Ythan Estuary (Sands of Forvie) colony

Black-headed Gulls have nested at the Sands of Forvie at the mouth of the river Ythan, near Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, for many years. In the late 1980s, about 500 pairs nested there annually, along with Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Common Terns (Sterna hirundo) and Eiders (Somateria mollissima). Fox predation became intense in about 1990, when breeding Sandwich Terns and Black-headed Gulls abandoned the area and the number of young Eiders declined. In 1994, steps were taken to reduce and then exclude Foxes from the breeding areas, and in 1998 the first Black-headed Gulls returned to breed. Numbers increased rapidly in the following years and reached more than 1,500 pairs in 2002. This level was not maintained, but numbers exceeded 500 pairs each year up to 2012, when the colony size increased annually until 1,921 pairs were recorded 2016 ( Fig. 22).

Foulney and other colonies

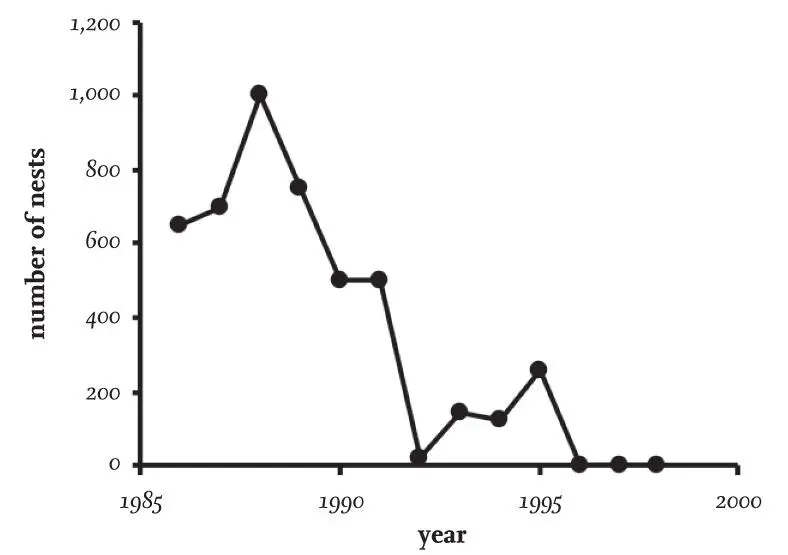

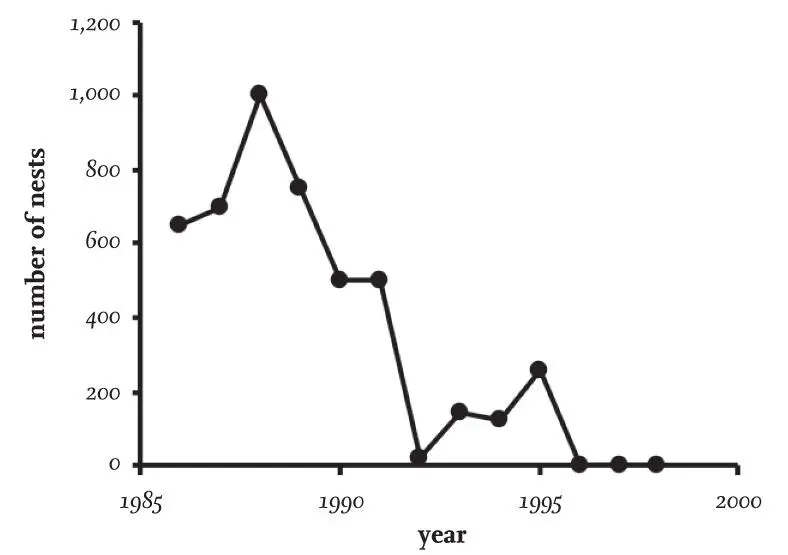

The colony at Foulney in north-west England ( Fig. 23) showed a pattern of decline spread over a few years in the late 1980s and early 1990s, before breeding there ceased altogether sometime in or before 1996. As elsewhere, predation of eggs and nestlings was considered the main cause.

FIG 23. The decline and subsequent total desertion of the Black-headed Gull colony at Foulney, a coastal site in Cumbria. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

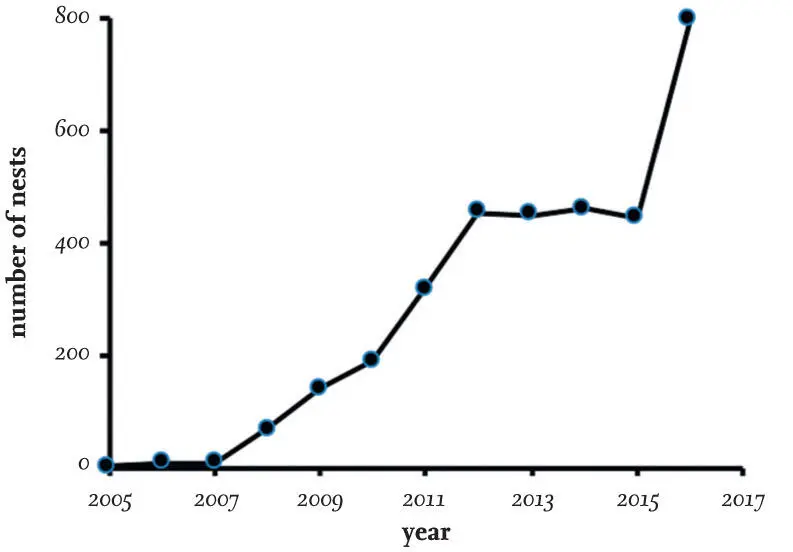

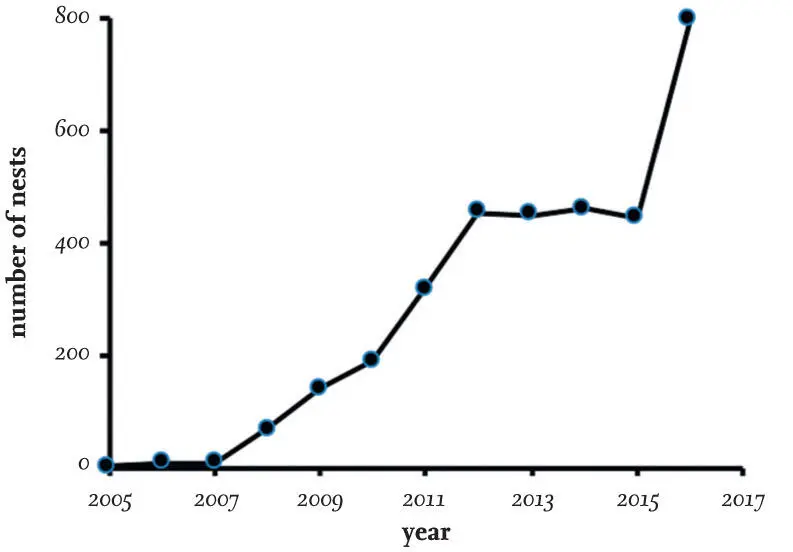

FIG 24. The rapid build-up of a Black-headed Gull colony at the RSPB reserve at Saltholme, near Stockton-on-Tees, between 2005 and 2017. Data mainly from the Seabird Colony Register.

There are many other examples of Black-headed Gull colonies that showed appreciably smaller numbers each year before breeding stopped entirely. The national census in 2000 listed 12 large colonies that had disappeared since 1985, plus a further five that had lost more than 89 per cent of the maximum numbers of breeding pairs over recent years. In contrast, nine colonies showed major increases within a short time period, including the colony at Langstone Harbour in Hampshire, which in the 15 years between 1985 and 2000 increased more than 60-fold. Many new colonies had become established and subsequently grew rapidly, such as those at Hamford Water in Essex, Coquet Island in Northumberland, Larne Lough in Northern Ireland, Loch Leven in Scotland, the Ribble Estuary in Lancashire and Saltholme ( Fig. 24), a nature reserve near Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham, that has been managed by the RSPB since 2007.

Reasons for colony declines

Egg collecting, particularly if stopped early in the season, has carried on year after year at several Black-headed Gull colonies without resulting in abandonment. And at Ravenglass, Neil Anderson’s investigations (see above) ruled out a possible link between the decline there and contamination associated with the nearby Sellafield nuclear fuel reprocessing and decommissioning plant. In many areas – particularly the fenland of eastern England – colonies have been lost due to drainage and expanding agriculture, which have removed otherwise suitable nesting sites. However, it seems that the main cause of decline and disappearance of Black-headed Gull colonies is predation of eggs, young and sometimes adults. The presence and increase in numbers of mammalian predators, particularly Foxes and American Mink, have been associated with the decline of the colonies at Sunbiggin Tarn, Ravenglass and the Sands of Forvie. During his studies at Ravenglass, Hans Kruuk found that four Foxes killed 230 Black-headed Gulls in one night, and a total of 1,449 adult gulls were killed by Foxes in two consecutive breeding seasons. Studies made at the colony by Ian Patterson during the period of appreciable mammalian predation activity found that scattered and outlying pairs of gulls were entirely unsuccessful, while those in the central core areas, although having a very low success rate, did succeed in rearing a few young (Patterson, 1965).

Once colonies have started to decline, the impact and pressure from the same numbers of Foxes or American Mink produce a vicious spiral that has an increasing impact on the remaining birds. Another predator at Ravenglass was the Hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus), which had developed the habit of consuming the flesh of live gull chicks that had not reached fledging age. Several of the colonies referred to in the past as sites where eggs were collected have now ceased to exist, and some authors have attributed these to uncontrolled egg collecting extending throughout the entire breeding season. It is ironic, therefore, that it was only after egg collecting had stopped at Ravenglass that the colony declined and then disappeared, presumably owing to the lack of efficient predator control.

When a colony disappears in a matter of a few years, it is unlikely that the adults have died, but rather that they have moved to other sites and colonies. The decline at Sunbiggin Tarn following predation resulted in some adults moving to Killington Reservoir alongside the M6 motorway in Lancashire, a move confirmed by a few ringing recoveries of adults previously marked at Sunbiggin Tarn. However, this colony contains nowhere near the numbers of birds recorded breeding at Sunbiggin Tarn, which implies that many adults from Sunbiggin probably moved considerable distances and to several different sites, as no other single large colony was established within 80 km of it at the time of its decline. This is also true of many small, ephemeral colonies on upland moorland in northern England and Scotland. A consequence of this is that mobile groups of Black-headed Gulls are often overlooked, and new colonies can grow rapidly through immigration in only a few years – as has happened at Saltholme ( Fig. 24).

Exploitation of eggs and young

In the past, both the eggs and young of Black-headed Gulls were extensively exploited in Britain by humans. Michael Shrubb gives a detailed account of this in his 2013 book, Feasting, Fowling and Feathers, from which I have extracted some of the information given below.

Through the combination of Black-headed Gull numbers, their extensive inland breeding often close to human populations, and the relatively easy access to many nests compared to those of gull species that nest on coastal islands and sea cliffs, the eggs of this species have been exploited more extensively than those of other gulls in Britain and Ireland for the past 500 years and probably longer. In some places in the sixteenth century, nearly fledged young were collected by driving them into nets, and they were then housed and fed until required for human consumption. Some were purchased by the wealthy for 4–5d each, (equivalent to about £7 at today’s prices) or given as gifts, just as we now give flowers. Oxford college records at the time also list Black-headed Gull eggs being bought for a fraction of a penny each.

In the seventeenth century, one landowner is said to have made a profit of £60 in one year (equivalent to about £7,000 today) by collecting and selling gulls’ eggs. Exploitation of young birds probably decreased over time, but they continued to be sent to London markets nonetheless, and egg collecting became more frequent and extensive. Exploitation continued into the eighteenth century, and there are more records at this time of eggs being collected throughout England and Scotland. There are also records of gull colonies disappearing, the causes of which were attributed at the time to excessive egg collecting.

Читать дальше