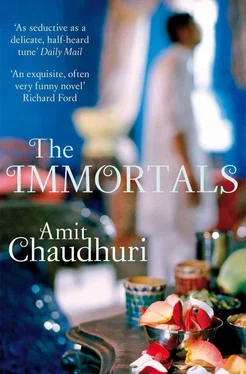

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Juhu Danda: he knew the place slightly. Their car had passed through it once on the way to the Neogis, when they were going to Khar. There it was, at the end of Carter Road opposite to the one from which he’d just returned; a colony of shanties, with dried bombill hanging between poles, the air awash with the rank, tantalising smell, men in shorts standing in the sea breeze, barefoot children running and playing in the space before the shanties, surveyed dispassionately in a few instants before the car moved on.

When she’d gone, his mother said to him: ‘Her name’s now Saeeda.’

‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

‘Well, that’s why she left all those years ago, you know. In fact, we used to live in Juhu then; your father, on returning from England, got his first job in Bombay, and was given a flat in Juhu. She fell in love with a Muslim and then married him. They have to change their religion when they do that, you know.’ For to marry a Muslim was to not only change your name but to give up your childhood and your future, to pass discreetly into a different world and mode of existence, to, in effect, disappear; only great and impulsive love could, surely, make one justify such an abdication to oneself. And yet was that, strictly speaking, true? After all, here was Anju, older, but still recognisable, the same woman who’d scooped him instinctively in mid-air when he’d leapt out of his cot in his exuberance.

‘Is she happy?’ he asked; for, briefly, he found Anju’s, or Saeeda’s, happiness had become his concern.

‘Her husband is a strict Muslim but not a bad man, she told me today.’ Such a belated sharing of confidences! ‘She herself is not a practising Muslim, but the children were raised strictly. The son is in Dubai, and the younger child is a daughter. Life is sometimes good, sometimes not so good, she said,’ said Mallika Sengupta, smiling, as if she was relieved that it was at least good in parts.

Anju came again one afternoon, this time with her seventeen-year-old daughter.

‘Namaste, memsaab,’ the girl said to Mrs Sengupta, and glanced at Nirmalya. Anju, leaning against the wall, looked on as if she was showing off something no one had suspected she had. She herself had obviously been attractive long ago; but the girl was exceptionally lovely to look at; tall, with a large oval face — and the mother seemed pleasurably resigned to being superseded by her daughter. There was a thoughtfulness about her that attracted Nirmalya, a reticence that made her quite different from the lissom girls in narrow trousers and tops, girls from his own social background he passed by every day on the roads, laughing and screaming innocently to each other, as if the world was theirs.

‘She’s a pretty girl,’ said Mrs Sengupta to Anju. Almost slyly, she turned her gaze upon the daughter. ‘What is your name?’

The girl’s eyes were focussed on the carpet. ‘Salma,’ she said softly, as if it were a word she did not use often, and then only with care and reluctance.

‘Kya karti hai?’ Mrs Sengupta said, speaking to the mother again, with a register of intimacy and a bygone commandingness. ‘Tell me what she does.’

‘Memsaab, she’s got a few small roles in films,’ said Anju, creasing her forehead deprecatingly. ‘Her father doesn’t like it, but I said to her — “Do what you have to do, but in today’s world be careful.” ’ She sounded apologetic, but she was a little thrilled as well — overcome, perhaps, by the irresistible, ancient charm of cinema. She was protective of her daughter, but a sort of distance separated them that was not just generational; perhaps she was also a little in awe of her, a little — who knows — envious.

So that was where this girl’s modesty, her inner glow, came from: it must be from that extraordinary sense of destiny that both cinema, with its timeless reassurance, and being seventeen give to you. She was set apart — the future had stored something special for her — she’d grown up in Juhu Danda, but she was a flower; lovelier than any other girl Nirmalya had seen for a long time in Bombay.

He saw her on the street once, at the corner of St Leo Road; she was with a friend; they nodded at each other, he awkwardly, not sure what to make of this Juhu Danda girl. And she came visiting again with her mother — always in cheaply tailored pale green or yellow salwar kameez outfits, looking like an apparition whatever she wore.

He had begun to think of Salma with a kind of yearning; there had been times in the past when he’d almost felt ready for marriage, his tortured, inarticulate heart palpitating for the arrival of the long-awaited instantly-recognised bride: there were occasions he’d grown tense with the as-yet unknown person’s imminent arrival.

‘Ma,’ he said to Mallika Sengupta, for she was his one confidant, sitting in the car in a traffic jam between Gorbunder Road and Mahim on one of their trips to the city, ‘Salma is beautiful, isn’t she?’ The car had stopped by an old municipal tank it went past almost every day, the railings round it recently painted a garish green.

‘Yes, she is,’ said Mrs Sengupta, not insincerely, but only half-attentive, as if this conversation couldn’t, of course, lead to anything serious.

‘Don’t you think,’ he hesitated only for an instant, ‘that she’d make a very good wife? I mean, generally speaking, I’d be happy with a wife like that.’

Ah, the future! It was a time when Nirmalya could say anything he wanted about it; he had a magical, careless sense of abandon about the future. And words had begun to come easily to him; he’d just begun to discover he could express any desire, voice any wish.

‘Why,’ said his mother, amused and assured rather than scandalised, as if she knew better than he that this was another of his daydreams, except that now, unlike before, he was at the brink of that age when he could almost turn his daydreams into the life that he, and, by extension, they, would live, ‘will you carry her away on your white horse?’

Nirmalya looked out of the window to avoid further charges of silliness.

‘Such things don’t happen in real life,’ she said, not cruelly, perhaps with a tinge of concern, looking straight ahead as the car began to move. ‘It isn’t possible.’

What, then, is possible? He saw himself on a horse, galloping down the curve of Carter Road toward Juhu Danda, and dismissed the idea at least temporarily with a wry smile. Not only books and stories, but real life too has its own verisimilitude against which we keep comparing ourselves. He was bound not by social strictures — in the end, he could not be — but by a sense of plausibility that hung over everything, visible and invisible, and which he came up against daily — not like a wall, but a gentle undefinable limit, circumscribing his new adult life; his feelings for Salma would probably come to nothing, he knew, but not because they were socially inadmissable; the sense of plausibility, pervasive in everyday existence as the conventions of narrative are to a story, curtailed what, after all, might otherwise have been possible, and pleasing.

Then, as suddenly and inexplicably as Anju had first appeared that day in their new flat, they stopped coming — the quiet, beautiful daughter, whom he’d toyed with the idea of falling in love with, and the woman who’d scooped Nirmalya to safety just as he was about to fall. Maybe something had happened; maybe nothing had — maybe somebody had moved out; or hadn’t. The Senguptas didn’t know; but they stopped coming.

Before that, however, Anju visited them once in the afternoon.

‘She had a shooting in Simla, memsaab,’ she said, lowering herself on the carpet before the bed with a mixture of docility and an old bone-tiredness. ‘Chunky Pandey is in the film. See.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.