Figure 2.16 A periodontal probe is inserted along the gum lines surrounding each tooth after imaging and rhinoscopy have been completed. Pockets > 1 mm depth in the cat and > 2–3 mm depth in the dog could result in clinically significant nasal disease due to tracking of bacteria up the tooth root into the nasal cavity.

Laryngoscopy can be performed as an isolated procedure or during the preliminary assessment of the airway before a transoral tracheal wash or bronchoscopy. An appropriate anesthetic protocol must be devised that provides a light plane of anesthesia and preserves laryngeal function. While multiple agents are appropriate for use, the key feature is to have spontaneous and vigorous respirations. An assistant is required to identify thoracic inspiratory efforts so that the examiner can insure coordination of laryngeal abduction with inspiration. If the plane of anesthesia is too deep, one to two boluses of doxapram (0.5–1.0 mg/kg) can be used to stimulate respirations (Miller et al. 2002). An accurate laryngeal examination is important because laryngeal dysfunction can be a contributing component to cough in up to 20% of dogs, even when signs of upper airway disease are lacking (Johnson 2016).

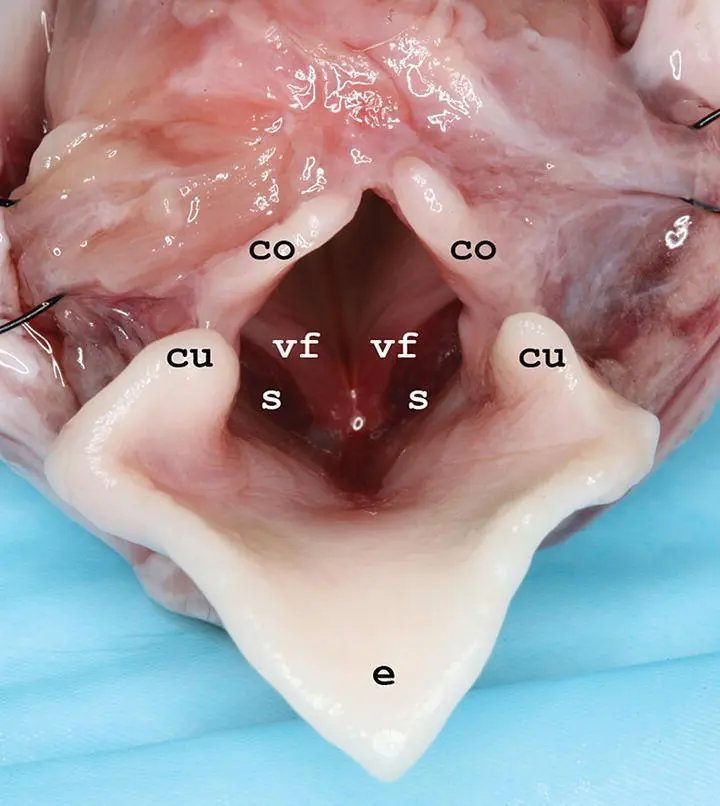

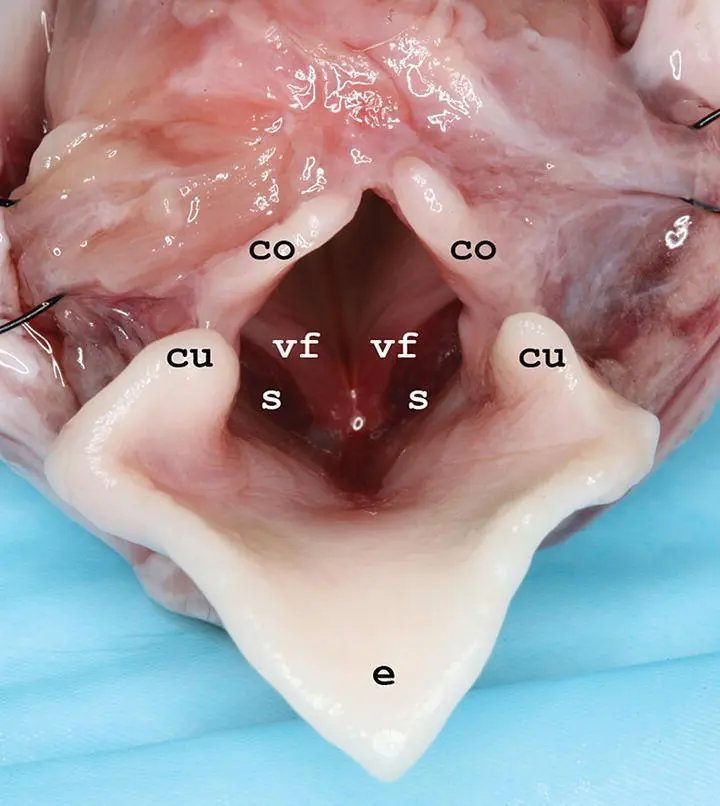

Figure 2.17 Necropsy image of the larynx showing the corniculate processes of the arytenoids (co), vocal folds (vf), cuneiform processes of the arytenoids (cu), saccules (s), and epiglottis (e).

Laryngoscopy includes the assessment of function as well as examination of all structures in the area of the rima glottis, including the soft palate, tonsils, laryngeal aditus, and saccules ( Figure 2.17). The larynx is inspected for edema, hyperemia, or accumulation of secretions, any of which could indicate injury due to turbulent airflow, acid reflux, or lower airway inflammation. Eversion of laryngeal saccules is a common contributor to obstruction to airflow in the upper airways (see Chapter 4). Because they are membranous tissue, saccules are very responsive to manipulation and can become more swollen as the upper airway evaluation continues, so it is important not to over‐interpret this finding. In the normal dog, the soft palate should not overlap with the epiglottis by more than a few millimeters. Tonsils should be within their crypts; enlargement or eversion is suggestive of inflammation or irritation.

Bronchoscopy is one of the most useful techniques for providing a diagnosis in animals with airway or lung disease. It can define the location, grade, and extent of tracheal ring flattening for planning stabilization through surgery or stent implantation, identify protrusion of the dorsal tracheal membrane into the tracheal lumen, document tracheal inflammation or irritation, visualize intrathoracic bronchial or airway collapse, and allow collection of BAL fluid to determine the contribution of small airway disease to respiratory signs. It is also highly useful and successful in managing foreign body inhalation.

Complications that can be encountered after bronchoscopy are worsened cough or increased airway obstruction. These occur most commonly in dogs that have severe tracheal collapse or bronchomalacia, because irritation of the airway potentiates a cough, and suppression of respiratory effort by anesthetic agents allows passive collapse of diseased large and small airways. Excessive stress that induces cough and respiratory distress during recovery is particularly troublesome. Coughing can be partly alleviated by administering dilute lidocaine (approximately 1 ml of 1% lidocaine for a small dog) through the bronchoscope into the trachea at the end of the procedure. Subcutaneous terbutaline (0.01 mg/kg) may improve respirations in dogs with collapsed airways (although it does not act as a bronchodilator in this situation), and recovery in an oxygen‐enriched environment can lessen respiratory distress. Bronchospasm can be a particular problem in the cat with inflammatory airway disease that has severe cough and respiratory distress. Terbutaline should be given subcutaneously immediately prior to the procedure at 0.01 mg/kg to produce airway smooth muscle relaxation and reduce complications. Aerosolized albuterol can be given through the endotracheal tube at the end of the procedure if injectable terbutaline is not available.

General anesthesia is required during bronchoscopy to suppress coughing and laryngospasm, to allow examination of the airways without inducing trauma, and to protect the endoscope. Bronchoscopy can be performed using gas anesthesia if the animal is large enough for a 7–8 mm endotracheal tube. A special T adapter is used to pass the scope through the endotracheal tube while administering anesthetic gas and venting expired gases ( Figure 2.18). In small dogs and cats, jet ventilation is typically used to provide oxygenation through bulk flow, because placement of the scope through a small endotracheal tube would lead to airway obstruction and accumulation of CO 2. As an alternative, oxygen can be supplied to the patient using a red rubber catheter attached to the oxygen supply. The catheter should terminate in the distal trachea to avoid the possibility of wedging it into a bronchus and causing airway rupture.

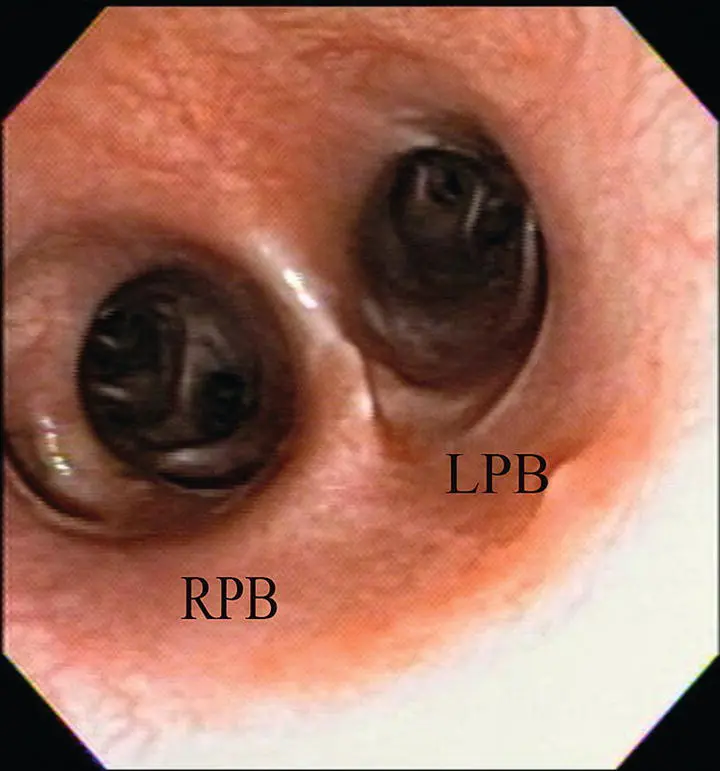

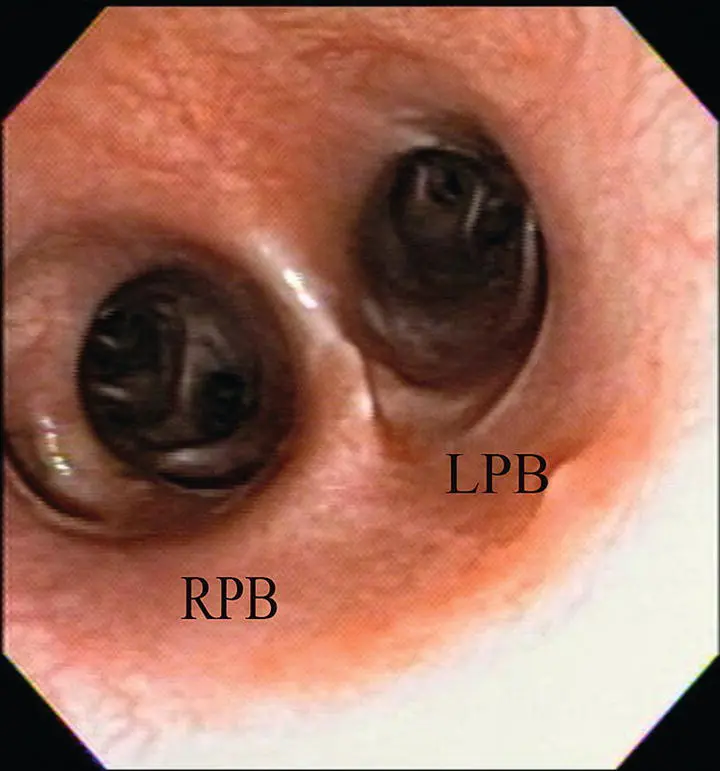

Virtually all animals undergoing bronchoscopy suffer respiratory embarrassment. Prior to bronchoscopy, patients are preoxygenated with a facemask, and an anesthetic protocol is chosen that avoids excessive cardiopulmonary depression. Animals are placed in sternal recumbency and two mouth gags are in place throughout the procedure to protect the bronchoscope. The normal trachea appears round to oval, with minimal laxity in the dorsal tracheal membrane ( Figure 2.19). At the carina, bifurcation in the left and right mainstem bronchi provides a reliable landmark for assessing location within the airways ( Figure 2.20). Normal airways appear round to oval in shape, demonstrate little change in shape or diameter throughout respiration, have minimal secretions, and are pale pink in color ( Figure 2.21). All accessible airways should be evaluated and abnormal regions with mucosal hyperemia or irregularity or areas with mucus accumulation should be identified as possible sites for BAL. If an obviously abnormal site is not visualized, the right middle lobe or caudal portion of the left cranial lobe is often a worthwhile site to lavage, because they are both ventrally oriented and tend to accumulate secretions.

Figure 2.18 A bronchoscopy adapter allows passage of a 5.0 mm endoscope through an endotracheal tube while oxygen and anesthetic gas are administered through the side port.

Figure 2.19 Endoscopic view of the normal canine trachea.

Figure 2.20 Endoscopic view of the carina illustrating the openings into the right principal bronchus (RPB) and left principal bronchus (LPB).

Читать дальше