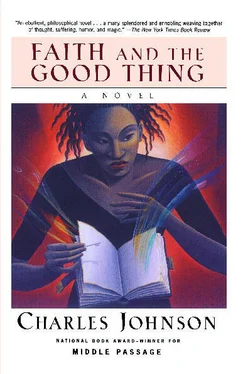

Charles Johnson

Faith and the Good Thing

For Art Washington,

friend and brother

Fides ergo est, quod non vides credere.

— St. Augustine

Allah delights in many kinds of Truth and Truth in many degrees, but even Allah doesn’t like the entire Truth.

— Arabian Saying

It is time to tell you of Faith and the Good Thing. People tell her tale in many ways — conjure men and old gimped grandmothers whisper it to make you smile — but always Faith Cross is a beauty, a brown-sugared soul sister seeking the Good Thing in the dark days when the Good Thing was lost or, if the bog-dwelling Swamp Woman did not lie, was hidden by the gods to torment mankind for sins long forgotten.

Listen.

The Devil was beating his wife on the day Faith’s mother, Lavidia, died her second death. The first, an hour-long beating of bedsheets pierced by grating breaths, had been the day before, but a country doctor, Leon Lynch, came to the farmhouse where they lived and massaged Lavidia’s heart. She returned from wherever it was she had been, both her legs pumping beneath the covers, her white eyes wide with terror. Lavidia raced like that the entire night, into the next day, and would have broken all long-distance records if she’d not been flat on her back. Finally she rested, counting her breaths. Faith, eighteen years old that day, stood at the window of her mother’s bedroom, staring at a red sun as flat and still against the sky as moonlight on pond water. Light at first, like the sprinkle of baptism, yet steadily building, the dissolution of the clouds drenched the twenty acres of land left to Lavidia by her husband. Todd Cross had died in an odd way, so odd no one had spoken of him in Hatten County, Georgia, for twelve years. And now Faith’s mother breathed her last.

Lifting the hem of her dress, Faith dried her eyes and turned from the window. She walked barefoot along the uneven wooden floorboards, circled an openmouthed stove in the center of the room, and sat beside her mother’s bed on an old fiddleback chair. Judging from the photographs on her dresser, Lavidia Cross, during the Great Depression, had been a handsome woman. She once had worn back her long brown hair, her skin sparkled from homemade lard, and her limbs were strong and sturdy. But at fifty-five, her figure was gray, both her arms spindly, and her swollen legs, drawn beneath the covers and quilts close to her breasts, were as soft as those of a toad. On the wall above her head swung a dull cross beside a calendar no one had changed for months. To Faith’s right were Lavidia’s wig stand, her lamps made from vinegar bottles, and a heavy maple-framed mirror, her mother’s favorite heirloom. But Lavidia herself was slipping slowly out of time. Cockroaches lost their balance on the damp wall and fell along her face. These Faith quickly removed. Only light from the parted drapery of the room’s single window lit the room. Water dripped from a ceiling sagging at its center. And the walls shuddered with each crash of thunder, the time between thunder rolls freighted with waiting. With mourning. Faith placed her fingers under the heavy covers to touch her mother’s hand. It was cold.

“Momma,” she said.

Lavidia’s discolored eyes closed, her mouth sprang open, a web of spittle spread between her lips. “Don’t ask me no questions,” she said. “. Lord give me four hun’red million breaths to take, and I’m already on the three hun’red ninety-second millionth — I can’t waste none on foolish questions.”

Faith began to cry. “I called for Reverend Brown. He’s outside. ”

Lavidia’s eyes opened as though to drink in a vision. She stared sightlessly at Faith, and the blankets rose again with the kicking of her legs. Lavidia said, “Girl, you get yourself a good thing”; then she gulped once, whispered, “Four hun’red million,” and died.

Behind her, Faith heard the bedroom door creak open. Through the doorway came the chubby preacher, Lucius Brown, and Oscar Lee Jackson, town mortician. Jackson, who wore a linty black suit and held his mottled hands folded in front of his paunch, stepped quietly inside the room and said, “Is she.?”

Faith shook her head and quietly withdrew her hands from the covers. “Momma’s resting.”

Brown and Jackson went right to work. Jackson covered the empty eyes and open mouth on Lavidia’s face with a bedsheet; Brown placed his arm around Faith’s shoulders to lead her into the kitchen, blew his flat nose, and said, “I know she’s gone to Glory. You believe that, Faith.”

Faith, lowering her head to her hands, wept. “She couldn’t be going to Glory the way she was running. Momma must have got where she was going the first time, turned around scared, and run all the way back.”

“And,” Brown said softly, “started runnin’ straight for Glory.”

From the table, they could see through the kitchen window that Jackson and his two assistants had straightened out Lavidia’s legs and were carrying her on a stretcher to the open door of a hearse idling just yards from the front porch. Brown’s eyes rolled toward the ceiling; he said something pious in a deep voice, reached across the table, and stroked Faith’s hand. “What will you do now, child?”

Do? Faith paused, squinting her eyes to clear her head. The kitchen had changed. You could locate nothing misplaced, nothing out of the ordinary, for as a housekeeper Lavidia was meticulous; but the kitchen’s former gloss of permanence was gone. Its smell was still that of the dry cotton fields just outside the open window above the sink, of browning bread Lavidia had baked just two nights before; yet Lavidia was gone. Though old, dissipated, sometimes evil, she had been the focus of the farmhouse since her husband’s death, its most crucial node, surely its mistress. Without her the kitchen, the house, the world beyond fell apart. Fruit cabinets on the wall still held sweet jellies preserved in the odd-shaped bottles Lavidia salvaged like a scavenger from house and yard and rummage sales; her stiff mops and silver pail still rested in the corner by brooms she’d assembled by hand. Then what had changed? Certainly not the things themselves. Studying Lavidia’s dresses heaped in a washtub by the door, her pipes in their dusty rack on the kitchen table, and dry lifeless wigs, Faith felt her answer emerge from the contours of these objects: none of them was for her; they belonged, related to no one. Even Lavidia, perhaps, had not made them her own, because — with her death — they seemed suddenly freed to be as they were. Empty things, cold, without quality, distant. Without order — it was evident — there could be no life, no sense to things, no way to awake in the stillness of morning and move from the day to and through the terror of eveningtime.

Her thoughts like wild animals fed upon themselves. Before her, out there, the wall stretched completely beyond all familiarity, possession, and warmth. She felt the urge to touch it, to reclaim it as the same wall against which Lavidia had measured her height across eighteen years. But if she touched it, might it not tumble away?

Faith looked down at her hand lying brown and crablike on the checkered tablecloth. Was it her hand? There was grave doubt, yes, of even this. She let it rest on Reverend Brown’s blunt fingers, thought, “Spread your fingers,” and was amazed at the result. The fingers spread, but between the command and the movement only a vague parallel held sway. Things had only a tenuous connection. The unreality of life without Lavidia melted even the gloss of permanence she felt enveloped her own life. No longer was she Faith, only child of Todd and Lavidia Cross, no longer was she what she believed herself to be; only a self-conscious pressure drifting about the empty, changing, charged-with-otherness kitchen, drifting through a cold space filled with shadows.

Читать дальше