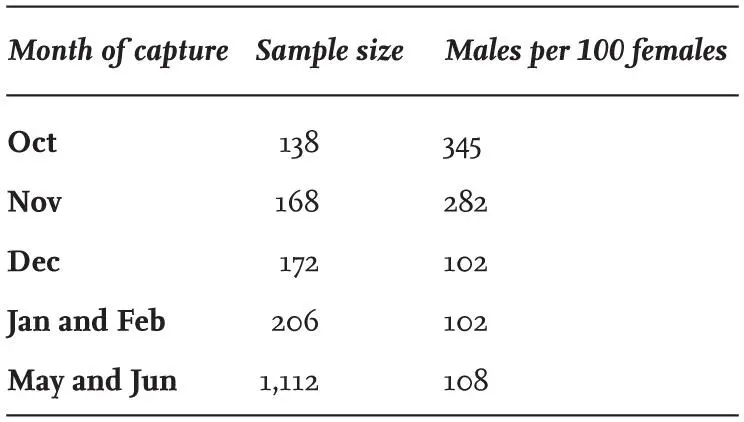

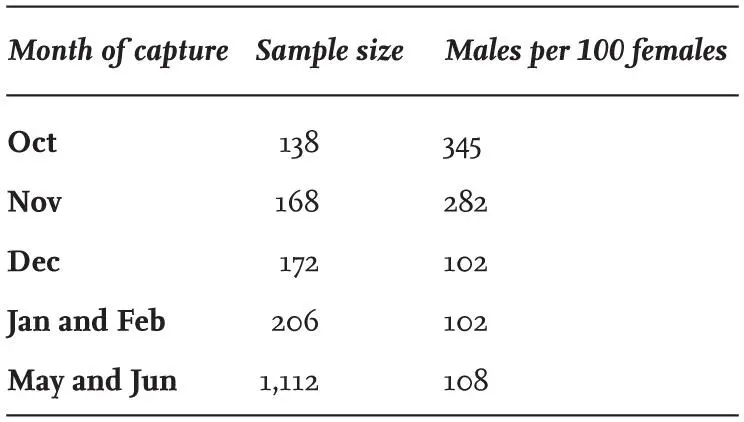

TABLE 13. The sex ratio of adult Black-headed Gulls cannon netted at landfill sites between October and February in north-east England, and near large colonies in northern England in May and June. Males were identified by a head and bill measurement of 82 mm or longer.

BREEDING BIOLOGY

Black-headed Gulls build their nest on the ground in areas with low-growing vegetation of varying density, ranging from sand dunes with much bare ground, to taller and floating vegetation around tarns and lakes. However, a few exceptions have been reported. At Seamew Crag, a small islet on Lake Windermere, Clive Hartley and Robin Sellers recorded several of the 50 pairs in the colony there nesting on top of low bushes over several years following 2009 (pers. comm.). In East Anglia in 1947, an entire colony numbering more than 300 pairs switched to nesting 2–3 m above ground level in young spruce trees, apparently in response to the flooding of their usual nest sites on the ground (Vine & Sergeant, 1948). Unlike some other gull species, there is only one old record of Black-headed Gulls nesting on a building, but in 2015 Robin Sellers found three small groups doing so, two near Perth and the other at Montrose, both in Scotland (pers. comm.).

Philopatry and colony faithfulness

Most Black-headed Gulls are two years old before they breed for the first time and a minority are a year older before they breed. Exceptionally, one-year-old individuals attempt to breed, although their success is very low. Many of those that have survived to maturity return to breed in the colony in which they hatched as chicks (called philopatry), but others move to other colonies, often some distance away. The high proportion returning to the natal colony indicates that the young birds retain a good memory of where they were reared. However, it is easier to find marked individuals that have returned to their original colony than those that have moved elsewhere and consequently the extent of philopatry is often exaggerated. A realistic estimate of the extent of philopatry is obtained by measuring the proportion of those ringed as chicks and have reached adult age that were recovered during the breeding season less than 20 km from their natal site. In the case of the Black-headed Gull, about 60 per cent of the young that survive to breeding age are philopatric and the remaining 40 per cent move to other colonies and in a few cases, across the North Sea, to breed on the Continent. There have also been exchanges of individuals between Ireland and Britain ( Fig. 34). Once adults have bred in a colony, their attachment to it becomes high, and at least 85 per cent of those surviving to the following year return to it to breed. The few adults that move elsewhere to breed are mainly from colonies that are in the process of being deserted, in some cases as a reaction to repeated nesting failure and the presence of mammalian predators.

FIG 34. Movements of more than 20 km of Black-headed Gulls ringed as chicks in Britain and Ireland and recovered in the breeding season when of breeding age. Many returned to breed at or near where they were reared, but a similar proportion apparently moved to other colonies. A few moved to the Continent to breed, mainly between northern France and Denmark, but one moved to Germany, another to Norway and a third to northern Sweden. Reproduced from The Migration Atlas (Wernham et al. 2002), with permission from the BTO.

Annual reoccupation of the colony

Black-headed Gull colonies are first visited by groups of adults in March each year. They arrive at irregular intervals during the morning, flying over the site without landing, and do not remain long at the colony or in the vicinity. Eventually, on one such visit some birds do land, but they exhibit a degree of nervousness and are easily disturbed. These visits become more frequent, but will be curtailed or prevented by cold and windy weather. As the days pass, the daily presence of the birds at the colony lasts much longer and spreads into the afternoon, but the colony is always vacated before sunset. The gulls usually leave by a synchronous ‘up’ or ‘panic’ flight, which sees them all suddenly rising high above the colony as if alarmed, yet without an obvious stimulus such as the appearance of a predator. As April progress, the amount of time the gulls spend at potential nest sites extends to the greater part of the day, but the colony is still deserted each night and reoccupied early in the morning, sometimes well before sunrise.

Pairs are formed early and courtship displays become common ( Fig. 35). In the meantime, nesting material is collected locally and brought in to the colony. Birds nesting in some coastal colonies often collect substantial and untidy quantities of brown seaweed, while those at inland sites collect dry grass locally and carry it to the selected nest site to construct the nest. More material is usually added to the nest during incubation. Colonies and nesting sites are usually close to water, and nests are often substantial structures that raise the eggs above the local water levels.

FIG 35. Female Black-headed Gull (right) courtship-begging for food from a male. (Norman Deans van Swelm)

The density of nests varies according to the size of the colony and the nature of the nesting site. Nests are 1–2 m or more apart where plant growth is sparse, but only 50 cm apart in dense vegetation, presumably because this tends to conceal the neighbouring pair, moderating the extent of aggression between close neighbours.

Eggs and incubation

Black-headed Gull eggs are brown with spots of a darker colour. They are laid in mid- to late April (the date of the first egg laid in different years at Ravenglass ranged between 12 April and 26 April), but even at this time the colony is still often deserted at night, with the adults moving to night roosts and leaving the early eggs unprotected. As clutches are completed and incubation begins, increasing numbers of birds remain in the colony throughout the night; it is at this point that predation by Foxes on incubating adults may occur.

In Britain, the peak of laying in Black-headed Gulls is reached at the end of April or in early May, which is earlier than in other gull species breeding here. Fig. 36shows the date distribution for the first eggs in each clutch recorded by Ian Patterson at Ravenglass (1965). There is considerable laying synchrony by the majority of pairs, but there is often a distinct tail or a secondary late peak of birds that re-lay after losing their first clutch or delay laying owing to inexperience.

The typical clutch comprises three eggs, although two-egg clutches are common. Occasionally, four-egg clutches occur, but whether these are laid by only one female has not been investigated. Late-laying birds produce clutches of just one or two eggs. Average clutch size within a colony varies considerably, from 2.3 to 2.8 eggs. Nils Ytreberg (1956) recorded a high average of 2.9 eggs from 411 nests in Norway, but in a later year reported a smaller average of 2.62 eggs based on a sample of 100 nests (Ytreberg 1960). The average clutch size tends to be lower in years when laying starts late, such as in small colonies and those further north and in the uplands. Eggs are laid at variable times throughout the day and the interval between eggs is usually about two days.

Читать дальше