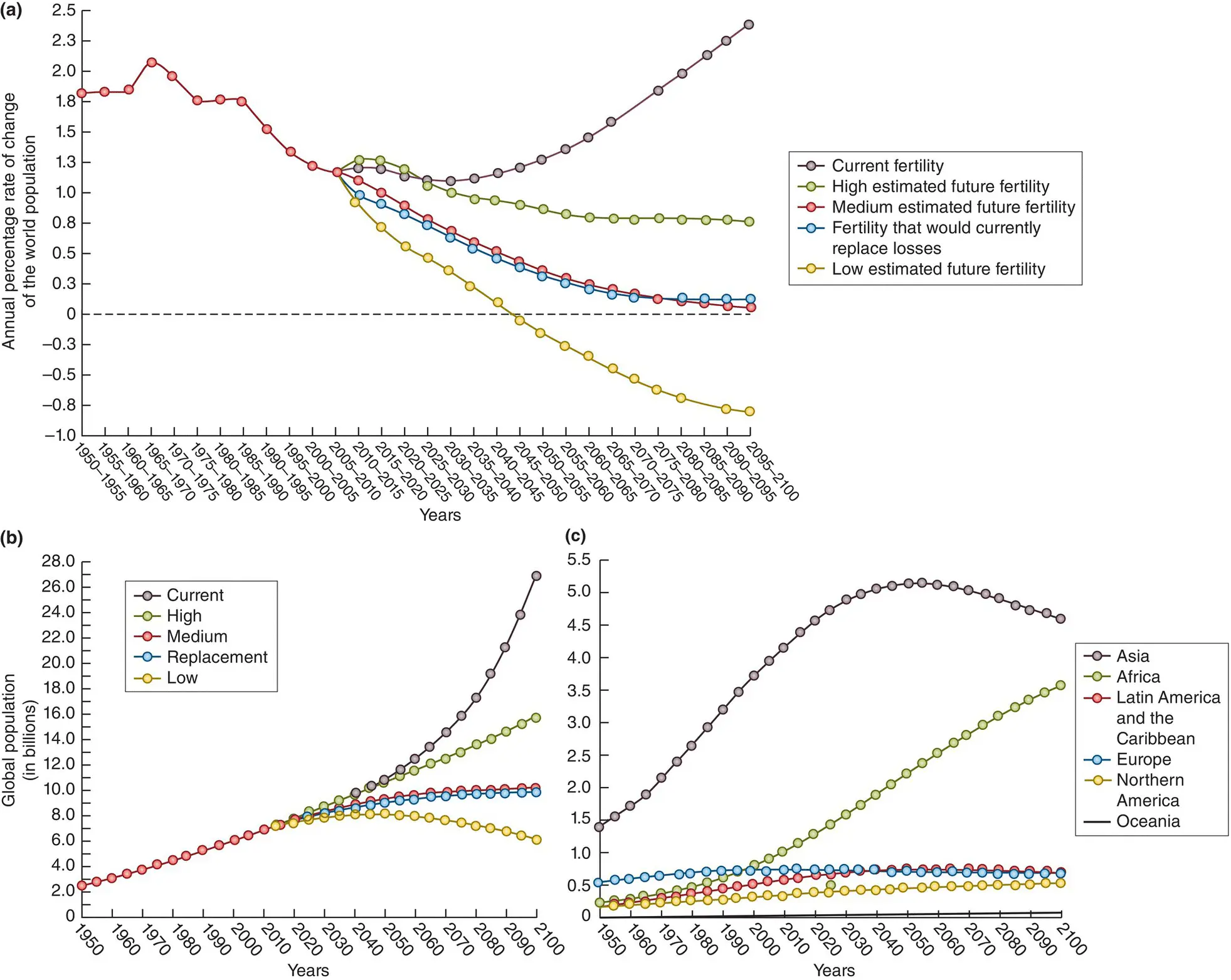

Source : After Cohen (1995).

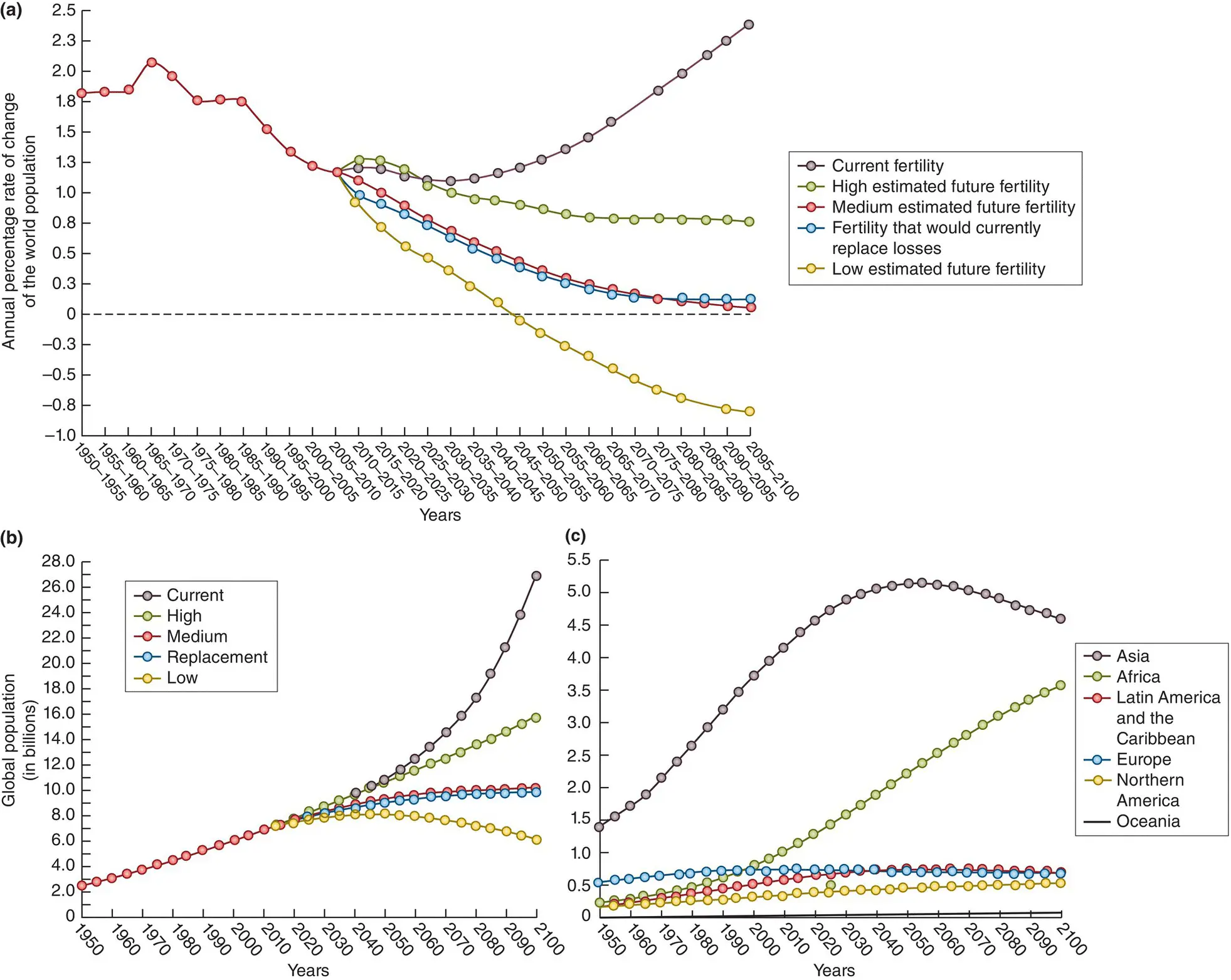

The generally accepted explanation, though probably not the whole story, is that the transition is an inevitable consequence of industrialisation, education, and general modernisation, leading first, through medical advances, to the drop in death rates, and then, through the choices people make (such as delaying having children) to the drop in birth rates. Certainly, when we consider the populations of the different regions of the world together, there has been a dramatic decline from the peak population growth rate of about 2.1% per year in 1965–70 to around 1.1–1.2% per year today ( Figure 5.19a).

Figure 5.19 What happens to the global human population size depends on future fertility patterns.(a) The average annual percentage rate of change of the world population observed from 1950 to 2010, and projected forward to 2100 on the basis of various assumptions about future fertility rates. (b) The estimated size of the world’s population from 1950 and 2010 and projected forward to 2100 on the basis of various assumptions regarding fertility rates. (c) The estimated size of the populations of the world’s main regions from 1950 and 2010 and projected forward to 2100 assuming ‘medium’ fertility rates.

Source : After United Nations (2011).

a global carrying capacity?

It seems clear, then, that the rate of human population growth is slowing not simply as a result of intraspecific competition, but as a result of the choices people make. Nonetheless, if current trends continue, we might hope that the size of the global human population could level off and approach what, in terms of intraspecific competition, we would call a global carrying capacity. This in turn raises the question of what a reasonable global carrying capacity would be. Estimates have been proposed over the last 300 years or so. They vary to an astonishing degree. Even those suggested since 1970 span three orders of magnitude – from 1 to 1000 billion. To illustrate the difficulty of arriving at a good estimate, we can look at a few examples (see Cohen, 1995 , 2005 for further details).

In 1679, van Leeuwenhoek estimated the inhabited area of the Earth as 13 385 times larger than his home nation of Holland, whose population then was about one million people. He assumed all this area could be populated as densely as Holland, yielding an upper limit of roughly 13.4 billion. In 1967, De Wit asked how many people could live on Earth if photosynthesis was the limiting factor (but neither water nor minerals were limiting) and suggested 1000 billion, though if people wanted to eat meat or have a reasonable amount of living space the estimate would be lower. By contrast, Hulett in 1970 assumed levels of affluence and consumption in the USA were optimal for the whole world, and he included requirements not only for food but also for renewable resources like wood and non‐renewable resources like steel and aluminium. He suggested a limit of no more than 1 billion. Kates and others made similar assumptions using global rather than US averages. They estimated a global carrying capacity of 5.9 billion people subsisting on a basic diet (principally vegetarian), 3.9 billion on an ‘improved’ diet (about 15% of calories from animal products), or 2.9 billion on a diet with 25% of calories from animal products.

As Cohen (2005) has pointed out, most estimates have relied heavily on a single dimension – biologically productive land area, water, energy, food and so on – when in reality the impact of one factor depends on the value of others. Thus, for example, if water is scarce and energy is abundant, water can be desalinated and transported to where it is in short supply, a solution that is not available if energy is expensive. And as the examples above make clear, there is a difference between the number the Earth can support (the concept of a carrying capacity we normally apply to other organisms) and the number it can support at an acceptable standard of living. It is unlikely that many of us would choose to live crushed up against an environmental ceiling or wish it on our descendants.

what is the ‘human population problem’?

Our difficulties in defining a global carrying capacity raise a deeper difficulty. What is ‘the human population problem’? It may be simply that the present size of the global human population is unsustainably high – greater than the (presently unknown) carrying capacity. Or it may be not the size of the population but its distribution over the Earth that is unsustainable. Crowding as much as population size is the problem. As we have seen, the fraction of the population concentrated in urban environments has risen from around 3% in 1800 to more than 50% today. Each agricultural worker today has to feed her‐ or himself plus one city dweller. By 2050 that will have risen to each worker feeding two urbanites (Cohen, 2005). Or perhaps it is not the size but the age distribution of the global population that is unsustainable. In developed regions, the percentage of the population over 65 rose from 7.6% in 1950 to 12.1% in 1990. This proportion is now increasing faster still, as the large cohort born after World War II passes 65. Or finally it may not be that resources are limited but that their uneven distribution is unsustainable. Competition may be unbearably intense for some, while for others density‐independence prevails. In 1992, the 830 million people of the world’s richest countries enjoyed an average income equivalent to US$22 000 per annum. The 2.6 billion people in the middle‐income countries received $1600. But the two billion in the poorest countries got just $400. These averages themselves hide other enormous inequalities.

Of course, the human population problem, just like the problem in any crowded population, is not simply one of intense intraspecific competition for limited resources. Individuals in poor condition may be more vulnerable to predation and parasitism, and the spread of parasites may itself be enhanced. We return to the ways in which the abundances of populations are determined by the combination of forces acting on them in Chapter 14.

inescapable momentum

Finally we can ask what would happen if it were possible to bring demographic transition to all countries of the world so birth rates equalled death rates and population growth was zero. Would the population problem be solved? The answer is no, for at least two important reasons. We saw in Chapter 4that the net reproductive rate of a population is a reflection of age‐related patterns of survival and birth, but these patterns also give rise to different age structures within the population. If birth rates are high but survival rates low (‘pre‐transition’), there will be many young and relatively few old individuals in the population. But if birth rates are low and survival rates high – the ideal to which we might aspire post‐transition – relatively few young, productive individuals must support the many who are old, unproductive, and dependent: an aspect of the problem that we noted above.

In addition, even if our understanding was so sophisticated and our power so complete that we could establish equal birth and death rates tomorrow, would the human population stop growing? The answer, once again, is ‘No.’ Population growth has its own momentum, and even with birth rate matched to death rate, it would take many years to establish a stable age structure, while considerable growth continued in the meantime. According to projections by the United Nations, even with low fertility the world’s population will grow from slightly more than seven billion today to more than eight billion by 2050 ( Figure 5.19b). There are many more babies in the world now than 25 years ago, so even if birth rate per capita drops considerably now, there will still be many more births in 25 years’ time than now, and these children, in turn, will continue the momentum before an approximately stable age structure is eventually established. As Figure 5.19c shows, it is the populations in the developing regions of the world, dominated by young individuals, that will provide most of the momentum for further population growth.

Читать дальше