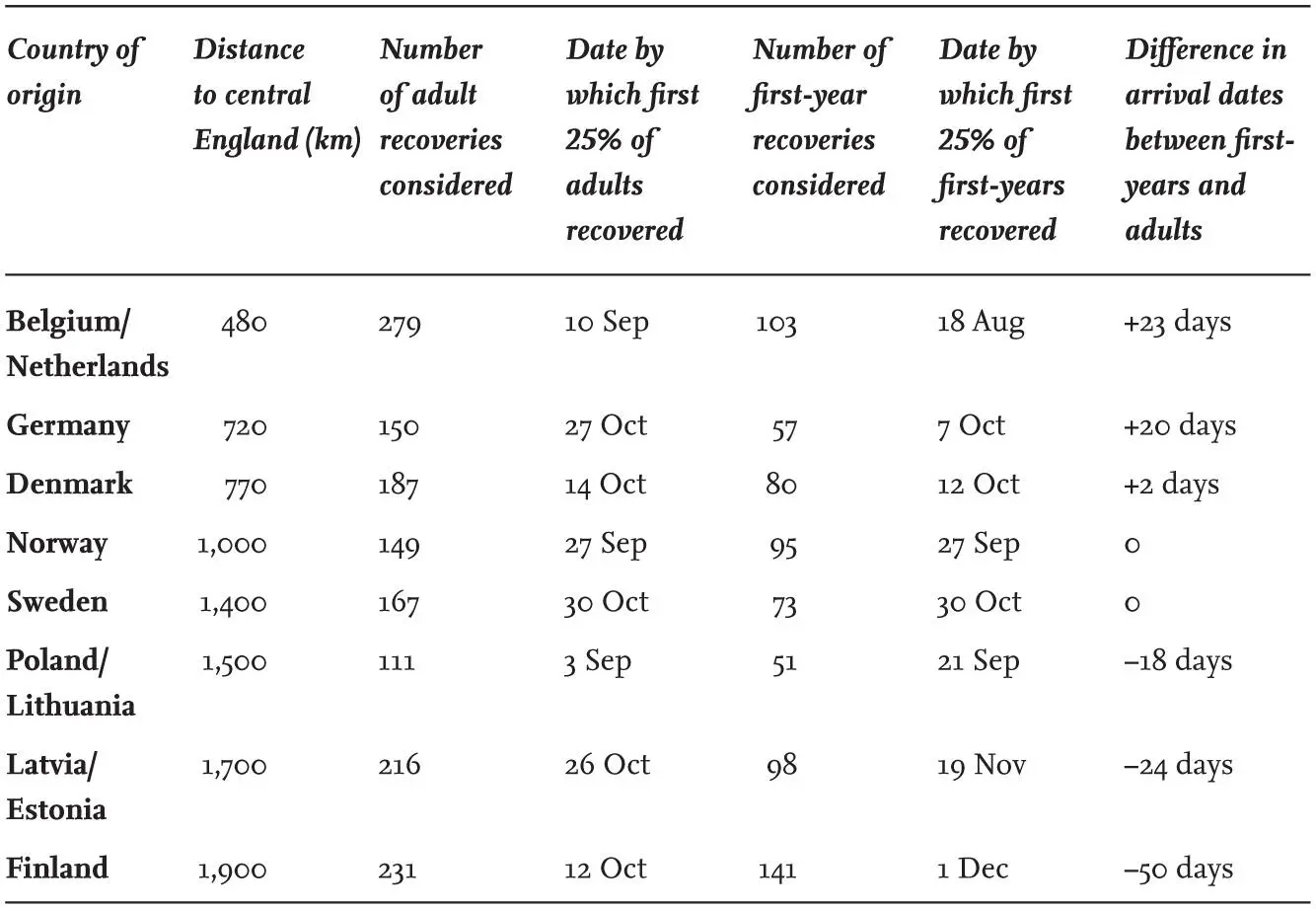

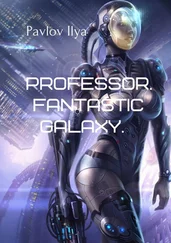

TABLE 11. Date by which the first 25 per cent of adult and first-year Black-headed Gulls ringed abroad have been recovered in Britain in each 12-month period, starting 1 July. Based on MacKinnon and Coulson (1986).

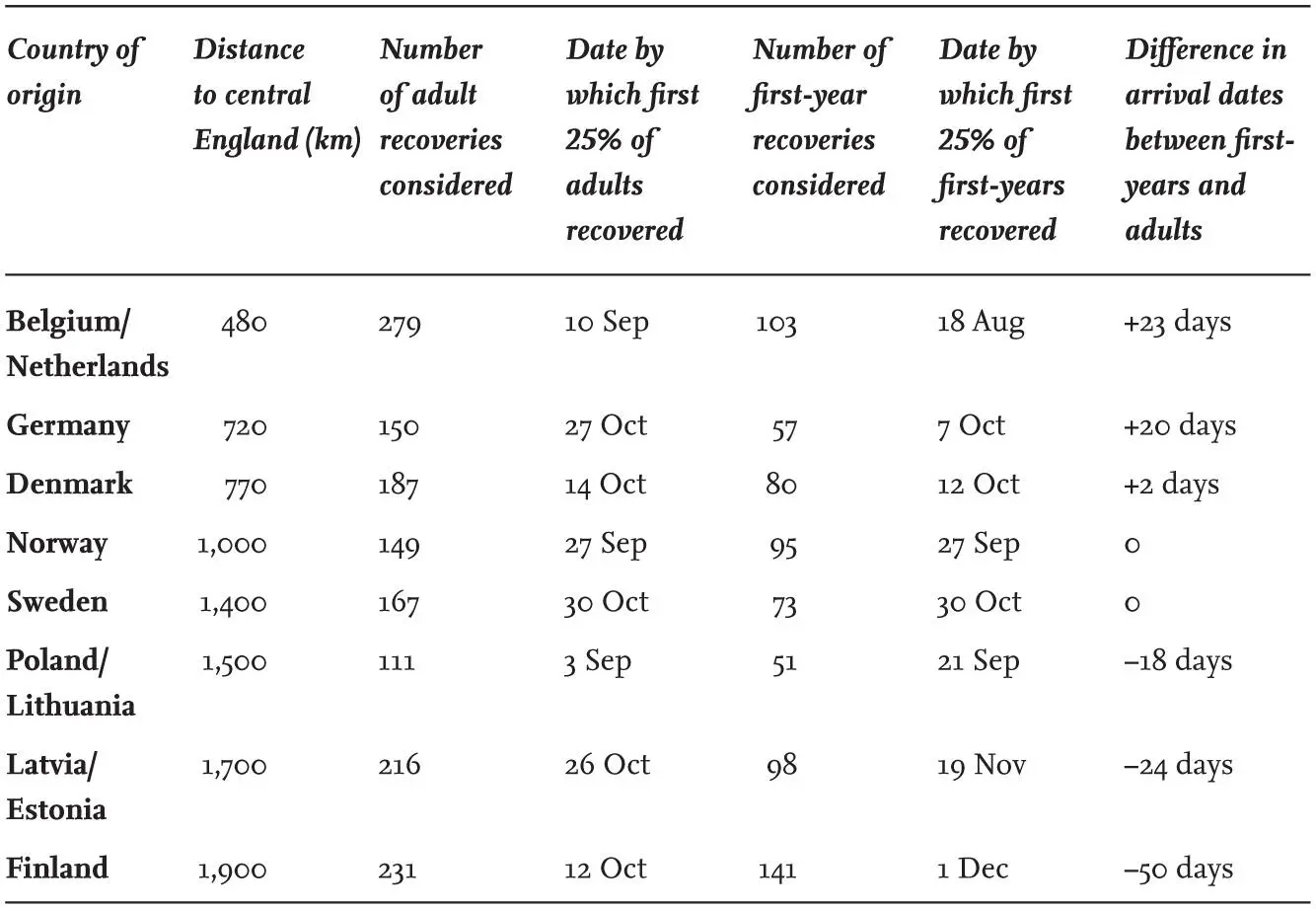

FIG 30. Difference in the dates of the first 25 per cent of recoveries in Britain of first-year and adult Black-head Gulls of Continental origin (data from Table 8) in each 12 months from 1 July, plotted against the distance from country of origin to central England. Note that the first-year birds from countries close to England arrived earlier than the adults, but that the converse was true for those travelling further.

Faithfulness to wintering areas

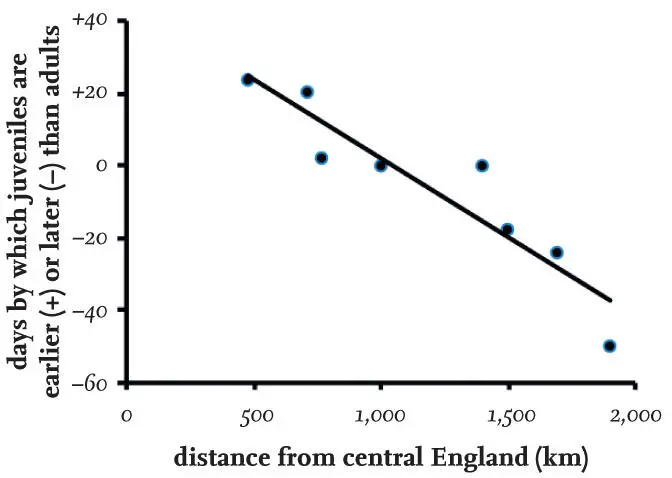

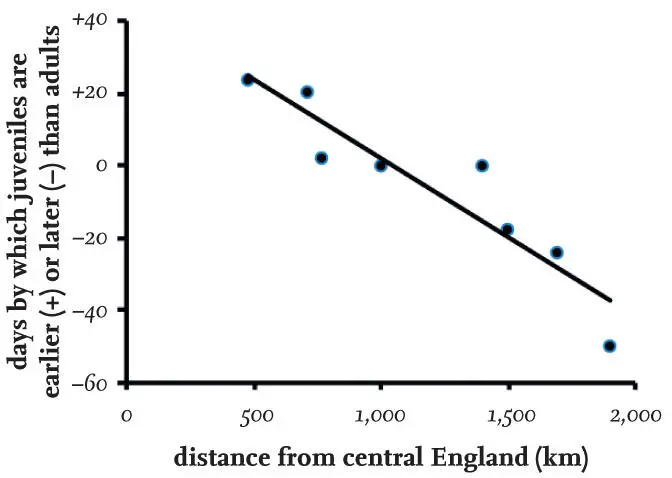

There is extensive and convincing evidence that some adult Black-headed Gulls from the Continent return to the same immediate wintering area year after year. The best example is a gull ringed in Poland, whose ring numbers were recorded in the same central London park over eight consecutive winters. However, such faithfulness to wintering areas is not absolute, as there are many instances of birds from the Continent wintering in Britain one year and then remaining in mainland Europe (usually in the Netherlands or Denmark) in the following winter ( Fig. 31). It has been suggested, but not yet proven, that relatively mild conditions in western Europe in some recent winters have resulted in fewer Black-headed Gulls migrating here; this effect has also been reported for several species of waders and other waterbirds.

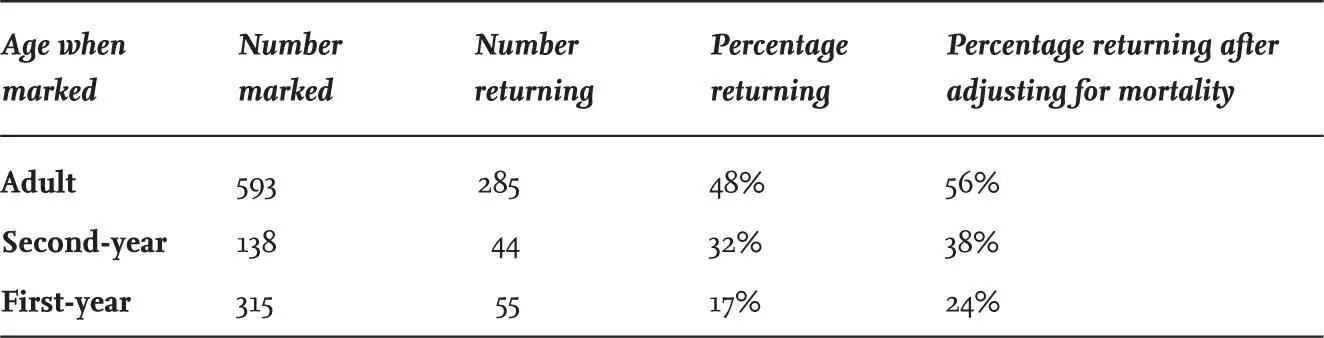

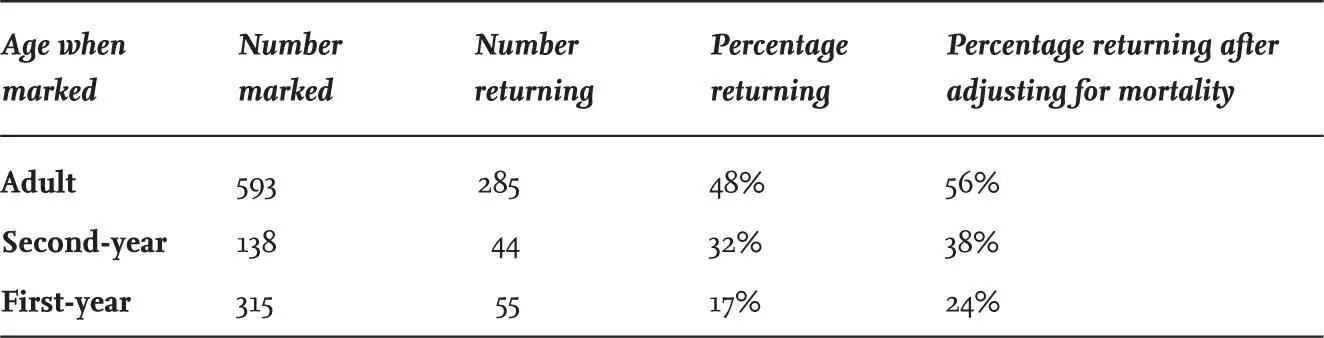

Evidence of the extent to which Black-headed Gulls use the same wintering area in successive years comes from individuals wing-tagged in north-east England, as these had a high probability of being seen if they returned in the following winter. Most tagged birds were breeding on the Continent, and so the annual return would involve many individuals migrating considerable distances. In the winter after tagging, those that returned were seen on an average of five different days, so it is unlikely that many others were missed. The study detected that 48 per cent of adults and 32 per cent of second-year birds, but only 17 per cent of first-year birds, returned to the same area in successive winters ( Table 12). Allowing for mortality in the intervening year (estimated at about 15 per cent for adults and 30 per cent for first-year birds), 56 per cent of the surviving adults returned to the same wintering locality, with 38 per cent of those in their second winter when marked returning for a second time, but only 24 per cent of those marked in their first year.

FIG 31. Black-headed Gulls ringed in winter in Britain and recovered more than 20 km away in a subsequent winter. Many individuals returned to Britain, but note the appreciable number that failed to do so in a subsequent winter and were recovered on the Continent. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

TABLE 12. The proportions of marked Black-headed Gulls that returned to the same wintering area the following year.

A total of 38 marked individuals that did not return to the study areas were seen by other observers elsewhere in the winter following marking. These were reported mainly on the east coast of Britain, south of the study areas. Two extreme cases were recorded; one bird 450 km away on the south coast of England, and the other 300 km north at Aberdeen in Scotland. In addition, one remained in Denmark. It is evident from this that only a proportion of individuals of all age classes return to the same wintering area, but that faithfulness is stronger (although not complete) in adults. The reason why some birds return while others fail to do so remains unknown, but is not primarily related to their sex.

Return of birds to the Continent

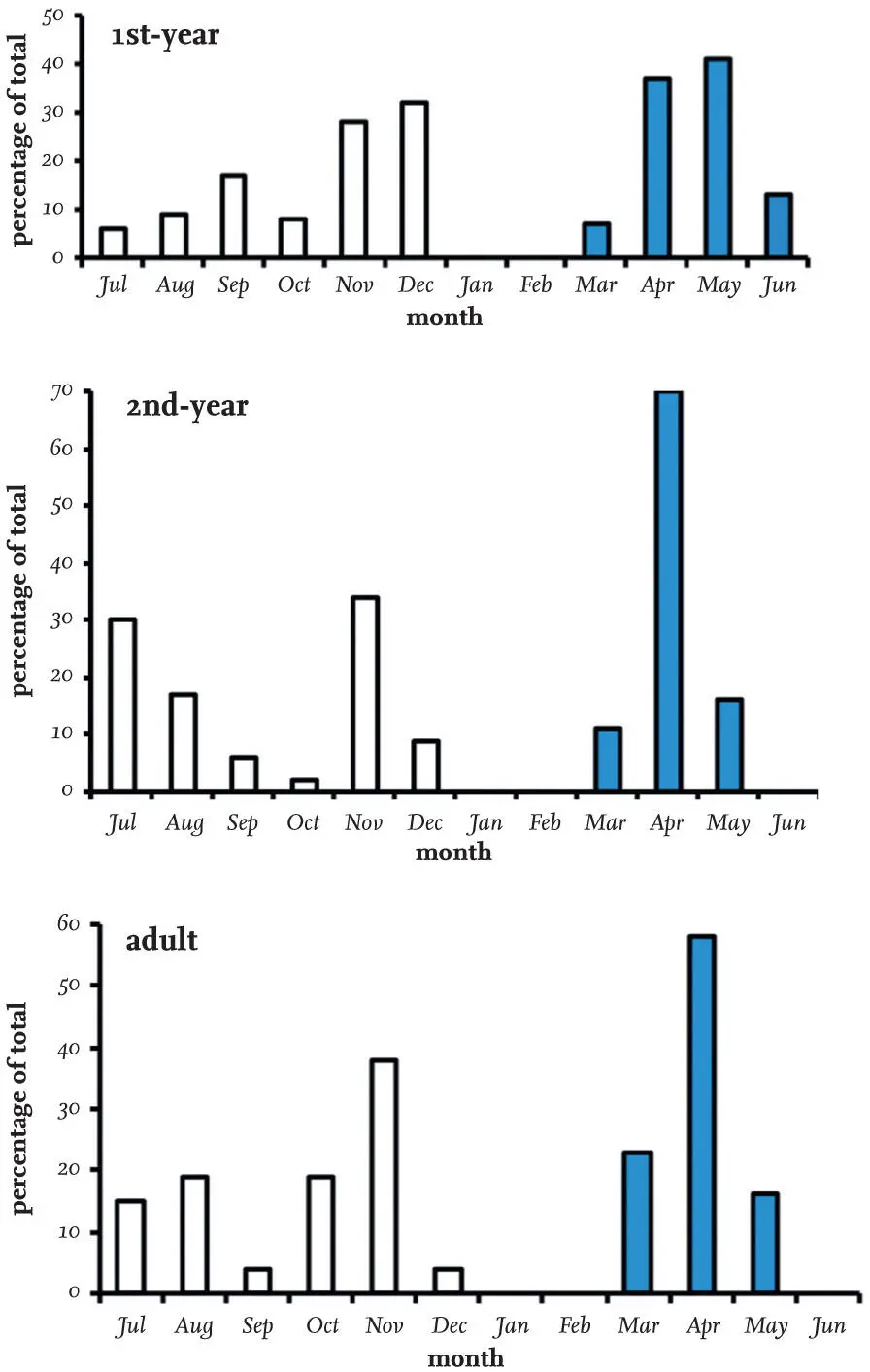

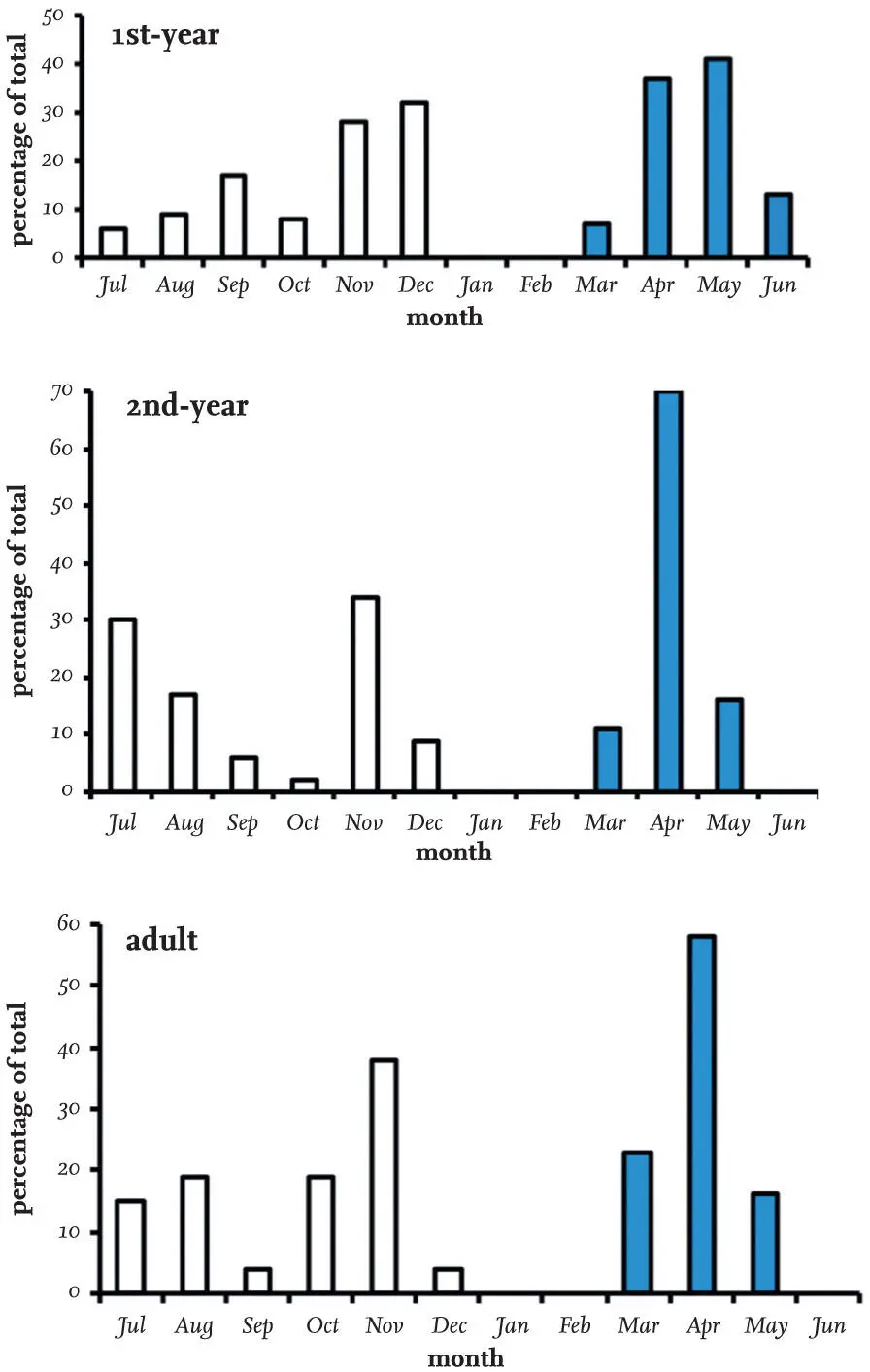

The return migration from Britain to the Continent is much more synchronised than the arrival and begins in late March, with most adults migrating in April ( Fig. 32). First-year birds tend to depart later than adults and some do not leave until May, while others (perhaps 10 per cent of immature birds wintering here) remain throughout the summer. These birds join the feeding adults associated with colonies in Britain (since they leave their wintering feeding areas) and presumably do not return to the Continent until they have overwintered here for a second time.

FIG 32. The month of arrival of Black-headed Gulls entering Britain from the Continent in autumn (white bars) and leaving in spring (blue bars), based on monthly change in numbers of ringing recoveries of foreign birds in Britain. Note that for all age classes, the spring departure is much more synchronised than the autumn arrival dates.

By the end of July, numbers of second-years have arrived in Britain and joined the few that spent the summer here. These birds are not constrained by breeding and moult about four weeks earlier than adults, so this might explain their early crossing of the North Sea. More arrive in late October and early November, and many late arrivals originate from further away, east of the Baltic.

Distribution of Continental wintering birds

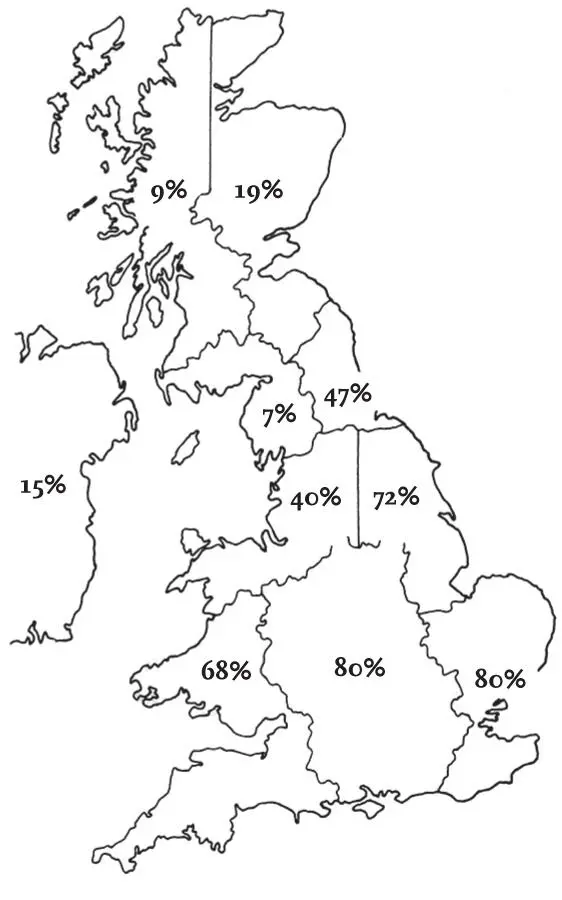

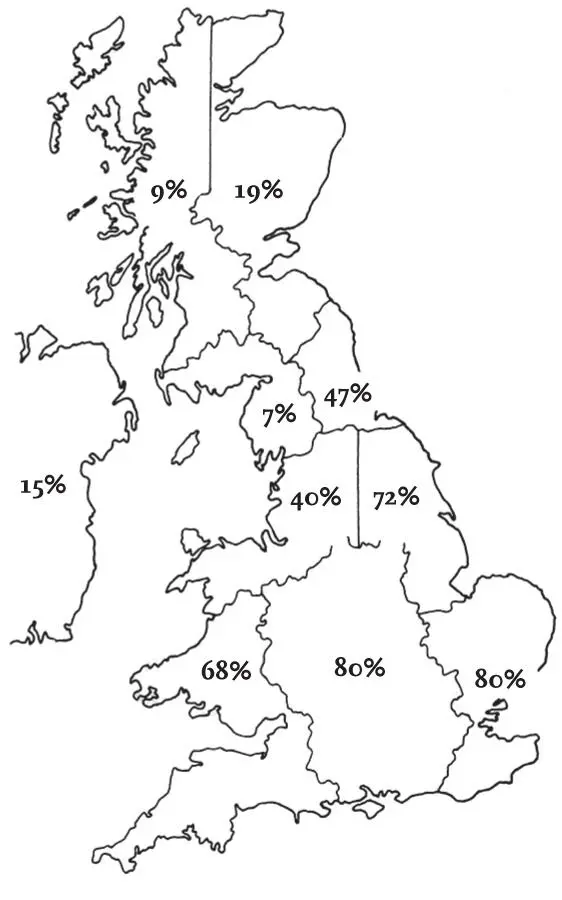

The Continental Black-headed Gulls that winter in Britain do not disperse randomly across the country, and are much more abundant in eastern and southern regions. The proportions of young gulls ringed in Britain or on the Continent and recovered from December to February in each of 10 regions of Britain and Ireland (4,267 recoveries in total) were used to produce an index of the proportions of geographical distribution in each area ( Fig. 33). The percentages of Continental birds in these different regions ranged from 7 per cent to 80 per cent, based on at least 115 recoveries in each region and, in most cases, many more. The wide range of percentages obtained suggests that they are a close approximation to the actual proportions of birds of Continental origin. Ireland, Scotland and Cumbria had low proportions of Continental gulls, while the highest proportions occurred in south Wales, southern England, and eastern England from Yorkshire southwards. Overall, about 71 per cent of the wintering gulls in Britain and Ireland originated from the Continent – a high value, but consistent with the much higher overall numbers of Black-headed Gulls reported here compared with estimates in the breeding season.

FIG 33. Estimates of the percentage of Continental Black-headed Gulls present in 10 regions of Britain and Ireland in winter based on numbers of recoveries of British and Continental ringed birds in each region between early December and the end of February.

Sex ratio of wintering birds

While the sex ratio of Herring Gulls and Great Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus) captured in Britain during the winter approaches equality, that of wintering Black-headed Gulls shows a marked skew, with many more males being present. The data in Table 13show that birds identified at breeding sites in northern England in May and June contained a minor excess of 108 males per 100 females. However, the sex ratio of wintering birds captured in England changed considerably, with a threefold excess of males in October and November, followed by the reversion of proportions to near equality between December to February. In the winter samples, most individuals were visitors from the Continent, and the skewed sex ratio in October and November suggests that either migrating males were arriving earlier than the females by an average of a month or more, or that males and females were feeding at different types of sites not sampled in those months, but were feeding at the same sites later in the winter. A total of 20 males and 11 females wing-tagged in the autumn were subsequently reported to have returned to the Continent, which gives some support for the suggestion that the bimodal pattern of the arrival time of Continental gulls ( Fig. 32) represents males migrating earlier than females.

Читать дальше