Edges don’t have a thickness. This one’s a little tricky to get your head around. You never have to worry about how thick the edges in your model are because that’s not how SketchUp works. Depending on how you choose to display your model, your edges may look like they have different thicknesses, but your edges themselves don’t have a built-in thickness.

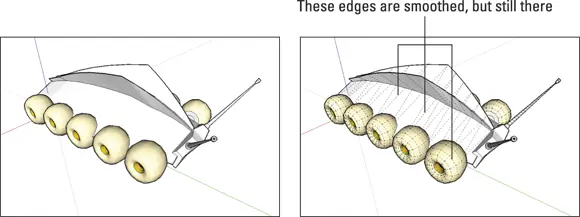

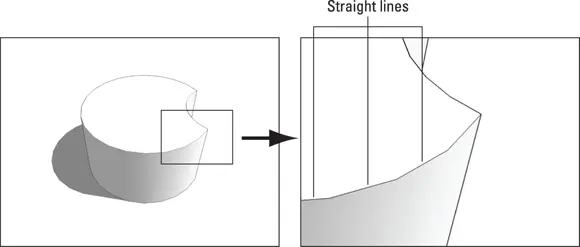

Just because you can’t see the edges doesn’t mean they’re not there. Edges can be hidden so that you can’t see them; doing so is a popular way to make certain forms. Take a look at Figure 3-3. On the left is a model that looks rounded. On the right, the hidden edges are visible as dashed lines. See how even surfaces that look smoothly curved are made of straight edges?

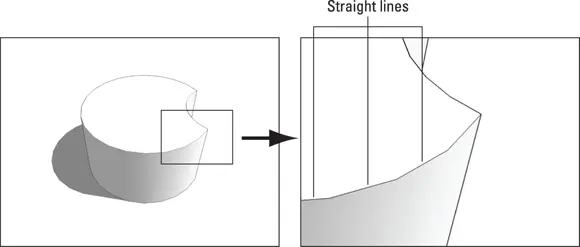

FIGURE 3-2:Even curved lines are made up of straight edges.

FIGURE 3-3:Even organic shapes and curvy forms are made up of straight edges.

Facing the facts about faces

Faces are surfaces. If you think of SketchUp models as being made of toothpicks and paper (which they kind of are), faces are basically the paper. Here’s what you need to know about faces:

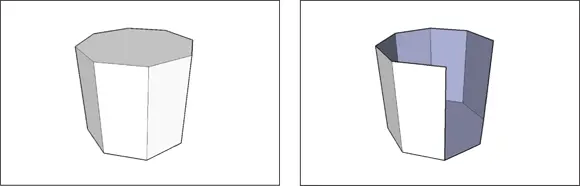

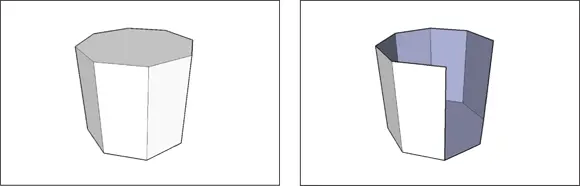

You can’t have faces without edges. To have a face, you need to have at least three coplanar (on the same plane) edges that are connected. In other words, a face is defined by the edges that surround it, and those edges all have to be on the same flat plane. Because you need at least three straight lines to make a closed shape, faces must have at least three sides. There’s no limit to the number of sides a SketchUp face can have, though. Figure 3-4 shows how faces can disappear when you erase an edge that defines one or more faces. We started with the model on the left and deleted the edge that completed both the top face and one of the side faces. The result, shown on the right, is that both of those faces disappeared.

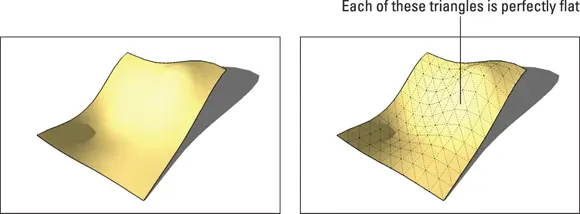

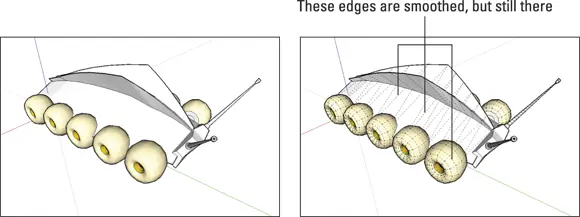

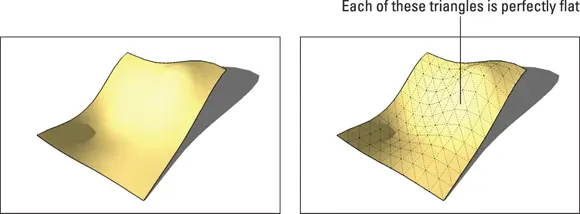

Faces are always flat. In SketchUp, even surfaces that look curved are made of multiple, flat faces. In the model shown in Figure 3-5, what look like organically shaped surfaces (on the left) are really just lots of smaller faces (on the right). Think of the many small mirrors that make up the surface of a nightclub disco ball. To make a bunch of flat faces look like one big, curvy surface, the edges between them are smoothed. You find out about smoothing edges in Chapter 6.

Just like edges, faces don’t have any thickness. If faces are a lot like pieces of paper, they’re infinitely thin pieces of paper; they don’t have any thickness. To make a thick surface (say, a 6-inch-thick wall), you need to use two faces side by side. In SketchUp, even a solid concrete wall will be hollow.

FIGURE 3-4:You need at least three coplanar edges to make a face.

FIGURE 3-5:All faces are flat, even the ones that make up larger, curvy surfaces.

Understanding the relationship between edges and faces

Now you know that models are made from edges and faces, you’re most of the way to understanding how SketchUp works. Here’s some information that should fill in the gaps:

Every time SketchUp can make a face, it will. There’s no such thing as a “Face tool” in this software; SketchUp just automatically makes a face every time you finish drawing a closed shape out of three or more coplanar edges. Figure 3-6 shows this in action: As soon as a line connects the last edge to the first one, SketchUp creates a face. FIGURE 3-6:SketchUp automatically makes a face whenever you create a closed loop of coplanar edges.

You can’t stop SketchUp from creating faces, but you can erase them if you want. If SketchUp creates a face you don’t want, just right-click the face and either choose Erase from the shortcut menu or tap the Delete key on your keyboard. That face is deleted, but the edges that defined it remain, as illustrated in Figure 3-7.

Retracing an edge re-creates a missing face. If you already have a closed loop of coplanar edges but no face (because you erased it, perhaps), you can redraw one of the edges to make a new face. Just use the Line tool to trace over one of the edge segments, and a face reappears, as shown in Figure 3-8.

Drawing an edge all the way across a face splits the face in two. When you use the Line tool to draw an edge from one side of a face to another, you cut that face in two. The same thing happens when you draw a closed loop of edges, such as a rectangle on a face: You end up with two faces, one “inside” the other. In Figure 3-9, we split a face in two with the Line tool and then extruded one face a little bit with the Push/Pull tool. FIGURE 3-7:You can delete a face without deleting the edges that define it. FIGURE 3-8:Just retrace any edge on a closed loop to tell SketchUp to create a new face. FIGURE 3-9:Splitting a face with an edge and then extruding one of the new faces.

Drawing an edge that crosses another edge splits both edges where they touch. In this way, you can split simple edges you draw with the Line tool, as well as edges created when you draw shapes like rectangles and circles. Most of the time, this autoslicing is desirable, but if it’s not, you can always use groups and components to separate your geometry. Flip to the first part of Chapter 5for more information.

Drawing in 3D on a 2D Screen

For computer programmers, drawing 3D objects on your screen is a difficult problem. You wouldn’t think it’d be such a big deal; after all, people have been drawing in perspective for a very long time. If Fillipo Brunelleschi could figure it out 500 years ago, why should your computer have problems?

The thing is, human perception of depth on paper is a trick of the eye. It isn’t really an optical illusion; it just looks like one. And of course, your computer doesn’t have eyes that enable it to interpret depth without thinking about it. You need to give your computer explicit instructions. In SketchUp, this means using drawing axes and inferences, as we explain in the sections that follow.

DON’T WORRY ABOUT DRAWING IN PERSPECTIVE

DON’T WORRY ABOUT DRAWING IN PERSPECTIVE

Contrary to popular belief, modeling in SketchUp doesn’t involve drawing in perspective and letting the software figure out what you mean. This turns out to be a very good thing, for two reasons:

Computers aren’t very good at figuring out what you’re trying to do. This has probably happened to you: You’re working away at your computer, and the software you’re using tries to “help” by guessing what you’re doing. Sometimes it works, but most of the time it doesn’t. The word processing software we all use is a good example. Eventually, the computer’s bad guesswork gets really annoying. Even if SketchUp could interpret your perspective drawings, you’d probably spend more time correcting its mistakes than actually building something.

Читать дальше

DON’T WORRY ABOUT DRAWING IN PERSPECTIVE

DON’T WORRY ABOUT DRAWING IN PERSPECTIVE