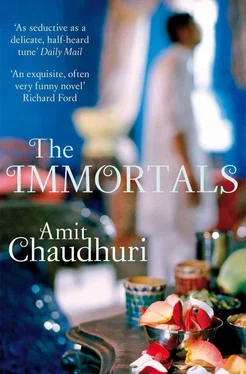

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But there wasn’t a place for everything that had left the big company apartment, and some of it found its way to other places. The large green carpet, for instance, had, alas, to be snipped; it was much too big for a drawing room of this size. The snipped bit had swiftly become a rug in Shyamji’s flat: welcomed and appropriated there with much delight, with nodding assent at the rightness and inevitability of this transfer, and of course gratitude. Two chairs and a low Sankhera table also quietly travelled there, and an old cupboard had been claimed shyly but impetuously one day by Shyamji’s younger brother Banwari (‘Didi, what about us?’ he’d said at last after a sitting, frowning, mock-offended, like a child trying to charm an elder: ‘Everything goes to Shyam bhaiyya.’).

When Mrs Sengupta went to visit Shyamji in his flat (it was easier to do so now; the anonymous but impatient developments of Versova weren’t too far from Pali Hill), she encountered the snipped-off bit of carpet, not recognising it for a moment, but feeling an odd proprietorial affinity toward it. Severed from its previous expanse, it had merged with and made a home of its present surroundings, a small table stacked with pans looming above it on the left and the detached rectangle of the first-floor veranda opening on to twilight not far from it; once she remembered where it had come from, it gave up its subterfuge and she was buoyant and was translated into a mood of mischief on seeing it. ‘Arrey, isn’t this my carpet?’ she squinted. The others nodded vigorously at the sensibleness of this query, as if they were just trying to take care of certain things that had been entrusted to them. And there were the two chairs, and the pretty low table with the glass top and the rounded, fluted wooden legs she’d bought years ago from Gurjari. ‘They are looking nice,’ she said, so distant a judgement that it was removed from, at once, irony and literal truth.

‘Didi,’ said Sumati, Shyamji’s wife, ‘do sit down,’ and led her to one of her ‘own’ chairs.

Notwithstanding these gifts, there had been a slight cooling in relations between the Senguptas and Shyamji. The old grievance, that Shyamji hadn’t really been serious about enhancing Mrs Sengupta’s prospects as a singer, that he’d never really taken her talent in hand, returned: ‘After all, what exactly is he doing for you that he isn’t for all the others?’ Nirmalya demanded of Mallika Sengupta, long-haired, immovable, angry. An irritability about the constant ritual of singing-lessons going nowhere from ever since he could remember, from when he was a boy in the flat in Cumballa Hill, trespassing quietly into the bedroom while his mother practised the last song she’d been taught sitting on a bed, her harmonium before her, her distant figure and the look of questing, unworldly dedication on her face captured in the dressing-table mirror, song after song by Meera or Tulsidas or Kabir being added to an already teeming ‘stock’ of songs — the pointlessness of his mother’s career as a singer made him brutal. And the relationship between guru and student was complicated by an undertone of suspicion that, after Apurva Sengupta’s retirement, Shyamji, always smooth but with an intuition for sensing in which direction the future lay (for how else could he survive?), would have less time for Mallika Sengupta. That was the natural way of things in Bombay after all; it was one of the mild tremors and shocks of post-retirement life here, even for the very well-to-do, this slow orbiting away of the familiar. ‘His mind is elsewhere. I can feel it,’ complained Mrs Sengupta. ‘He taught me the same song for three sittings, and then he gave me one with a slightly cheap tune. I told him, “Shyamji, yeh gaana mujhe pasand nahi aaya, I didn’t like the song,” and he looked puzzled and irritable and said, “Achha gaana hai didi, it’s a good one.”’

‘Do you know that Laxmi Ratan Shukla is dead?’ said Mr Sengupta, faintly disbelieving (as he always was, afresh, on being told that someone had died) but smiling wryly, as if the reason for a particularly long and tiring wait had been finally disclosed to him; he’d just returned from his journey to the city; with his back to his wife, he opened the cupboard and distractedly impaled his jacket upon a hanger.

‘What?’ cried Mallika Sengupta, looking up and waiting for him to turn and to catch his eye. A strange melange of emotions invaded her; among them was the instinctive realisation that a person’s dying was such a simple solution to so many dilemmas and hesitancies, but a solution never seriously considered till it happened and surprised you with its straightforwardness. He’d been Head of the Light Music wing of HMV when he’d died, though he’d been less on her mind than even two years ago; some people never retire, and become fixed to their employment, like a mask. Very few find out, or even care to, what they were outside it.

‘Yes,’ he nodded. ‘Two days ago. Died of a stroke.’

An employee at HMV he’d run into that afternoon in the lobby of the Taj had paused a moment to break the news, as if Laxmi Ratan Shukla had to, in some form, briefly inhabit these bits of formal chit-chat between them. A couple of minutes of astonishment and slow questioning — ‘When?’ ‘How?’ — and nods and grim phrases, and that was it, they continued urgently in opposite directions. And it almost seemed to Mallika Sengupta that a burden had lifted, that she’d been delivered from waiting for the day this man would be persuaded just that little bit more — that final push — and produce her disc; and surely there must be many others, in whose thoughts Laxmi Ratan Shukla had become a dull and persistent discomfort, who’d been similarly delivered. That day — the day Shukla would pick up the phone and say to her husband, ‘Sengupta saab, we will do it now; there is a possibility. .’ or rise from his table to say innocuously, with that discomfiting softness, ‘Sengupta saab, please sit down. .’ and give the go-ahead — that day, it was safe to say, would never come, and she was glad she’d give up, now, whatever attachment she’d had to its arrival.

‘Shyamji,’ she said on the phone, wanting to disabuse him as quickly as possible of any notion he might have had of the man’s continuance in the world, ‘Laxmi Ratan Shukla is no more.’

He replied gravely, unfazed, ‘He never did anyone any good’; the seriousness with which he said this made her laugh later; for her, it became Shukla’s epitaph.

For Mr Sengupta, Shukla’s death was, in passing, a day on which to take stock, to understand what music — especially in its incarnation in his wife, his marriage — had meant to him; although there were several other things, to do with the consultancy he was providing the Germans, to preoccupy him in the evening. Had he been too soft, had he given Shukla too much time of day, as Mallika Sengupta seemed to think; would she have fared better if he’d not depended so heavily on this enigmatic man and acted, in his own eyes, with more recklessness? He laughed to himself, as he entered into an imaginary dialogue — composed of strong and inextricable feelings, not words — with his wife and son upon the subject (when he actually had to talk to them about it, he found himself unable to use any but the simplest generalities, which his son infuriated him by dismissing almost immediately); Mallika had wanted recognition, that pure, woebegone desire for a reward for her gift had accompanied her life from the start but never overwhelmed it; but she hadn’t wanted to dirty her hands in the music world; she’d wanted to preserve the prestige of being, at once, an artist and the wife of a successful executive. She knew, with an uncomplicated honesty, what her worth was; to what extent could she compromise or to which level stoop if others pretended not to? She kept her distance; remaining busy all the time, not a moment’s hiatus, busy with the music, busy with the household, busy with Nirmalya’s life and Mr Sengupta’s. That had left him with no choice but to pursue Shukla, who’d been more than happy, in his phlegmatic way — if ‘happy’ was a word you could use of him — to be pursued. Apurva Sengupta hadn’t liked pursuing Shukla; sometimes, he’d found it perplexing and pointless — as a human being, but also as a manager of people and departments. The pursuit had ended; the quarry — though it was Mallika Sengupta who felt more like a quarry herself — had suddenly removed itself, permanently.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.