old, but then, as the sense of her body and spirit in time returned to her, essentially unfulfilled. Yet she could never resist adding another nameless venue to the ones her singing-life in Bombay had been dotted with; she agreed now, feeling, in spite of herself, the transient little-girlish excitement and nervousness she always experienced at these moments.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.