Unplanned shutdowns also happen for a variety of reasons, all of which are bad. An unplanned shutdown could be caused by a power outage, a broken piece of equipment, a strike, or a new government regulation. An unplanned shutdown also can be the result of running out of raw materials. You can’t make a product unless you have the components that go into it.

The other kinds of unplanned shutdowns are hard to predict and control, but you can easily prevent shutdowns due to a lack of raw materials by maintaining inventory. As a result, many manufacturing operations managers prefer to have extra inventory as an insurance policy — to make sure that they never run out of materials that would cause an unplanned shutdown. That extra inventory, of course, ties up working capital and eats up space.

Lean Manufacturing techniques help minimize the number of unplanned shutdowns caused by inventory stockouts while minimizing the amount of inventory in a supply chain.

One of the key elements of Lean Manufacturing is the use of a kanban for inventory replenishment. A kanban is an automatic reorder trigger for inventory. Containers can be used as kanbans to trigger inventory replenishment at each step in a supply chain, for example. When the last item is pulled from a container, it’s time to order a new container. This process provides a smooth, step by step flow of inventory. When you use a kanban system, there’s no way for inventory to be pushed down to the next step in a supply chain; it can only be pulled by the downstream kanban.

Toyota developed a unique approach to managing the flow of products through its manufacturing process, allowing the company to minimize inventory costs and unplanned shutdowns. This approach involves tools and techniques that are collectively known as the Toyota Production System. As other companies adopted this approach, it became known as the Lean Manufacturing technique because it reduces the inventory fat in a supply chain. Chapter 4includes more information about Lean.

Toyota developed a unique approach to managing the flow of products through its manufacturing process, allowing the company to minimize inventory costs and unplanned shutdowns. This approach involves tools and techniques that are collectively known as the Toyota Production System. As other companies adopted this approach, it became known as the Lean Manufacturing technique because it reduces the inventory fat in a supply chain. Chapter 4includes more information about Lean.

Procurement versus logistics

Procurement teams look for ways to get the same materials at lower cost. Two common ways reduce costs are to buy in larger quantities and to buy from a supplier in a low-cost region. Both of these options are likely to provide a lower cost per item, but they also can have the unintended result of increasing logistics costs.

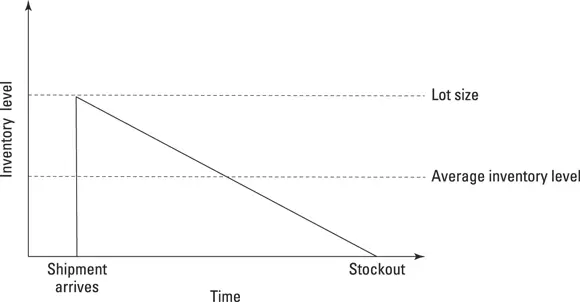

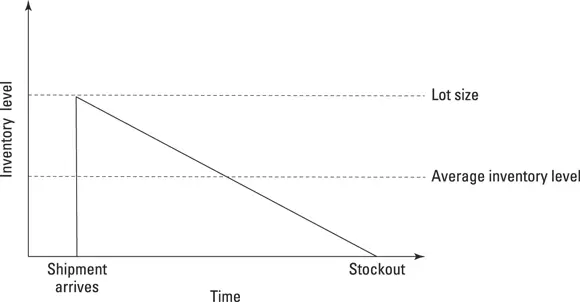

For one thing, increasing the amount of material that you order each time, called the lot size, also increases the amount of inventory that you have. You start with no inventory; then you receive a shipment of whatever lot size you agreed to purchase from your supplier. You gradually use that inventory to make products, or sell that inventory to customers, until you have no inventory left. Eventually, you run out of inventory again. Over that period, how much inventory did you have on average? The answer is that the average amount of inventory — and the average amount of working capital that you had tied up in inventory — is half your lot size. Therefore, on average, the more you order at one time, the more inventory you end up with. You can see how this process works in Figure 3-4.

Ordering in larger quantities also means that you need to have extra space to store inventory and more people to manage it. Although increasing the lot sizes may get you a lower cost per unit, it could end up increasing your inventory costs even more.

A similar problem comes up when you consider suppliers located farther away. The price per unit may be lower, but the increased transportation costs can eat up all those savings and then some. Shipping items a longer distance can also force you to buy in larger quantities. The farther you have to move something, the more things can go wrong along the way. To compensate for this risk, you’ll probably need to — yep, you guessed it — increase inventory.

FIGURE 3-4:Average inventory level.

The way to balance the priorities of purchasing and logistics is to use a total-cost analysis approach to sourcing decisions. Make sure that you’re evaluating all the elements that will cost you supply chain money. You may find that a nearby supplier that can deliver in small batches and at a low transportation cost is a much better option than a lower-cost supplier in a distant location that would require you to spend more money on transportation and inventory.

Chapter 4

Optimizing Your Supply Chain

IN THIS CHAPTER

Mapping your supply network

Mapping your supply network

Driving process improvements

Driving process improvements

Managing supply chain projects

Managing supply chain projects

Depending on the product or service that you’re selling, you probably have many alternatives to choose among when designing your supply chain. You may have choices of how and where to buy your materials or make your products. Perhaps you can even choose different ways to deliver your products to your customers. This chapter discusses techniques to optimize your supply chain to ensure that you’re creating the most value, in the most sustainable way, for you and your customers. It also talks about how to implement improvements to your supply chain through cross-functional projects.

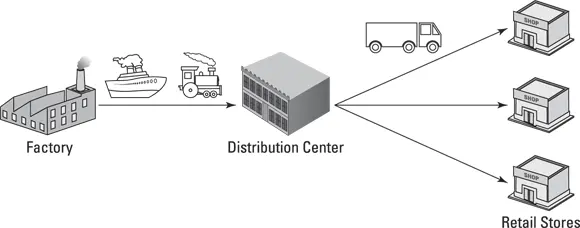

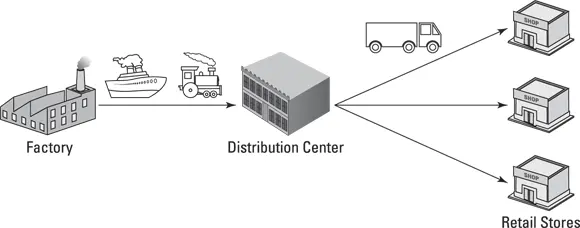

It’s often useful to think about your supply chain as a network. Networks are made up of nodes and links. As Figure 4-1 shows, every stop that a product makes between raw materials and a customer is a node of the network. A factory is a node; so are a warehouse, a distribution center, and a retail store. Nodes are connected by links. Generally speaking, links are forms of transportation, such as a ship, a railroad, a truck, or a drone. Products move through a supply chain, flowing through links and stopping at nodes.

FIGURE 4-1:Nodes and links in a supply chain.

Your goal for any supply chain is to deliver maximum value at the lowest cost. One way to achieve this goal is to change the nodes and the links. Perhaps you can lower the costs of your raw materials by sourcing them from a different supplier, which means you’d be changing one of your nodes. Changing a node also means changing the links that connect that node to the rest of your supply chain.

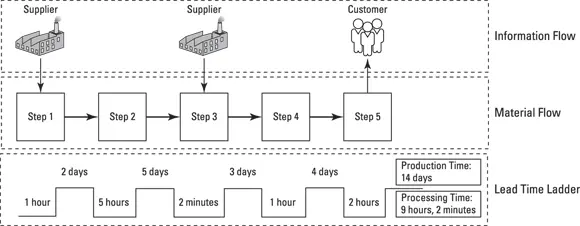

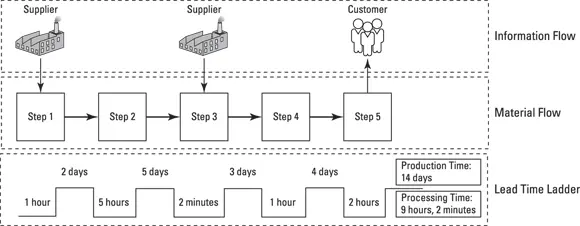

Making changes in the links and nodes is called network optimization . One approach to network optimization is called value-stream mapping (VSM). Figure 4-2 shows a simple example of a VSM. The more of your supply chain that you’re trying to optimize, the larger — and more complex — your VSM becomes.

FIGURE 4-2:Example VSM.

VSM is an important part of a Lean professional’s tool kit, as you see in the next section, but network optimization can be done on a larger scale with sophisticated mathematical analysis. Several supply chain software platforms are available to help with analyzing supply chain flows, starting with spreadsheets and moving up to complex supply chain modeling tools. In addition to factoring in the costs for buying materials and transporting them between nodes, some network optimization tools can factor in variables such as supplier performance and the effects of tariffs and taxes. The sections on supply chain modeling software and business intelligence software in Chapter 12discuss this topic in more detail.

Читать дальше

Toyota developed a unique approach to managing the flow of products through its manufacturing process, allowing the company to minimize inventory costs and unplanned shutdowns. This approach involves tools and techniques that are collectively known as the Toyota Production System. As other companies adopted this approach, it became known as the Lean Manufacturing technique because it reduces the inventory fat in a supply chain. Chapter 4includes more information about Lean.

Toyota developed a unique approach to managing the flow of products through its manufacturing process, allowing the company to minimize inventory costs and unplanned shutdowns. This approach involves tools and techniques that are collectively known as the Toyota Production System. As other companies adopted this approach, it became known as the Lean Manufacturing technique because it reduces the inventory fat in a supply chain. Chapter 4includes more information about Lean.

Mapping your supply network

Mapping your supply network