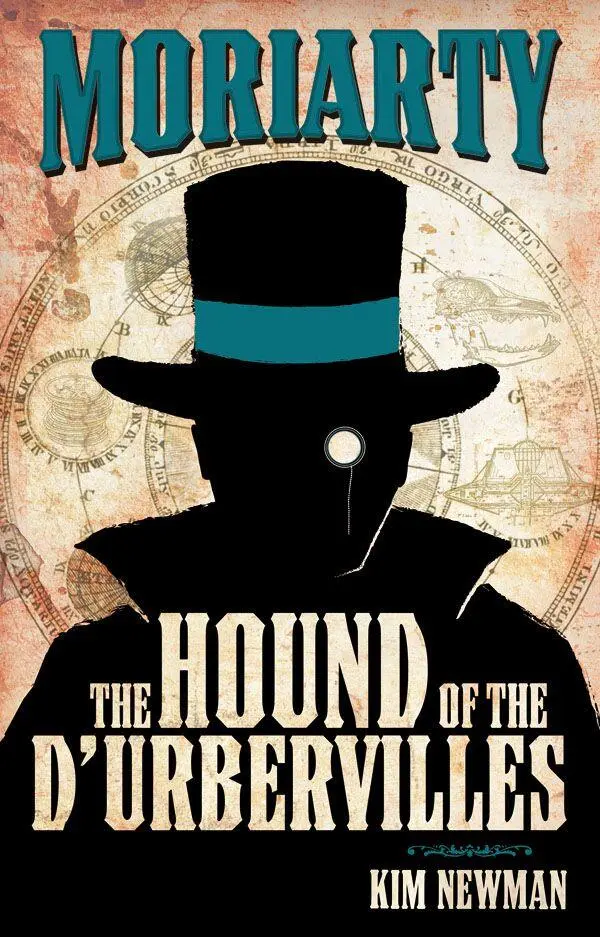

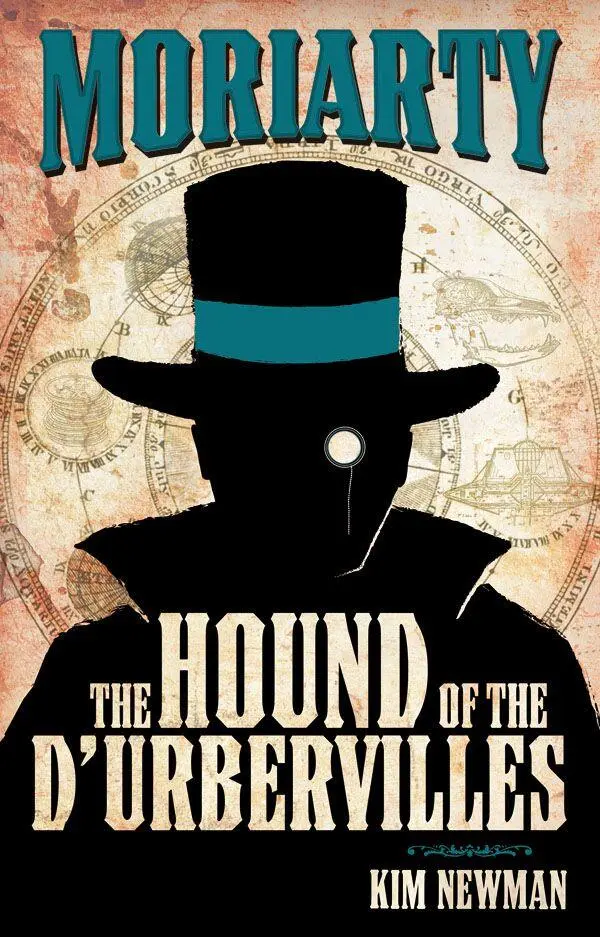

Kim Newman

Professor Moriarty: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles

PREFACE

Even during the global crisis which broke more famous financial institutions, the failure of Box Brothers was noisy. The private bank collapsed shortly after the arrest of Dame Philomela Box, Chief Executive Officer, on charges of fraudulent dealing. A warrant was also issued for her nephew, Colin Box. Press speculation that he had done a runner ended when his body was discovered in the boot of a burned-out Volvo on Havengore Island, Essex. Autopsy determined that Colin’s head had been sawn off and used as a football. No one has ever been charged with his murder, or those of two other bank officers found dead in the next six weeks.

Only after the CEO’s indictment could Box Brothers be called in print what it was, and always had been: the criminals’ bank. Founded in 1869, the family-owned business maintained premises in Moorgate, Gibraltar and Bermuda [1] …and reputedly, as Montacute Blore Box (1896–1953) was wont to boast, ‘in Hell!’

. For nearly a century and a half, Box Brothers provided financial services (no questions asked) to law-breakers great and small. Their client list ranged from underworld gangs (and, from the 1960s on, terrorist cells) with enormous turnovers to conceal to lowly smash-and-grab merchants with bloodied cash deposits to make. As their still-live website euphemistically has it, Box Brothers’ twenty-first-century speciality was ‘offshore wealth management’ — which is to say, getting the loot out of the country. The house’s oldest service was the most confidential and secure storage facility in the City of London — which is to say, a box to keep the jewels or paintings (or, in several cases, people) out of sight until the heat died down.

At the time of writing, the Moorgate premises remain under twenty-four-hour armed guard as suits and countersuits regarding access to the safety deposit vault (where it is rumoured the trophies of several famous, unsolved thefts are to be found) are argued. Or not… since it seems the management were not above dipping into the till to pay for Dame Philomela’s passion for airships or Colin’s white rap label [2] ‘Regardless of other crimes, anyone who founds a UK-based white rap label and signs up Danny Dyer should have his head kicked into an Essex marsh.’ — Charles Shaar Murray, Facebook update, November 16, 2008.

. Lawrence and Harrington Box, the founders, would have been aghast at the decline from the standards set in their day. Their simple philosophy was scrupulous honesty. Clients were expected to set aside their habitual larceny in dealing with the bank, just as the brothers made no moral judgement about business brought to them.

Before the crash, my dealings with Box Brothers were limited.

While my A History of Silence: Victorian Crimes Against and By Women [3] London: Virago and Emeryville, CA: Shoemaker and Hoard, 2004.

was in proof, my cat went missing. When I left for work, Crippen was locked in the flat. When I came home, the flat was still locked but Crippen was gone. The next day, my Female Serial Killers seminar was interrupted by a special messenger making a recorded delivery of a lawyers’ letter which suggested I delete any mention of Box Brothers from my forthcoming book. I first read ‘if the offending material is not removed, no further legal action will be taken’ as a mistyping. Then I saw ‘no further legal action’ did not mean ‘no further action’. When I got home, Crippen was back, with a triangle snipped out of her ear. The offending reference consisted of a footnote in a chapter about nineteenth-century brothelkeepers [4] An expansion of my article ‘Mrs Warren and Mrs Halifax: Controlling Male Desire and Female Economic Emancipation’, Victorian Studies, 41 (2), 1998. Considering the mentions, passim, of Mrs Halifax in the Moran manuscript, further research into this remarkable woman is a priority.

. I made the edit.

When Box Brothers fell, several hastily researched articles about the bank’s history appeared in the papers. Evidently, the bank no longer had the wherewithal to put pressure on journalists and historians. I assumed — not without Schadenfreude — that their in-house catnappers were busy avoiding larger, more dangerous animals. Widows and orphans and pension funds and small businessmen with accounts in Iceland run screaming to the government when their savings are in peril, but the sort of customer who banks with Box Brothers takes more direct action.

In July, 2009, I took a call in my office at Birkbeck College from Philomela Box’s private secretary, Henry Hassan.

‘Ms Temple, are you free to come into Dame Philomela’s office this afternoon for a consultation?’

‘On what?’ I asked.

‘Historical documents,’ he said.

Considering Crippen’s snipped ear, I was of a mind to tell Hassan where to file his historical documents. And to tell him it should be Professor Temple.

But it had been a boring week. The long summer vac was filled with faculty meetings about budget cuts. The only interesting PhD student I was supervising [5] Victoria Gorse, Gender in Asylums, 1890–1914. Ms Gorse’s thesis remains incomplete, and the student’s whereabouts unknown… though odd text messages purporting to be from her are received to this day. The last I had was ‘cha0s ra1nz!’.

was off working as a tour guide in Barcelona. So I agreed to visit the City.

Dame Philomela’s office was not in Holloway Prison. She was still in Moorgate. Windows smashed by an angry mob were boarded up. The building was guarded both by uniformed policemen and helmeted private security. A faction of anti-capitalist enthusiasts mounted a cosplay protest which had thinned over the months since the credit crunch started to bite. Ghost-masked young folks wore loose pyjamas decorated with broad arrows, and dragged about Jacob Marley chains of ledgers and strongboxes. Their slogans suggested they didn’t see Box Brothers as more criminal than any other bank.

Mr Hassan, the last loyal retainer, met me in a cavernous, dim reception room. Dustsheets were draped over the furniture. Loose wires showed where computers had once been plumbed in. Unfaded oblongs on the plush wallpaper marked the spots formerly taken by pictures which had walked out with suddenly unemployed staff. A cleaner had been arrested legging it down Silk Street with two Vernets and a Greuze in a Budgens ‘Bag for Life’.

I was ushered into an inner office.

A tall, thin woman came out from behind a desk to shake my hand. A red light flashed on her ankle bracelet.

‘Henry, get us espresso… if the plods haven’t taken the last of it along with every bloody thing else,’ said Dame Philomela. ‘I’ll have gin in mine, but the professor won’t, I’m sure.’

Mr Hassan retreated, backing out like a nervous courtier.

Dame Philomela’s office was hung with airship mobiles. She had a framed print of The Hindenburg disaster. On bookshelves where most bankers display leatherbound tomes of financial lore she had a complete set of Jeffrey Archer first editions. She was evidently a bit of a fan: in a photograph, she and Lord Archer wore matching flying helmets and her smile showed half a skull. I assumed he’d give her tips on how to get by in prison.

Dame Philomela was sixty. From experience with postgraduate students, I knew at once she was a functioning anorexic. She wore a tailored dark suit with a short skirt. Her long, straight black hair had a white streak — she must dye twice for the effect. Her only items of visible jewellery were a lapel-brooch in the shape of a dirigible and a discreet silver nose-stud.

Читать дальше

![Беар Гриллс - The Hunt [=The Devil's Sanctuary]](/books/428447/bear-grills-the-hunt-the-devil-s-sanctuary-thumb.webp)