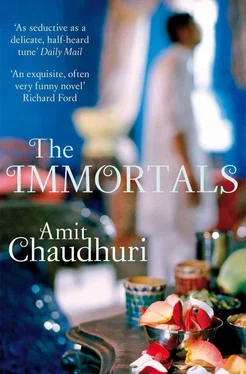

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Life is a longing for betterment: in that sense, Shyamji was very much alive; he’d sold the second-hand Fiat, but he wanted another car now, one that wouldn’t stop and start in bursts and would lift him from his recent, expensive dependence on autos and taxis. But, even at home, suddenly drained of energy and interest, he sometimes lay on his side when teaching a young man who might have journeyed all the way from Marine Lines, the perspiration and heat of the city surrounding him like a nagging but, for the present, bygone impediment, Shyamji propped patiently on an elbow, studying the young arrival with concern, cheek resting against the palm of a hand. He managed to sing from this almost horizontal position, crushing the pillow with his elbow, and kept time by snapping his fingers; of course, Ram Lal’s stern portrait, which had moved from King’s Circle to Borivli to, now, the wall on the left, the same rose-backgrounded picture that was garlanded and placed at a respectful angle on the stage during the Gandharva Sammelans — the face in this portrait seemed unable to comprehend so much movement, all this recent burgeoning of possibility and material well-being, and the vaguely familiar figure of the sick man, and it seemed to have resigned itself to its location, where it was indispensable, but essentially unnoticed. ‘Theek hai, let’s go over it again,’ the recumbent Shyamji would sigh at last to the shy, obedient man sitting erect before him. Oddly, disconcertingly, he felt perfectly well when he sang, and this made him briefly doubt both his and everyone else’s judgement; something to do with the miracle of song and its pleasure, which, whatever the context, seemed to recognise neither age nor fatigue nor disease, but only its complete union with, and absolute necessity to, the world.

Nirmalya went to him one month before leaving for London, when he was in a state at once valedictory and dutiful and strangely distracted; he kept putting off appointments with Shyamji, but one morning set out without explanation in the Ambassador, a new, inarticulate driver at the wheel, Nirmalya placing, with a mixture of self-consciousness and ironic abandon, the Panasonic two-in-one beside him at the back. His mission was to tape some new compositions and ragas from his guru, to take them with him to the faraway but not entirely unfamiliar country he’d be flying to — something he could practise with for the next eight or nine months, after which he hoped to return home for his vacations. None of this was going to be necessarily spelt out to Shyamji; but clearly this was what was on Nirmalya’s mind. It had rained earlier; and the tyres made a minute grinding noise as the car entered the environs of Sagar Apartments, the not quite pukka driveway moist and red and dark, the rubble and bricks of nascent construction projects piled randomly in heaps on its borders. It was rumoured that Rajesh Khanna had booked a property in one of these forthcoming constructions; and though Rajesh Khanna was no longer the kurta-wearing, head-flicking, cherry-lipped beau he once used to be, this piece of unconfirmed information had still raised the esteem of Sagar Apartments in the eyes of Shyamji’s family and others. Walking into the flat, Nirmalya found Shyamji with a handsome young ghazal singer in a flowery shirt; he was called Abhijit, a man of some, but not great, talent, who was trying desperately to get a break as a playback singer in films.

‘Shyamji,’ Nirmalya said shyly when there was, at last, a pause in the proceedings, ‘I want to tape some new compositions.’ And he angled the Panasonic like an awkward object between himself and the harmonium.

‘Do you have Shankara?’ asked Shyamji, running his hands through his oiled hair, expansive and grand at this change of register from the common or garden ghazal he’d been teaching to the rarely-visited, flamboyant raga; and when the boy shook his head, he said almost with a kind of glee, ‘Theek hai, I’ll give you a composition in Shankara. But you’ll have to practise hard to get it right.’ And as an afterthought, ‘I’ll also give you Adana. You don’t have Adana, do you?’ Then, with a look of minor incredulity and puzzlement, as if he’d only just remembered, he asked with a child’s ingenuousness: ‘Baba, when are you leaving?’

‘On the twenty-eighth of next month,’ hummed Nirmalya, shy, holding back, always nervous, in company, of being listened to and noticed.

But Abhijit had, with a disarming matter-of-factness, switched off from the rather highbrow conversation about ragas and international travel, and was crooning a ghazal — not the one he’d just been learning; another one — in an undertone. He was obviously profligate with songs. He was respectfully uninterested in classical music; let the knowledgeable pursue knowledge; what he was after was, simply, melody and success. Someone had told him that his name itself, ‘Abhijit’, had the right sound and weight, the potential to be put into popular circulation; and he now had a quiet faith in his name, and said it undemonstratively but significantly when someone asked him what it was. Glancing once or twice in the direction of the teacher in his vest and the tongue-tied but clearly eager young man, whom he’d met in this flat a couple of times before, he noted with knowing amusement Nirmalya’s shabby clothes, already perfectly aware that Nirmalya was a ‘big officer’s son; Abhijit himself was, of course, always particular about the shirts he wore, and looked quite the hero. Nirmalya, though, was so unremarkably turned out and unprepossessing that it became impossible not to notice him. As he sat down on a chair Abhijit laughed and said:

‘Look how simply he dresses!’ and shook his head almost fondly — because Nirmalya was wearing a kurta that was torn near the pocket. It was a kurta Nirmalya felt comfortable in, for the last four or five years now he’d been inhabiting some of his clothes as if they were something between skin and makeshift private territory, so close was he to them that he became unaware of their fading materiality, they faded into him, almost — he was now in a kurta that he’d worn, as usual, too often.

Shyamji nodded briskly, and murmured, while positioning the tape recorder away from the bellows of the harmonium and before him, ‘Woh sant hai’ — invoking the old word, which was used of saints and poets and the mad or unworldly. Abhijit smiled; he had light cat-like eyes, and they gleamed in pleasure and in crystalline agreement. Shyamji wasn’t mocking Nirmalya; ‘Is the tape in place?’ he asked, almost woeful, looking up from the mysterious, stealthy window of the TDK cassette. He found Nirmalya odd, and his disdain of the whirl and glitter of the city a bit tiresome. He hadn’t been able to understand it. He couldn’t quite see why the boy had to make it a point to head in a direction quite different from the world he’d been fortunate enough to be born into; it was childishness, that’s what it was: once or twice, he’d wanted to say to him, Why, baba, aren’t your parents good enough for you? Isn’t what they gave you good enough? And to add in a tone of guidance and patience, Be happy, baba, that you’re blessed with what you have. But in the last two or three months, he’d become strangely indulgent towards the boy; and, though he hardly thought about it or spent time comprehending it, something about him moved Shyamji against his will. There had been a loosening within, a gradual breaking down of a barrier that had circumscribed, without Shyam Lal even knowing it, everything he’d done; and this change, this forgiving erosion, had expressed itself in his sudden urge to give to the boy whatever compositions he demanded so quietly but insistently, set to these magnificent, ever-returning ragas, ragas you thought you could do without for the time being, but which had a way of coming back to you, the compositions his father had once created and dazzled his listeners with, and which Shyamji imparted to his students with the utmost evasiveness and pusillanimity.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.