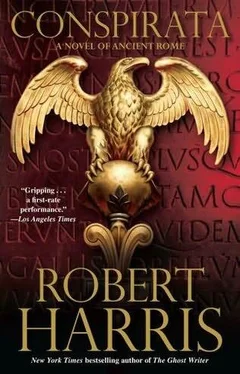

Robert Harris - Lustrum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Harris - Lustrum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lustrum

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lustrum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lustrum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lustrum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lustrum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Why should I be worried? He got what he wanted, all except the command of an army to destroy Catilina – that he should even have thought of asking for that amazed me! But as for the rest – those letters Sositheus wrote at my dictation and left on his doorstep were a gift from the gods as far as he was concerned. He cut himself free of the conspiracy and left me to clear up the mess and stop Pompey from intervening. In fact I should say Crassus derived far more benefit from the whole affair than I did. The only ones who suffered were the guilty.'

'But what if he makes it public?'

'If he does, I'll deny it – he has no proof. But he won't. The last thing he wants is to open up that whole stinking pit of bones.' He picked up his book again. 'Go and put a coin in the mouth of our dear dead friend, and let us hope he finds more honesty on that side of the eternal river than exists on this.'

I did as he commanded, and the following day Sositheus's body was burnt on the Esquiline Field. Most of the household turned out to pay their respects, and I spent Cicero's money very freely on flowers and flautists and incense. All in all it was as well done as these occasions ever can be: you would have thought we were bidding farewell to a freedman, or even a citizen. Thinking over what I had learned, I did not presume to judge Cicero for the morality of his action, nor did I feel much wounded pride that he had been unwilling to trust me. But I did fear that Crassus would try to seek revenge, and as the thick black smoke rose from the pyre to merge with the low clouds rolling in from the east, I felt full of apprehension.

Pompey approached the city on the Ides of January. The day before he was due, Cicero received an invitation to attend upon the imperator at the Villa Publica, which was then the government's official guest house. It was respectfully phrased. He could think of no reason not to accept. To have refused would have been seen as a snub. 'Nevertheless,' he confided to me as his valet dressed him the next morning, 'I cannot help feeling like a subject being summoned out to greet a conqueror, rather than a partner in the affairs of state arranging to meet another on equal terms.'

By the time we reached the Field of Mars, thousands of citizens were already straining for a glimpse of their hero, who was now rumoured to be only a mile or two away. I could see that Cicero was slightly put out by the fact that for once the crowds all had their backs to him and paid him no attention, and when we went into the Villa Publica his dignity received another blow. He had assumed he was going to meet Pompey privately, but instead he discovered several other senators with their attendants already waiting, including the new consuls, Pupius Piso and Valerius Messalla. The room was gloomy and cold, in that way of official buildings that are little used, and yet although it smelled strongly of damp, no one had troubled to light a fire. Here Cicero was obliged to settle down to wait on a hard gilt chair, making stiff conversation with Pupius, a taciturn lieutenant of Pompey's whom he had known for many years and did not like.

After about an hour, the noise of the crowd began to grow and I realised that Pompey must have come into view. Soon the racket was so intimidating the senators gave up trying to talk and sat mute, like strangers thrown together by chance while seeking shelter from a thunderstorm. People ran to and fro outside, and cried and cheered. A trumpet sounded. Eventually we heard the clump of boots filling the antechamber next door, and a man said, 'Well, you can't say the people of Rome don't love you, Imperator!' And then Pompey's booming voice could be heard clearly in reply: 'Yes, that went well enough. That certainly went well enough.'

Cicero rose along with the other senators, and a moment later into the room strode the great general, in full uniform of scarlet cloak and glittering bronze breastplate on which was carved a sun spreading its rays. He handed his plumed helmet to an aide as his officers and lictors poured in behind him. His hair was as improbably thick as ever and he ran his meaty fingers through it, pushing it back in the familiar cresting wave that peaked above his broad, sunburnt face. He had changed little in six years except to have become – if such a thing were possible – even more physically imposing. His torso was immense. He shook hands with the consuls and the other senators, and exchanged a few words with each, while Cicero looked on awkwardly. Finally he moved on to my master. 'Marcus Tullius!' he exclaimed. Taking a step backwards, he appraised Cicero carefully, gesturing in mock-wonder first at his polished red shoes and then up the crisp lines of his purple-bordered toga to his neatly trimmed hair. 'You look very well. Come then,' he said, beckoning him closer, 'let me embrace the man but for whom I would have no country left to return to!' He flung his arms around Cicero, crushing him to his breastplate in a hug, and winked at us over his shoulder. 'I know that must be true, because it's what he keeps on telling me!' Everyone laughed, and Cicero tried to join in. But Pompey's clasp had squeezed all the air out of him, and he could only manage a mirthless wheeze. 'Well, gentlemen,' continued Pompey, beaming around the room, 'shall we sit?'

A large chair was carried in for the imperator and he settled himself into it. An ivory pointer was placed in his hand. A carpet was unrolled at his feet into which was woven a map of the East, and as the senators gazed down, he began gesturing at it to illustrate his achievements. I made some notes as he talked, and afterwards Cicero spent a long while studying them with an expression of disbelief. In the course of his campaign, Pompey claimed to have captured one thousand fortifications, nine hundred cities, and fourteen entire countries, including Syria, Palestine, Arabia, Mesopotamia and Judaea. The pointer flourished again. He had established no fewer than thirty-nine new cities, only three of which he had allowed to name themselves Pompeiopolis. He had levied a property tax on the East that would increase the annual revenues of Rome by two thirds. From his personal funds he proposed to make an immediate donation to the treasury of two hundred million sesterces. 'I have doubled the size of our empire, gentlemen. Rome's frontier now stands on the Red Sea.'

Even as I was writing this down, I was struck by the singular tone in which Pompey gave his account. He spoke throughout of 'my' this and 'my' that. But were all these states and cities, and these vast amounts of money, really his, or were they Rome's?

'I shall require a retrospective bill to legalise all this, of course,' he concluded.

There was a pause. Cicero, who had just about recovered his breath, raised an eyebrow. 'Really? Just one bill?'

'One bill,' affirmed Pompey, handing his ivory stick to an attendant, 'which need be of just one sentence: “The senate and people of Rome hereby approve all decisions made by Pompey the Great in his settlement of the East.” Naturally, you can add some lines of congratulation if you wish, but that will be the essence of it.'

Cicero glanced at the other senators. None met his gaze. They were happy to let him do the talking. 'And is there anything else you desire?'

'The consulship.'

'When?'

'Next year. A decade after my first. Perfectly legal.'

'But to stand for election you will need to enter the city, which will mean surrendering your imperium. And surely you intend to triumph?'

'Of course. I shall triumph on my birthday, in September.'

'But then how can this be done?'

'Simple. Another bill. One sentence again: “The senate and people of Rome hereby permit Pompey the Great to seek election to the office of consul in absentia.” I hardly need to canvass for the post, I think. People know who I am!' He smiled and looked around him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lustrum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lustrum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lustrum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.