Between 1970 and 1985, a 71 per cent decline in coastal-breeding Black-headed Gulls in the Republic of Ireland was reported, but the numbers there had recovered by the time of the 2000 census. It is possible that an appreciable proportion of the missing birds in 1985 had not, in fact, died, but had moved to new breeding sites not visited at that time.

The general impression from these censuses is that the numbers of breeding Black-headed Gulls in Britain and Ireland increased during most of the twentieth century, and then numbers showed little overall change in Britain between 1985 and 2000. The meagre and incomplete data available since then hints that numbers have been maintained.

The BTO Bird Atlas 2007–11 data, collected between 1968–72 and 2007–11, reported a reduction of 55 per cent in the number of 10 km squares in Britain and Ireland containing breeding Black-headed Gulls. Whether this reflects a decline in overall numbers is uncertain, as it could be the result of a trend towards fewer, larger colonies. Sample counts made at some coastal sites by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) show little evidence of a national change in numbers between 1986 and 2015, and this is supported by the national censuses in 1985 and 2000, which (although the earlier census was incomplete) did not suggest any major overall numerical changes within Britain and Ireland.

There has been a trend over time towards decreasing numbers of Black-headed Gulls breeding at inland sites, while numbers nesting at coastal sites have increased in England and Wales. However, this change does not seem to have occurred in Scotland. This movement probably reflects that birds breeding on coastal islands are often better protected from both humans and Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) than those breeding inland. The impact of the dramatic increase of Fox numbers in Britain in recent years is not frequently appreciated. Stephen Tapper (1992) found that numbers of this predator had increased fourfold between 1961 and 1990, and suggested that the effect of Fox predation on Black-headed Gull colonies may be greater and more widespread than that caused by American Mink (Neovison vison).

COLONIES

Colony sizes

The Black-headed Gull is a colonial breeder, nesting on a wide range of sites, including lakes, reservoirs, small moorland pools and tarns, marshes, sewage farms, clay pits, dunes, saltmarshes and industrial ponds. While numbers of nests in some colonies are easily counted, others are difficult to measure as the nests can be concealed by vegetation or lie on boggy ground, making access difficult or risking damage to the vegetation. Good vantage points do not exist near many colonies, and different methods are therefore needed here to estimate their size.

The basic unit used to measure the size of a colony is the number of nests, applying the realistic assumption that two adult birds are associated with each nest. In very large colonies, sampling of nest density has been used and then extrapolated across the total area of the colony as delineated from aerial photographs or detailed large-scale maps. At some sites, pair and hence nest numbers have been estimated through the less reliable method of counting numbers of birds in the air when disturbed and then using a conversion factor, such as dividing by 1.55. Most Black-headed Gull census counts have errors, which should be considered when making interpretations of the national status of the species and possible changes in abundance over time.

FIG 18. Part of the colony of Black-headed Gulls nesting with Sandwich Terns (Thalasseus sandvicensis) on Coquet Island, Northumberland. (John Coulson)

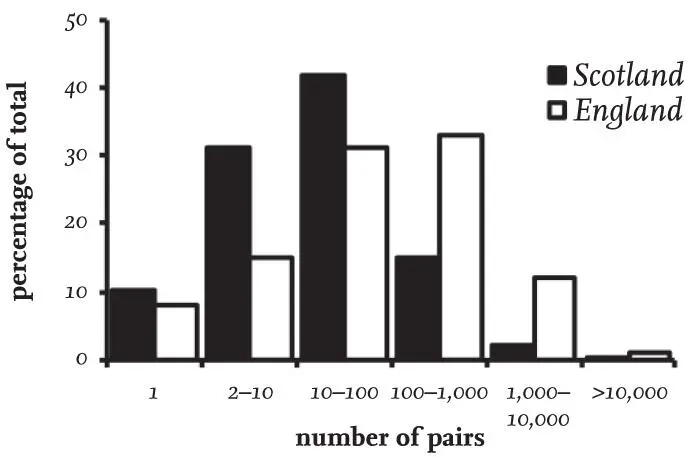

Data for years since 1980 on Black-headed Gull colony size recorded in the UK Seabird Colony Register allows for an in-depth assessment. While the species is essentially a colonial breeder, solitary breeding pairs on the day of counting comprised 10 per cent of the sites in Scotland and 8 per cent in England. Whether many of these pairs had been solitary for the entire breeding season is uncertain, because most of the nesting sites were visited by counters only once. It is possible that some single pairs were the sole remainders of a group present earlier in the breeding season that had suffered predation or disturbance, and had deserted the site prior to the observer’s visit. Single pairs of Black-headed Gulls can probably breed without the need of stimulus of other pairs, although when they do so, they nest late and their breeding success is usually low.

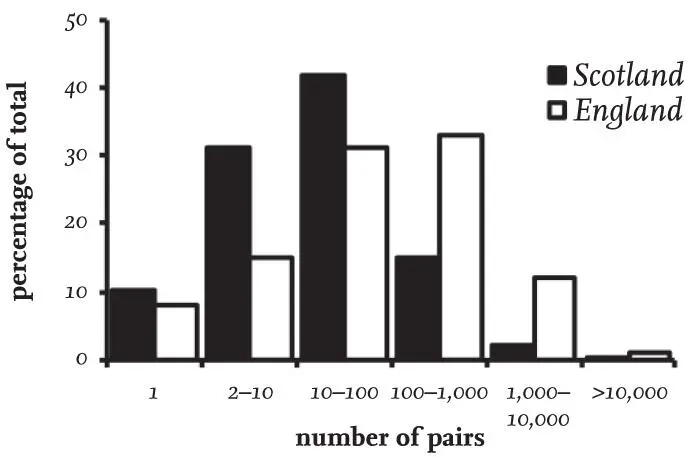

In Britain and Ireland, the numbers of pairs of Black-headed Gulls estimated at breeding sites (subsequently referred to as colonies for convenience, and including sites with single pairs) between 1980 and 2015 ranged from only one pair to more than 10,000 pairs. Overall, a third of colonies in Britain contained between 10 and 100 nesting pairs ( Fig. 19).

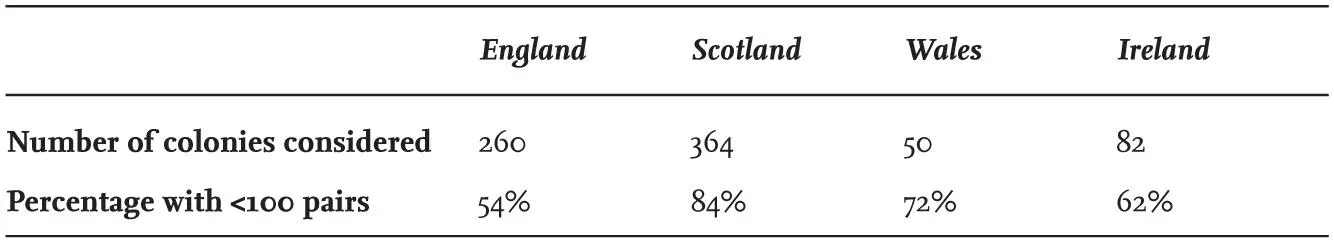

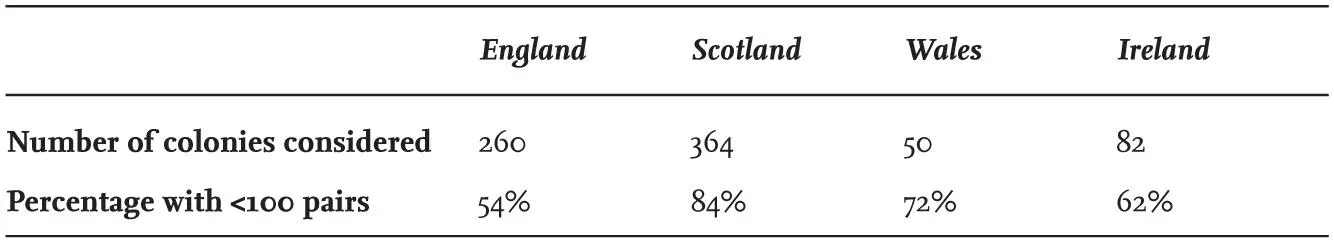

At the same time, the average size of colonies differed between Scotland and England, with 84 per cent in Scotland having fewer than 100 pairs ( Table 8), while the comparable figure for England was a third lower, at 54 per cent. Colonies with 100 to 1,000 pairs were twice as frequent in England than in Scotland, while colonies of more than 1,000 pairs formed 13 per cent of all sites recorded in England, but only 2 per cent of those in Scotland.

These differences reflect the type of nesting sites used in the two regions, with the majority in Scotland being inland on upland sites and usually associated with relatively small waterbodies, while in England large coastal colonies were more frequent and were sometimes extremely large. The distributions of colony sizes in Wales and Ireland were intermediate between those in England and Scotland, with 72 per cent of colonies in Wales and 62 per cent in Ireland having fewer than 100 pairs ( Table 8).

FIG 19. The size distribution of Black-headed Gull colonies (including sites with only one pair) in England and Scotland between 1980 and 2015, based on Seabird Colony Register data for 364 colonies surveyed in Scotland and 260 in England.

TABLE 8. The proportion of Black-headed Gull colonies in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland with fewer than 100 breeding pairs, based on data from 1980–2015. Sites with a single pair present have been included.

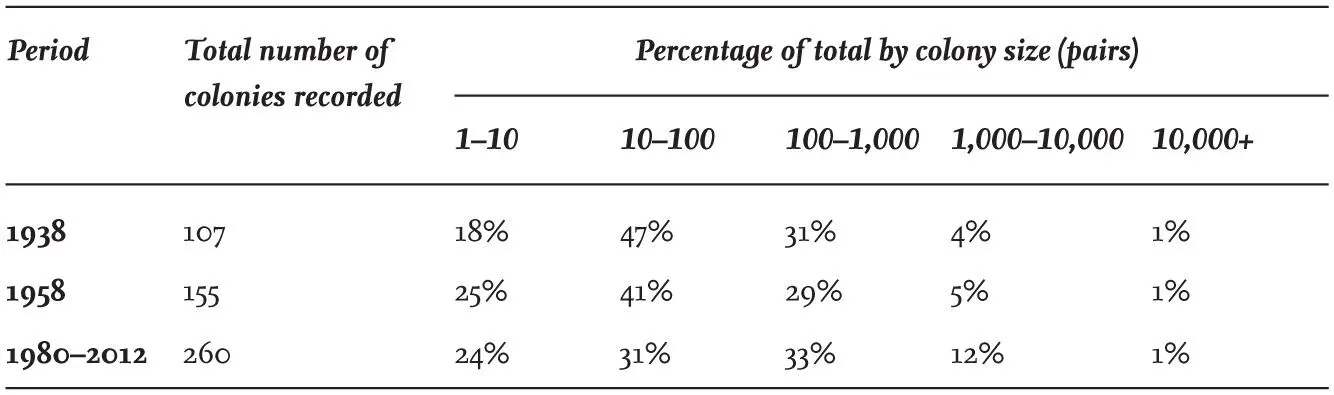

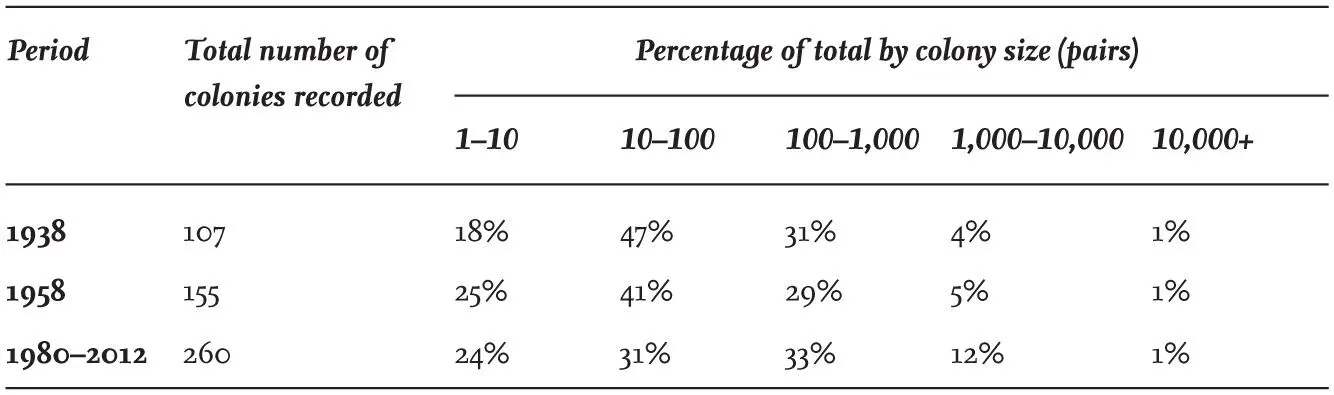

TABLE 9. The percentage of Black-headed Gull colonies of different sizes in England and Wales in 1938, 1958 and 1980–2012. Sites with only one pair are included.

A comparison between the size of colonies reported in the 1938 and 1958 censuses made in England and Wales, and more recent data collated in the Seabird Colony Register, show progressive changes in colony sizes over time ( Table 9). There has been an overall decrease in the proportion of colonies with fewer than 100 pairs since 1958, while the proportion and total numbers of large colonies with more than 1,000 pairs has more than doubled over the same period. Many colonies – particularly small ones in England and Wales – have disappeared for various reasons, including disturbance, predation and drainage, while others – particularly large ones – are now protected within nature reserves, although even a few of these have disappeared.

Читать дальше