Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

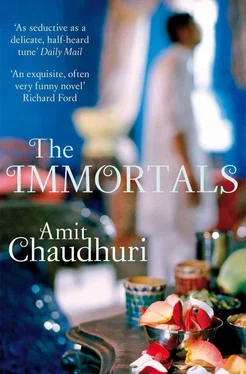

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Also, the blood sugar is high,’ he admitted shame-facedly, delicately lifting his kurta as he lowered himself on to the carpet; he always felt contrite when what he saw to be the superstitions of the educated about health — listen to what the doctor tells you, take your pills, do nothing in excess — when these superstitions proved right, and his own belief, his unspoken but absolute taking for granted of the fact that the supernatural would look out for him (a pale orange thread from a baba, a sort of supplement or insurance policy, was tied round his wrist) seemed, for some reason, not to have worked, at least not this time. Besides (and he didn’t elaborate on this to Mrs Sengupta), he’d been meeting families visiting Sagar Apartments to congratulate him and Sumati for the birth of their second grandson — born to their elder daughter in Delhi in May; how not to finish the rich red swirl of gajar ka halwa on the plate when you were thinking of your own flesh and blood?

‘Shyamji!’ she admonished him. ‘You’ve been eating sweets. Really, you people are so careless!’ It wasn’t clear whom she meant by ‘you people’ — his family, or a wider category of the similarly blithe and faithful. But she took it up with Sumati when she saw her floating prevaricatingly in their flat in Sagar Apartments.

‘Didi, look what’s happened to your brother!’ said Sumati, in mock consternation, as if discussing a wayward but absorbing child.

‘Really, you must take this more seriously,’ said Mallika Sengupta, small but firm, trying to puncture Sumati’s spontaneous attempts to inject levity into the everyday problems of existence. ‘He must take his medicines. And he must stop eating sweets. Jalebis and milk — nothing seems less appetising.’

‘Don’t worry, didi,’ she replied, ‘I am going to become like Hitler’; and she became erect, her bangles shook as she drew her aanchal around her and adopted a stern posture, approximating the fierce man, the tiny moustache and the manic disciplinarianism.

‘Take him to Dr Samaddar,’ said Mrs Sengupta. ‘See what he says.’

A leading cardiologist on Peddar Road, ensconced in his chamber and standing up and looking out moodily, between receiving patients, at the traffic. She did not like thinking of him; six months ago, he’d examined Nirmalya, distant, avian, circling round him and zeroing in with his stethoscope.

Dr Samaddar’s ‘chamber’ was not far, in fact, from where Motilalji lived — Motilalji, Sumati’s elder brother, who’d taught Mrs Sengupta and, that morning many years ago, a bit hazy, for him, with alcohol, introduced Shyamji to her.

Sunil Samaddar was a disconcertingly quiet man. Dealing with people who believed he could perform miracles but didn’t really listen to him had, to all appearances, tired him and left him largely immune to the unexpected; the great and undisappointingly regular amounts of money he earned each day from speaking the truth had probably made him a little cold.

He made Nirmalya, who loved to go on unhappy, poetic walks, but almost never ran, take the treadmill test; surprised into chasing something that was unattainable, in fact, nameless, the boy embarked on the run silent and unquestioning, stoic in his obscure errand; then, like a young soldier who’s unsure of having already outlived his usefulness, he was stripped waist upward, led to one side of a room, and attached to an ECG, and then to the strange gulps and grunts of an echocardiogram; the gulps and grunts, Nirmalya realised (though Dr Samaddar, hovering in his precise steel-framed spectacles, was ironical and taciturnly remonstrative as a teacher in a school), of his heart.

Seeing her son in this way, gleaming dully next to the machine, brought Mallika Sengupta close to tears; but she couldn’t look away. All his promise was reduced to that thinness.

When the family of the Senguptas had recomposed itself before the doctor’s table, he said with the clipped, ironical finality he seemed to say everything: ‘He’ll need to have an operation.’

They’d heard this before, but each time it thoroughly unsettled Apurva and Mallika Sengupta. Without moving an inch, they drew together silently, like a couple suddenly confronted with oncoming bad weather.

‘What kind of operation?’ asked Mr Sengupta, his corporate self-possession not so easily humbled; there was hope until the doctor became more specific.

Dr Samaddar, looking in a rehearsed way at the notepad before him, spoke casually, as if he were reading out the name of a common commercial product:

‘Open-heart surgery, of course. They’re a dime a dozen these days.’

Again, silence, and shock; as with all taboos, it was the temerity of mentioning it in what was almost approaching a social conversation that was more outrageous and unforgivable than the taboo itself.

‘Does he have to be operated on straight away?’ asked Mallika Sengupta, her eyes brimming in wordless reproach, but deliberately making her question an absurd one, and unanswerable in the affirmative. The doctor, though, was on to her game; dryly, he replied, barely tolerant of the nuisance that human emotions represented:

‘Well, not straight away; I don’t know what you mean by “straight away” — but there’s no getting around it. Better sooner than later. Shubhashya shigram. “Haste is auspicious.” By forty, he’ll have to be operated upon.’

Forty, again, that magic number — it was as if a demon had begun to materialise, and had melted before it could become fully visible! Nirmalya’s parents relaxed imperceptibly, without feeling any happier. But, by the time Nirmalya was forty, all sorts of new technologies would have sprung into existence, open-heart surgery would become obsolete (as they’d been hoping it would for almost twenty years now), like the 78 rpm record and ether (they had witnessed the demise of both), perhaps something as simple as a pill or an intravenous tube would perform the rescue and repair work, travelling like an emissary through the blood, as catheters did these days while performing more minor missions, and the heart, the human heart, would be released from its long history into new possibilities.

‘No, they won’t touch him,’ said Apurva Sengupta grimly as they drove down the slope of Peddar Road towards Haji Ali, past the Cadbury’s building, which had stood there, incontrovertibly promising sweetness and the white goodness of a glass of milk a day, ever since they’d first arrived in Bombay — Nirmalya, sitting within earshot in the front of the car, absent-minded and calm, as if they were talking about someone else; a cousin or a twin. Neither livelihood nor life was as yet his concern; he still had, glancing from glinting windshield to dashboard to window to the vistas they were quickly passing, the freedom of his moods and startling intimations. Apurva Sengupta, though, spoke not just from paternal emotion, but from the authority of having been a successful man, of having his views listened to, of having run a large company, of knowing a thing or two about the computations that ensured (in conditions that provided little that was helpful or congenial) a company’s longevity. He adjusted the knot of his tie irritably, full of a long-standing and ingrained certainty. He may have retired, but being an executive, a man in charge of other men, for so many years had given Apurva Sengupta a sense of conviction and moral weight.

Dr Samaddar’s examination of Shyamji was brief. Looking hesitant and politely suspicious, as if he wasn’t sure (like a man who’s been given enthusiastic but indecipherable street directions) that he’d arrived at the right place, Shyamji had entered the air-conditioned room with Mr Sengupta. There he was, only partly at ease with the distinguished man in the black suit and neat striped tie who smelled pleasantly of aftershave. Dr Samaddar regarded them speculatively.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.