In the nineteenth century, egg collecting for human consumption throughout Britain and Ireland was extensive. In some areas it was organised by the landowners, but elsewhere it appears to have been uncontrolled. Well-established markets existed in London, and eggs collected in bulk in Norfolk and Hampshire were sent there for sale. That the Black-headed Gull was widely distributed as a breeding bird in southern England is evident from records of the large numbers of their eggs being collected and sold in the London markets. For example, in 1800 some 8,000–9,000 eggs were collected at Scoulton Mere in Norfolk, while in 1864 and later, 2,000 eggs a year were collected. From 1858, 700 eggs were taken each year at Hoveton in Norfolk, and in 1864 alone, 2,000 eggs were collected. According to The Spectator (17 April 1897), in 1834 at Stanford in Norfolk, a ‘tumbrel-load’ of eggs was collected in a day and sold for 3d a dozen.

It is probable that landowners enforced a degree of protection to the gull colonies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries owing to the value of the egg trade. In some cases, collecting was limited to taking eggs only from nests that held one or, occasionally, two eggs, to ensure that those collected had not been incubated, and at some but not all sites, collecting ceased on 15 June. As a result, clutches of three eggs were often left untouched, while cessation of collecting in June permitted some gulls to re-lay and breed successfully from late, repeat clutches.

An account of annual egg collecting in Ayrshire, Scotland, in the first 40 years of the twentieth century is given by Ruth Tittensor in a 2012 edition of Ayrshire Notes. The eggs were collected for local bakeries and domestic use, and even for egg fights between youths. Interestingly, the article includes a personal account of egg collecting by a person who later became a senior member of the Nature Conservancy! Elsewhere, the sale of eggs also continued into the twentieth century. In the 1930s, for example, more than 200,000 gull eggs were sold annually at Leadenhall Market in London. Egg collecting increased extensively during the two world wars, with large numbers collected to supplement rationing. An archived Pathé News ciné film shows several Land Girls based at Muncaster Estate during the Second World War collecting baskets of eggs at the large Ravenglass colony and boxing them up in crates ready for dispatch to London. Hugh Cott describes eggs being on sale in Cambridge in 1951 at 9d each. A London market for Black-headed Gull eggs existed for the whole of the twentieth century, with some being sold as ‘plovers’ eggs’.

Today, despite current bird protection Acts, systematic collecting of Black-headed Gulls’ eggs is still permitted in England by licence holders, although there is little general knowledge of the numbers of licences and eggs collected. The licences are issued annually by Natural England for collecting eggs for food consumption. As a result of a request for information, Natural England responded in 2016 by stating that ‘Licences are only issued where evidence of hereditary/ancestral/traditional family rights to collect eggs can be given’. The public body also stated that it seeks ‘to ensure that collection of eggs is sustainable in relation to numbers collected and colony size’. However, I still await a response as to how this is achieved and where the records are deposited, since they do not appear in the Seabird Colony Register or local county bird reports. An accurate census of a colony where many eggs are collected is often difficult to carry out because of the greater spread of laying and repeat clutches.

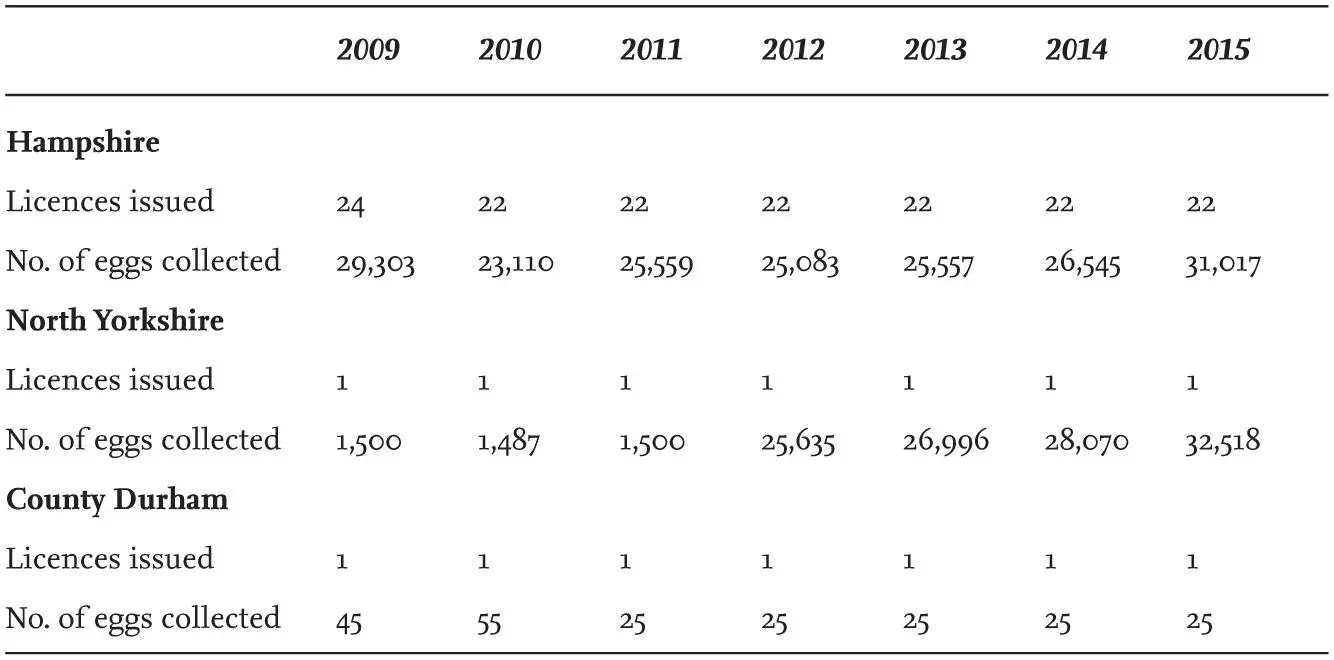

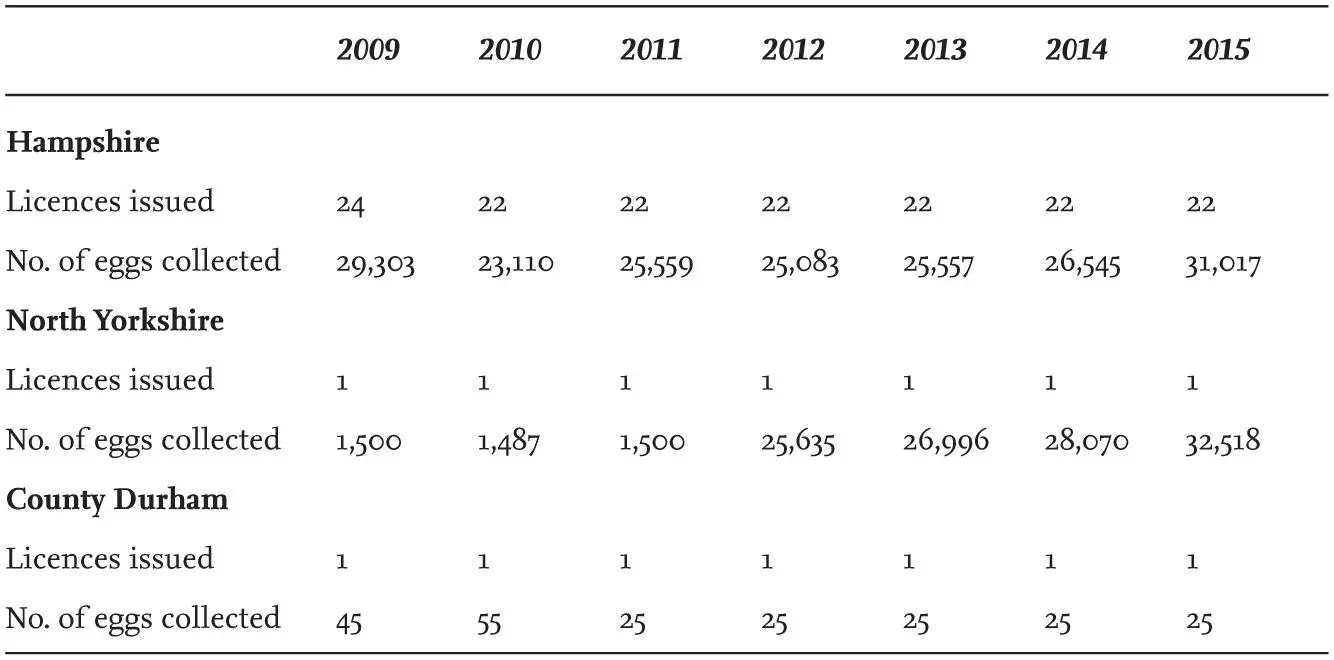

A freedom of information request granted by Natural England in 2016 revealed that it had issued licences recently for egg collection at six sites in England: the North Solent nature reserve in Hampshire; Lymington, Pylewell and Keyhaven marshes, also in Hampshire; Barden Moor in North Yorkshire; and the Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve in County Durham. Currently, up to 40,000 eggs are collected annually and sent to London. These details are not publicised and I found no information in the published literature. A further freedom of information request to Natural England revealed that in 2015 it issued 24 licences to collect Black-headed Gull eggs in England (22 in Hampshire, one in Yorkshire and one in County Durham). Table 10shows that the numbers of eggs collected in Hampshire remained at about the same level over the period 2009–15. Those taken in North Yorkshire increased 17-fold between 2011 and 2012, and since then the numbers collected have continued to increase, with more than 32,000 eggs taken in 2015.

No mention of these annual egg collections appear in recent county ornithological reports, while Natural England made the surprising statement that information prior to 2008 ‘has not been retained’. This public body should not destroy historical information on colony sizes and the numbers of eggs collected, and such data should be archived. Natural England also refused to identify the colonies from which eggs were collected, or to whom licences were issued, thereby preventing further research on these activities. How this quango carries out the annual monitoring of the colonies – as it claims to do – remains unknown, and why this information is not deposited in the national Seabird Colony Register, which it supports, requires investigation. It is likely that eggs laid by Mediterranean Gulls (Larus melanocephalus) are being inadvertently taken at some of the colonies for which licences are issued.

TABLE 10. The number of egg-collecting licences issued and Black-headed Gull eggs collected in Hampshire, North Yorkshire and County Durham in 2009–15, as reported by Natural England. The public body stated that data for earlier years have not been retained.

Natural England has indicated that the licences place restrictions on the dates of collecting, these normally covering the period 1 April to 15 May each year. They also restrict the length of time collectors can spend in the colonies on each visit. Natural England revealed that the County Durham licences authorise collection of eggs from three large colonies of gulls, which therefore must be in Upper Teesdale, but the quango is not willing to disclose which colonies are involved.

Black-headed Gull eggs collected in England are currently sold by up-market London stores and find their way onto the menus of several prestigious restaurants. The eggs are normally served hard boiled or lightly boiled and seasoned with celery salt, and a serving containing three eggs may cost anything from £7.50 to £22. One restaurant in 2015 was offering omelettes made from three gulls’ eggs filled with lobster meat.

WINTER ABUNDANCE

Few British-reared Black-headed Gulls leave the region in winter, with most making only local movements. Of those that do migrate, a higher proportion move to Iberia from south-east England than those reared in north-east Britain ( Fig. 25). In contrast, large numbers of Black-headed Gulls move from the Continent to winter in Britain and Ireland.

FIG 25. Movements of Black-headed Gulls ringed as nestlings in south-east England and recovered outside the breeding season, based on 976 recoveries. Right: Similar mapping, but based on 447 recoveries of Black-headed Gulls ringed in north-east Britain. Note that fewer birds moved to Iberia from the north-east and that birds from the two regions have different winter distributions in Ireland. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

Читать дальше