In principle, this translation adheres as closely as possible to the elusive ideal of textual fidelity. Recourse to annotation allows for the possibility of rendering the novel’s rich colloquiality more directly. Though often rendered in approximate equivalents toward the beginning of the translated novel, many of the original lunfardo or Argentine-slang terms, are progressively incorporated in the translated text, with explanations provided in the notes and the glossary; the intent is that readers should gain more direct access to the palpable flavour of a unique urban culture, which in turn facilitates a more precise reading of it. It is worth noting that two of the many dictionaries I consulted — the Academia Argentina de Letras edition of the Diccionario del habla de los argentinos and José Gobello’s Nuevo diccionario lunfardo — both frequently cite Marechal’s Adán Buenosayres to illustrate particular Argentine usages; this is yet another indication of the novel’s cultural importance.

The long sentences and elaborate language of Marechal’s neo-Baroque prose present a problem for English syntax. I have broken up run-on sentences when doing so seemed to profit readability, but never at the expense of any layer or nuance of meaning. Marechal’s prose is often self-parodic: he piles up clause after clause in pretentiously elaborate constructions with comic intent, the opulence of the expressive means humorously contrasting with the relative banality of the content. In such cases, I have adjusted the syntax as little as possible, in order to conserve the humour. In cases where language is ludically celebrated in nonsense prose or utterly gratuitous puns, I have at times needed to sacrifice textual fidelity; such instances are signalled in endnotes.

Further, in order to retain as much original flavour as possible, I have, with two exceptions, not translated the characters’ names. The first is the most vexatious; the eponymous “Adán Buenosayres” — in Spanish a euphonious six-syllable verse of poetry — has been rendered as “Adam Buenosayres.” Unfortunately, the substitution disrupts the rhythm of the name/title, and the music of this lovely verso llano suffers. However, the name Adán is not readily recognizable to most anglophones, and would not therefore convey all the biblical and symbolic freight we hear in “Adam.” Poetry has thus had to take second place to meaning. The other exception is the name of the astrologer Schultz, changed from Marechal’s “Schultze,” the latter being a far less common form of the German surname. But the real-life model for the astrologer is the self-named Xul Solar, a monniker that condenses his birth name “Oscar Agustín Alejandro Schulz Solari.” It seems likely that Marechal preferred “Schultze” because the German “Schulz,” lacking the final voiced “e”, is virtually unpronounceable within the phonological system of Spanish. In English, by contrast, it is more natural to say Schultz and to spell it with a “t” (as Marechal has done).

Much lyric material is quoted in the novel, including verses from tangos, folk songs, children’s poetry, doggerel, and Marechal’s own poetry. So as not to disrupt the flow, I have placed my translations of this material in the main text and the original versions in the endnotes. Readers of Ulysses will notice that I use the same protocols for dialogue as Joyce does; that is, a dash to mark the point where a given character’s speech begins. This partially replicates the Spanish punctuation observed in Marechal’s text (in Spanish, a second dash normally marks the point where the speech act ends). In fact, as Lafforgue notes, Marechal in his manuscript notebooks often neglected to add the closing dash (“Estudio filológico preliminar” xxiii — xxiv), perhaps unconsciously under the influence of his reading of Ulysses . On the other hand, as Barcia observes (103), Marechal never used the Joycean stream-of-consciousness technique. Indeed, he seems to hesitate when punctuating complex narratorial layering; in Book Two, chapter 1, for example, he vacillates between the dash and quotation marks when handling Adam’s interior monologues, sometimes presenting them as soliloquies (see Lafforgue and Colla’s critical edition). Nevertheless, once in print, the punctuation remains quite stable in all succeeding editions. In this translation, with the exception noted above, I reproduce Marechal’s punctuation of dialogue and interior monologue.

Marechal often cites classical phrases in Latin. Unless the phrase is very short and its meaning obvious, I usually provide translations in the notes. When we read, for example, that Adam says something to himself ad intra , it is obvious that he is speaking inwardly. Adam’s penchant for using Latin phrases, an anti-modernist gesture, is as odd in Spanish as it is in English. The narrator uses phrases from both classical and medieval Church Latin, often with cheeky jocularity.

The annotation, intended for both scholars and non-specialist anglophone readers, owes much to Pedro Luis Barcia’s 1994 edition, as well as to the recent critical edition of Javier de Navascués, who was kind enough to exchange manuscript notes with me. References to Barcia’s notes are indicated by page number (e.g., Barcia 100n); likewise to Navascués’s critical edition (e.g., Navascués, AB 227n). Textual material quoted in the notes, if the original is in Spanish prose, is rendered in my English translation, unless otherwise indicated. All errors and omissions, of course, are entirely my responsibility.

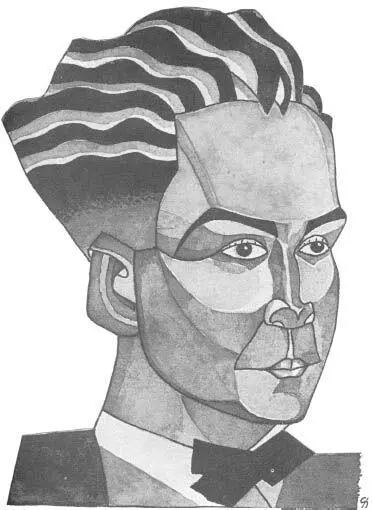

Leopoldo Marechal in 1929. (Courtesy of María de los Ángeles Marechal)

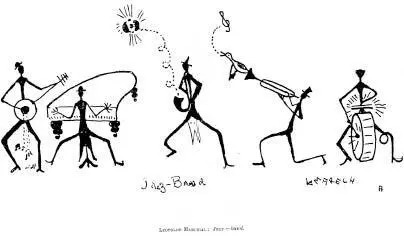

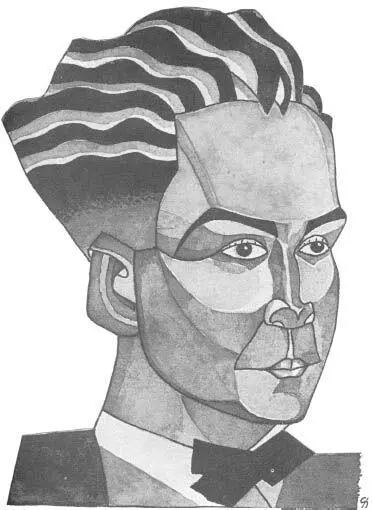

Sketch of Marechal from mid- to late 1920s. (Artist unknown, often attributed mistakenly to Xul Solar)

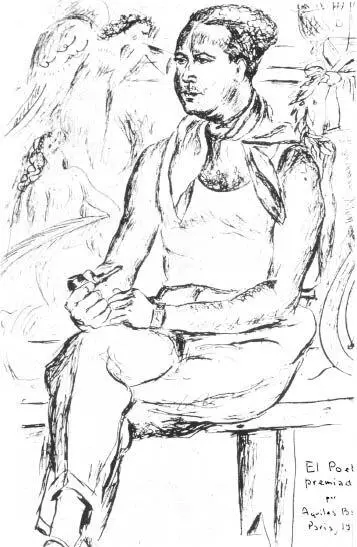

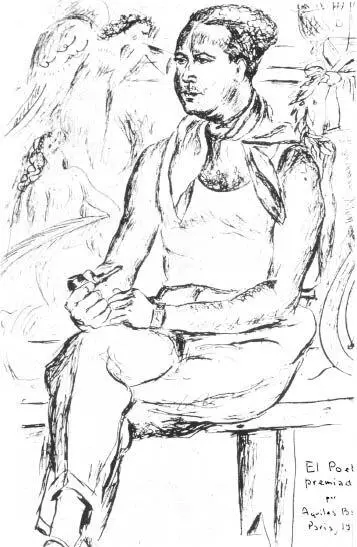

Sketch of Marechal by Aquiles Badi (Paris, 1930). (Courtesy of María de los Ángeles Marechal)

Argentine artists of the “Grupo de París” around Aristide Maillol’s Monument à Cézanne in the Jardin des Tuileries, Paris, 1930. Standing, left to right: Juan del Prete, Alberto Morera, Horacio Butler, Raquel Forner, Leopoldo Marechal. Sitting, left to right: Maurice Mazo, Alfredo Bigatti, Athanase Apartis. (Courtesy of the Fundación Forner-Bigatti)

Artists of the “Grupo de París” in Sanary-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, 1930. Left to right: Alberto Morera, Alfredo Bigatti, Aquiles Badi, Leopoldo Marechal, Raquel Forner, Horacio Butler. (Courtesy of the Fundación Forner-Bigatti through the Centro Virtual de Arte Argentino)

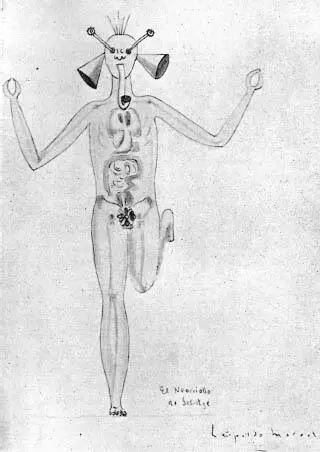

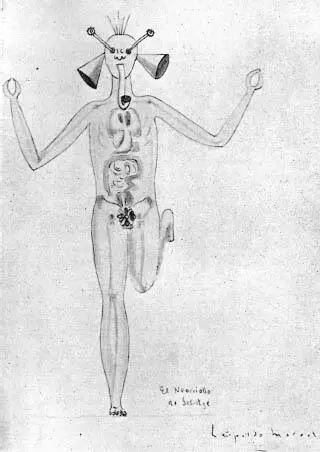

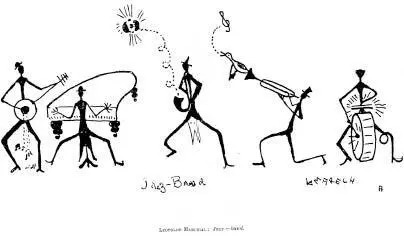

Marechal’s working sketch of Schultz’s “Neocriollo,” the astrologer’s visionary model of Argentina’s future inhabitants. (Courtesy of María de los Ángeles Marechal)

Читать дальше