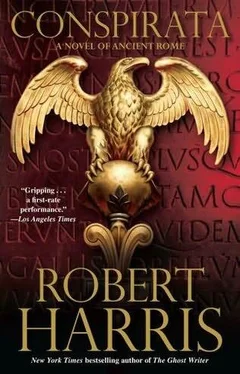

Robert Harris - Lustrum

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Harris - Lustrum» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Историческая проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lustrum

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lustrum: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lustrum»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lustrum — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lustrum», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With that, he set off on the road to Rome, accompanied by only his official escort of lictors and a few close friends. As news of his humble entourage spread, it had the most amazing effect. People had feared he would move north with his army, leaving a swathe of countryside behind them stripped bare as if by locusts. Instead, the Warden of Land and Sea merely ambled along in a leisurely fashion, stopping to rest in country inns, as if he were nothing more grand than a sightseer returning from a foreign holiday. In every town along the route – in Tarentum and in Venusia, across the mountains and down on to the plains of Campania, in Capua and in Minturnae – the crowds turned out to cheer him. Hundreds decided to leave their homes and follow him, and soon the senate was receiving reports that as many as five thousand citizens were on the march with him to Rome.

Cicero read of all this with increasing alarm. His long letter to Pompey was still unacknowledged, and even he was beginning to perceive that his boasting about his consulship might have done him harm. Worse, he now learned from several sources that Pompey had formed a bad impression of Hybrida, having travelled through Macedonia on his journey back to Italy, witnessing at first hand his corruption and incompetence, and that when he reached Rome he would press for the governor's immediate recall. Such a move would threaten Cicero with financial ruin, not least because he had yet to receive a single sesterce from Hybrida. He called me to his library and dictated a long letter to his former colleague: I shall try to protect your back with all my might, provided I do not seem to be throwing my trouble away. But if I find that it gets me no thanks, I shall not let myself be taken for an idiot – even by you. A few days after Saturnalia there was a farewell dinner for Atticus, at the end of which Cicero gave him the letter and asked him to deliver it to Hybrida personally. Atticus swore to discharge this duty the moment he reached Macedonia, and then, amid many tears and embraces, the two best friends said their farewells. It was a source of deep sadness to both men that Quintus had not bothered to come and see him off.

With Atticus gone from the city, worries seemed to press in on Cicero from every side. He was deeply concerned, and I even more so, by the worsening health of his junior secretary, Sositheus. I had trained this lad myself, in Latin grammar, Greek and shorthand, and he had become a much-loved member of the household. He had a melodious voice, which was why Cicero came to rely on him as a reader. He was twenty-six or thereabouts, and slept in a small room next to mine in the cellar. What started as a hacking cough developed into a fever, and Cicero sent his own doctor down to examine him. A course of bleeding did no good; nor did leeches. Cicero was very much affected, and most days he would sit for a while beside the young man's cot, holding a cold wet towel to his burning forehead. I stayed up with Sositheus every night for a week, listening to his rambling nonsense talk and trying to calm him down and persuade him to drink some water.

It is often the case with these dreadful fevers that the final crisis is preceded by a lull. So it was with Sositheus. I remember it very well. It was long past midnight. I was stretched out on a straw mattress beside his cot, huddled against the cold under a blanket and a sheepskin. He had gone very quiet, and in the silence and the dim yellow light cast by the lamp, I nodded off myself. But something woke me, and when I turned, I saw that he was sitting up and staring at me with a look of great terror.

'The letters,' he said.

It was so typical of him to be worried about his work, I nearly wept. 'The letters are taken care of,' I replied. 'Everything is up to date. Go back to sleep now.'

'I copied out the letters.'

'Yes, yes, you copied out the letters. Now go to sleep.' I tried gently to press him back down, but he wriggled beneath my hands. He was nothing but sweat and bone by this time, as feeble as a sparrow. Yet he would not lie still. He was desperate to tell me something.

'Crassus knows it.'

'Of course Crassus knows it.' I spoke soothingly. But then I felt a sudden sense of dread. 'Crassus knows what?'

'The letters.'

'What letters?' Sositheus made no reply. 'You mean the anonymous letters? The ones warning of violence in Rome? You copied those out?' He nodded. 'How does Crassus know?' I whispered.

'I told him.' His fragile claw of a hand scrabbled at my arm. 'Don't be angry.'

'I'm not angry,' I said, wiping the sweat from his forehead. 'He must have frightened you.'

'He said he knew already.'

'You mean he tricked you?'

'I'm so sorry…' He stopped, and gave an immense groan – a terrible noise, for one so frail – and his whole body trembled. His eyelids drooped, then opened wide for one last time, and he gave me such a look as I have never forgotten – there was a whole abyss in those staring eyes – and then he fell back in my arms unconscious. I was horrified by what I saw, I suppose because it was like gazing into the blackest mirror – nothing to see but oblivion – and I realised at that instant that I too would die like Sositheus, childless and leaving behind no trace of my existence. From then on I redoubled my resolve to write down all the history I was witnessing, so that my life might at least have this small purpose.

Sositheus lingered on all through that night, and into the next day, and on the last evening of the year he died. I went at once to tell Cicero.

'The poor boy,' he sighed. 'His death grieves me more than perhaps the loss of a slave should. See to it that his funeral shows the world how much I valued him.' He turned back to his book, then noticed that I was still in the room. 'Well?'

I was in a dilemma. I felt instinctively that Sositheus had imparted a great secret to me, but I could not be absolutely sure if it was true, or merely the ravings of a fevered man. I was also torn between my responsibility to the dead and my duty to the living – to respect my friend's confession, or to warn Cicero? In the end, I chose the latter. 'There's something you should know,' I said. I took out my tablet and read to him Sositheus's dying words, which I had taken the precaution of writing down.

Cicero studied me as I spoke, his chin in his hand, and when I finished, he said, 'I knew I should have asked you to do that copying.'

I had not quite been able to bring myself to believe it until that moment. I struggled to hide my shock. 'And why didn't you?'

He gave me another appraising look. 'Your feelings are bruised?'

'A little.'

'Well, they shouldn't be. It's a compliment to your honesty. You sometimes have too many scruples for the dirty business of politics, Tiro, and I would have found it hard to carry off such a deception under your disapproving gaze. So I had you fooled, then, did I?' He sounded quite proud of himself.

'Yes,' I replied, 'completely,' and he had: when I remembered his apparent surprise on the night Crassus brought the letters round with Scipio and Marcellus, I was forced to marvel at his skills as an actor, if nothing else.

'Well, I regret I had to trick you. However, it seems I didn't trick Old Baldhead – or at least he isn't tricked any longer.' He sighed again. 'Poor Sositheus. Actually, I'm fairly sure I know when Crassus extracted the truth from him. It must have been on the day I sent him over to collect the title deeds to this place.'

'You should have sent me!'

'I would have done but you were out and there was no one else I trusted. How terrified he must have been when that old fox trapped him into confessing! If only he had told me what he'd done – I could have set his mind at rest.'

'But aren't you worried what Crassus might do?'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lustrum»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lustrum» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lustrum» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.