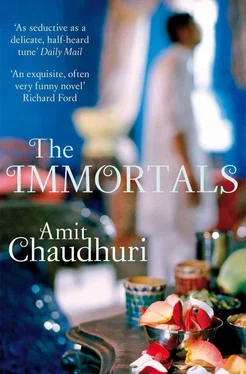

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

* * *

TWO DAYS AFTER he’d left, Shyamji came to the Senguptas’ flat. The curtains were parted to let in the hot, bright light of early October.

‘What, has baba gone?’ he asked, looking slowly around him, as if the boy just might materialise from behind the furniture.

Although he was so dark, his face was pale and scourged this morning, as if he’d powdered it; his feet, beneath his pyjamas, seemed to be swollen. He hobbled comically into the sitting room scattered with curios and pristine ashtrays.

‘Oh, he reached there day before yesterday,’ Mallika Sengupta said — it was almost an announcement; not just for Shyamji, but for the world, if it cared to listen. ‘We spoke for a short while on the telephone. .’. She went into a momentary reverie. ‘The flat is so quiet now.’ Bleary-eyed, she asked — for her sleep had gone awry ever since she’d waited, in the airport, for Nirmalya to be airborne at three in the morning; she’d woken up yesterday and today at half past three, her mind on fire as she wondered where her son would be twenty years from now, eyes shut, determined not to notice the dawn stealthily coming to the windows — ‘Shyamji, will you have some tea before we start?’

Shyamji, who looked like he hadn’t been sleeping too well himself, his cheeks puffy, frowned as if he’d been challenged and said: ‘Why not, didi?’

So cups, trembling faintly, and the pot and strainer were brought to the sitting room on a wooden tray, and they sat, at eleven o’clock in the morning, the mother, sombre with reminiscence, and her teacher, drinking tea without any milk in it, each cup made wonderfully palatable with a sachet of Equal.

‘You know, he said to me on the phone day before yesterday, “Tell Shyamji to be careful. He isn’t looking too well.” ’

Shyamji sipped his tea, smiled ruefully: ‘He is my biggest critic. He keeps a stern eye on me.’

It was true; had been true in the last four years, with those recurrent queries made in the glassy whirl of life in Cuffe Parade. Nirmalya’s frequent, awkward questions to Shyamji — ‘Why don’t you sing more classical?’ — his high-minded disenchantment, from the transcendent vantage-point of Thacker Towers, with the music scene — ‘Why are bhajans and ghazals sung in this cheap way these days?’ — had earned him a nickname, ‘the critic’. It was a bit of leg-pulling; Nirmalya enjoyed it. ‘Baba is a big critic,’ Shyamji would say, pretending to be very thoughtful. And yet Nirmalya, in this incarnation, had managed to make him slightly uneasy. A couple of years ago, late one morning in Thacker Towers, the boy, with obviously no real anxieties to plague him, had asked, genuinely exercised, ‘Why don’t you sing classical more often?’ and Shyamji had tried explaining, with a patience he reserved for the pure-hearted but naive, ‘Baba, you cannot practise art on an empty stomach. Let me make enough money from these lighter forms; and then I’ll be able to devote myself entirely to classical.’ A perfectly workable blueprint. But, to Shyamji’s discomfort, ‘the critic’ had not replied, but looked at him beady-eyed, as if to say, with a seventeen-year-old’s moral simplicity and fierce dogmatic conviction: ‘That moment will never come. The moment to give yourself to your art is now.’

* * *

JUMNA — THIS WOMAN who’d come to their house seventeen years ago as a cleaner of bathrooms, elegant, measured, twenty-six, whom Mrs Sengupta, in the first flush of company life, had pronounced a ‘cultured woman, more cultured than the women I meet at parties’ — this Jumna, already tired and resigned before she’d touched the jhadu, sat down on her haunches on the sitting-room carpet. One small eye sparkled with moisture. She’d been coming late every day for a month, the ends of her sari trailing behind her as she swept guiltily in like a phantom at eleven o’clock; Mrs Sengupta was not happy with her.

‘Memsaab,’ said Jumna, trying to reason with this familiar person shaking her head who was part employer, part perhaps comrade, ‘it’s too long a distance from Mahalaxmi to this part of the city. Bahut vanda hota hai — too much hassle. Why cause all this gichir-michir and gussa? Let me retire now, memsaab.’

Her hair was all grey, the metal strands falling on both sides of the parting and gathered at the back — this woman to whom Mallika Sengupta often used to turn, in the sea-facing heaven of La Terrasse, for solace, of whom she used to think, ‘Well, in some ways she’s luckier than I am.’

She sat before her on her haunches, patient in her campaign.

‘What are you saying, Jumna,’ said Mrs Sengupta, hardly listening. ‘How can you give up a good job in this way? Do you think they’re to be plucked from trees? And you’re much younger than I am.’

She said this complacent in the knowledge that she looked so much younger than Jumna; time hadn’t hurt her substantially since the flash had gone off in the studio in 1971 and illuminated that face with two surreptitious pearl-like crooked teeth and the fashionable dangling earrings falling from the earlobes; and Jumna (who’d circled that photograph and dusted it many times) knew it was only appropriate that this should be so, knew, without envy, that Mrs Sengupta had been blessed by the powers that governed lives (it was enough, for her, to have come into contact with such a being), and she now indulged, as she always did, Mrs Sengupta’s blitheness. As a rule, the poor age more quickly than the affluent; time, and life, move, for them, at another pace, ‘like a relapse after a long illness’. In fact, Jumna’s eldest son, after joining Jaslok Hospital as a sweeper two years ago — temporary employment, but imminently to be made permanent (‘You must educate your children,’ the ten-year-old Nirmalya, who quailed at the thought of school, once preached to Jumna; but her son had, in a doomed, helpless way, dropped out of his municipal school in the seventh standard) — this son had contracted jaundice and died a year ago. The awful husband — ‘Your sufferings in this birth will probably make your next birth a happy one,’ Nirmalya had instructed her when he was seven — that lame bewda who’d knocked out her teeth and drenched her with kerosene, intent to set fire to her one night: he too had died, hunted down by cirrhosis, two years ago. Now Jumna had had enough of making that tedious journey from Mahalaxmi; her left eyelid closed upon moisture; she wanted to go to the free optician for a pair of long-awaited spectacles.

‘I’ll find employment in the city,’ she reassured her unconvinced employer, and then, like a charm against refusal, reiterated a by-now ancient, barely-respected excuse. ‘The train to Bandra takes long, and sometimes I miss the train.’

* * *

HE KEPT GOING to the window of the little room, almost habituated now to its odd smell of carpet and fittings and the faint hovering ghost of a cigarette smoker; it was a concourse of people he wanted to see, but each time found other windows reflecting the modest light, and a courtyard on which it rained often. From the beginning, he was struck by the excess of silence; and he began to realise that his famous love of solitude was not real, that he loved company and noise much more than his own thoughts. He ate badly; half-eaten green apples, bitten into without pleasure, were thrown into the waste-paper basket; he went into the kitchen like a mouse at three o’clock in the afternoon, when there was no one else there, and put a Ginsters’ Cornish pasty into the oven. It smelled awful; but it was an absurdly, almost cheeringly, simple solution, and the rank but appetising smell made him impatient with hunger; the first bite always burnt his lips. Later, dead with solitariness, he switched on the kettle to make himself a cup of tea, its rumble growing like an approaching storm and chastising him and making him nervous, until the entire room filled with its roar. He needn’t have worried; it became silent, like everything else, including the plumbing behind the walls — where, as a matter of fact, the real pulsations of the place seemed to be hidden. The steam emerging from the spout pleased him; as any signal of life, even from things not really alive, had begun to please him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.