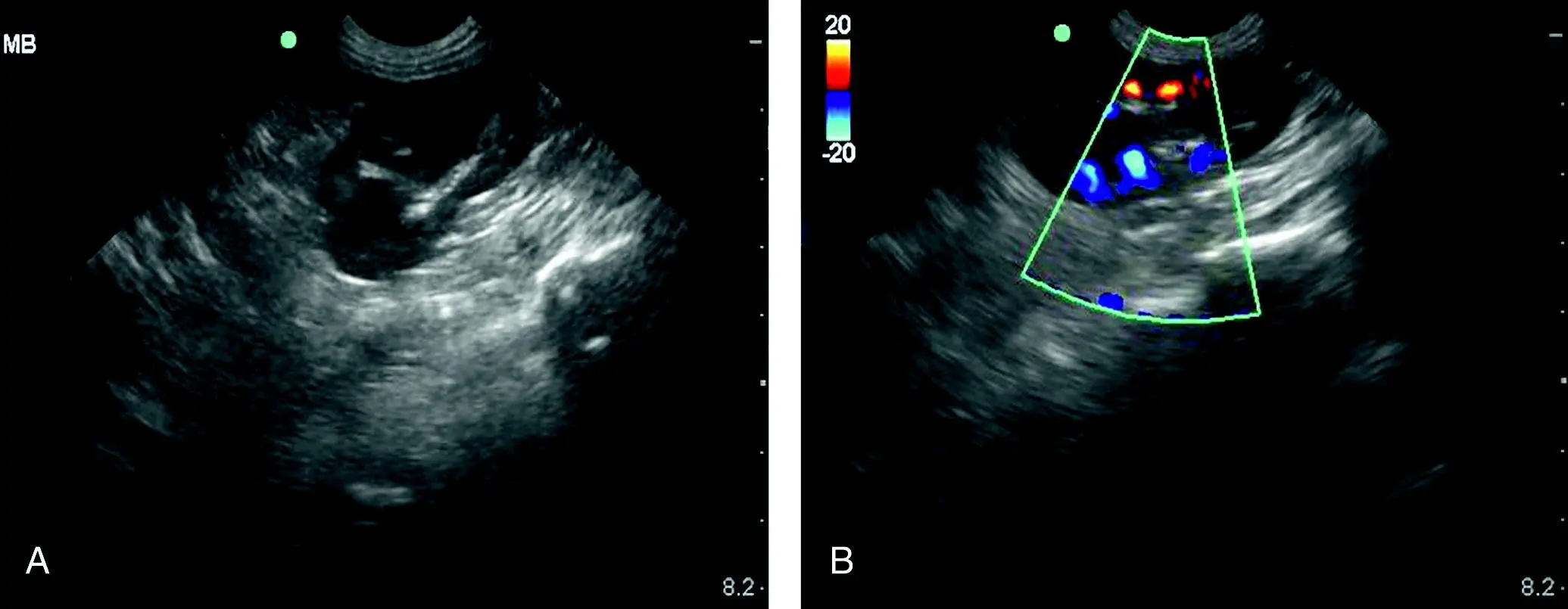

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Pearl:Although abdominal radiography is typically a low yield diagnostic test in bluntly traumatized patients for abdominal effusion, radiography should always be part of the standard work‐up in penetrating trauma.

Pearl:AFAST often misses clotted blood, which is a common feature of penetrating trauma, because the echogenicity of clots is similar to soft tissue. The use of color flow Doppler can be helpful because clotted blood has no blood flow.

Pearl:Serial AFAST exams increase sensitivity for the detection of intraabdominal injury in penetrating trauma suspects and should be routinely performed four hours post admission (sooner if unstable or questionable) and then as often as needed when surgical injury is still possible, including up to five days or more post injury.

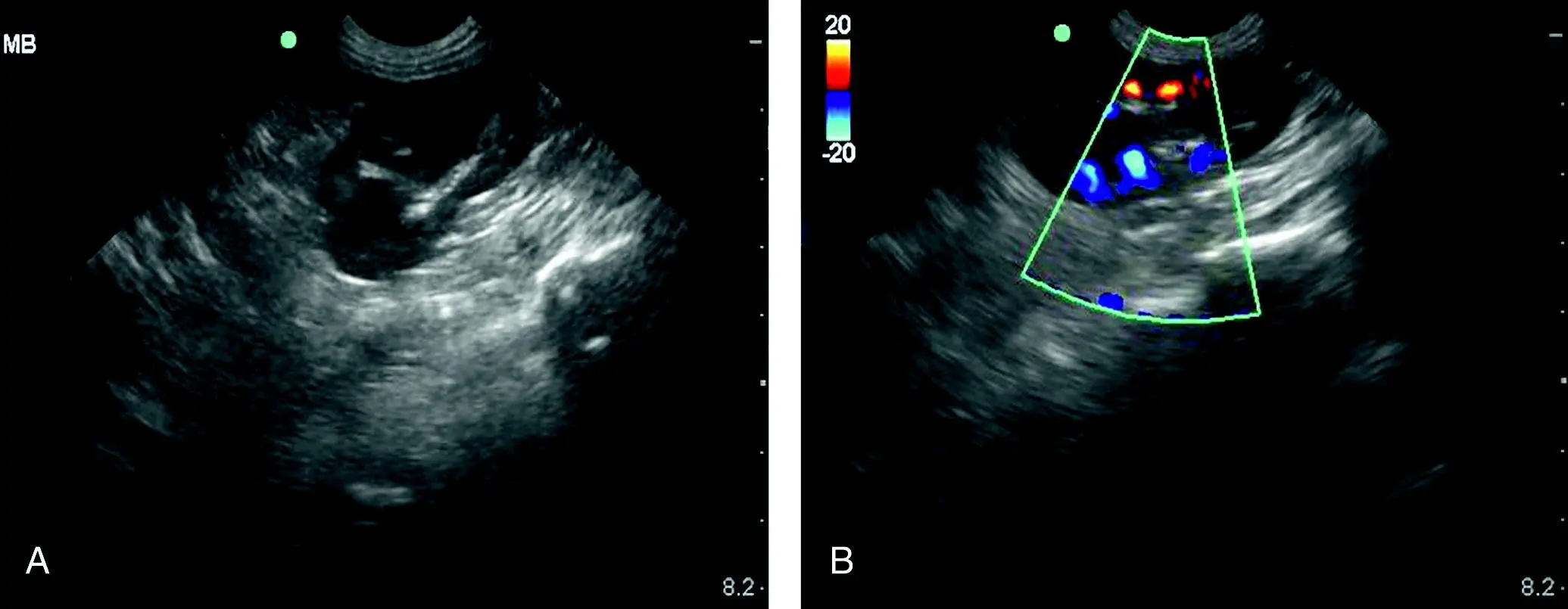

Figure 7.7. Evaluating for blood flow of the left kidney at the (SR) view. In (A) is a B‐mode image followed by color flow Doppler in (B) showing pulsatile flow. In penetrating injury, especially bite wounds over the lumbar region, or in animals which were shaken by their attacker, renal injury and avulsion are possible. It is a good habit to apply color flow Doppler routinely in these at‐risk cases, especially prior to exploratory surgery to help decision making by the surgeon for salvaging or removing the kidney.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

How Long Does It Take for Cavitary Bleeding to Resolve?

There are no veterinary studies that have established this definitively, but author experience and discussion among colleagues suggest that we should expect cavitary bleeds (peritoneal cavity, pleural cavity, pericardial sac) to resolve (or be very minimal in AFS) within 48 hours once the bleeding stops or after coagulopathy has been corrected (and remains corrected). We call this the “AFAST‐TFAST 48‐hour rule.”

Save All Cavitary Hemorrhage

It is important to harvest all cavitary hemorrhage cleanly into a collection apparatus as basic as clean syringes. The blood in the majority of cases will be naturally defibrinated in both dogs and cats. The collected cavitary hemorrhage may be administered without added anticoagulant through an inline blood filter to prevent administration of blood clots back to the patient (Higgs et al. 2015; Robinson et al. 2016; Cole and Humm 2019).

The question is sometimes posed regarding the older anemic hemoabdomen dog in a situation in which there are no resources for blood transfusion administration and whether leaving the blood in the abdominal cavity is acceptable. The argument is that by leaving the intraabdominal blood, the patient has the benefit of resorbing the cavitary blood postoperatively, and common sense should always prevail in the quest to improve the probability of patient survival. However, when possible, “dry the abdomen” to better interpret the clinical relevance of postoperative effusions.

How Long Does It Take for Lavage Fluid to be Resorbed?

A fascinating question because, in contrast to cavitary blood that is resorbed quite rapidly within the “AFAST‐TFAST 48‐hour rule,” lavage fluid lasts much longer (several days) in the author's experience. Thus, our recommendation is always “dry the abdomen” before abdominal closure using suction and running lap sponges through the left (mesocolon) and right (mesoduodenum) sided abdominal “gutters.” Drying the abdomen gives you a negative AFS (AFS of 0) post‐operatively and helps you better interpret the finding of free fluid post‐procedure. Moreover, neutrophils work much more effectively in a “dry abdomen” environment than one bathed in lavage fluid.

Pearl:Expect abdominal cavitary blood to be resorbed with decreasing AFS and be nearly resolved or at an AFS of 0 within 48 hours – the “AFAST‐TFAST 48‐hour rule” – once bleeding has stopped.

Pearl:Spend an extra few minutes to suction and “dry the abdomen” with lap sponges prior to closure. Neutrophils function better, and your patient has an AFS 0 prior to closure, which helps to interpret positive AFS postoperatively.

Cats Don’t Survive Large‐Volume Traumatic Bleeds

AFAST and the AFS system were prospectively studied in 49 traumatized cats. Although 17% of cats had positive fluid scores, feline “large‐volume bleeders” were almost nonexistent and those with an AFS of 3 and 4 died during triage or were dead on arrival and not enrolled (Lisciandro 2012). Originally, the conclusion was that AFS was less reliable in cats, but several years of experience suggest that AFS for bleeding works just as well in cats. However, bluntly traumatized cats generally do not survive large‐volume bleeds as dogs might (Mandell and Drobatz 1995; Lisciandro 2012). This is likely because the canine spleen serves as a large reservoir of blood whereas the feline spleen does not. Moreover, cats have over the years presented with “soft” positives at multiple AFAST views that would be better scored as a ½ rather than a full 1. The modification of the AFAST‐applied AFS system thus recategorizes more accurately these feline cases as “small‐volume bleeders” ( Figure 7.8).

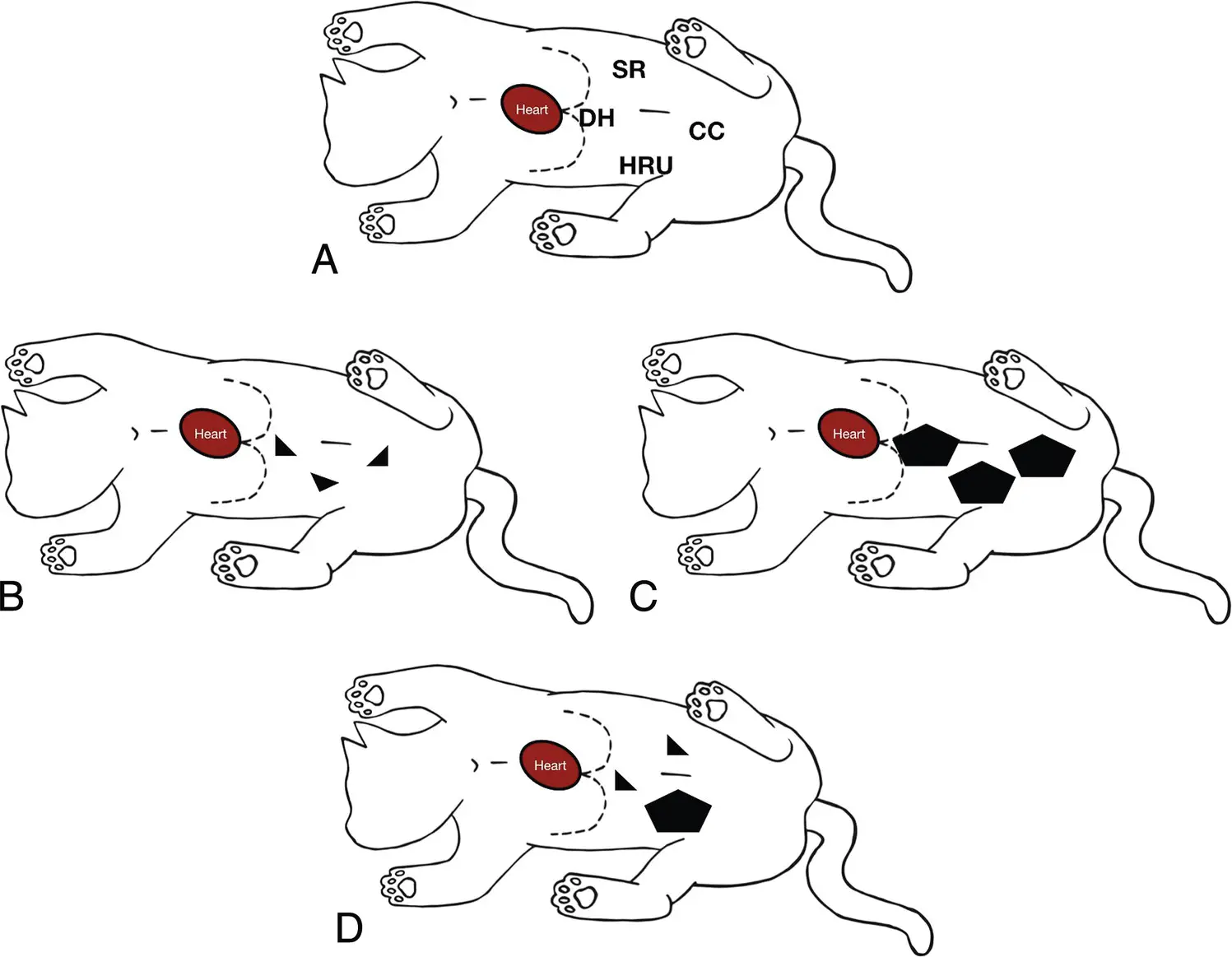

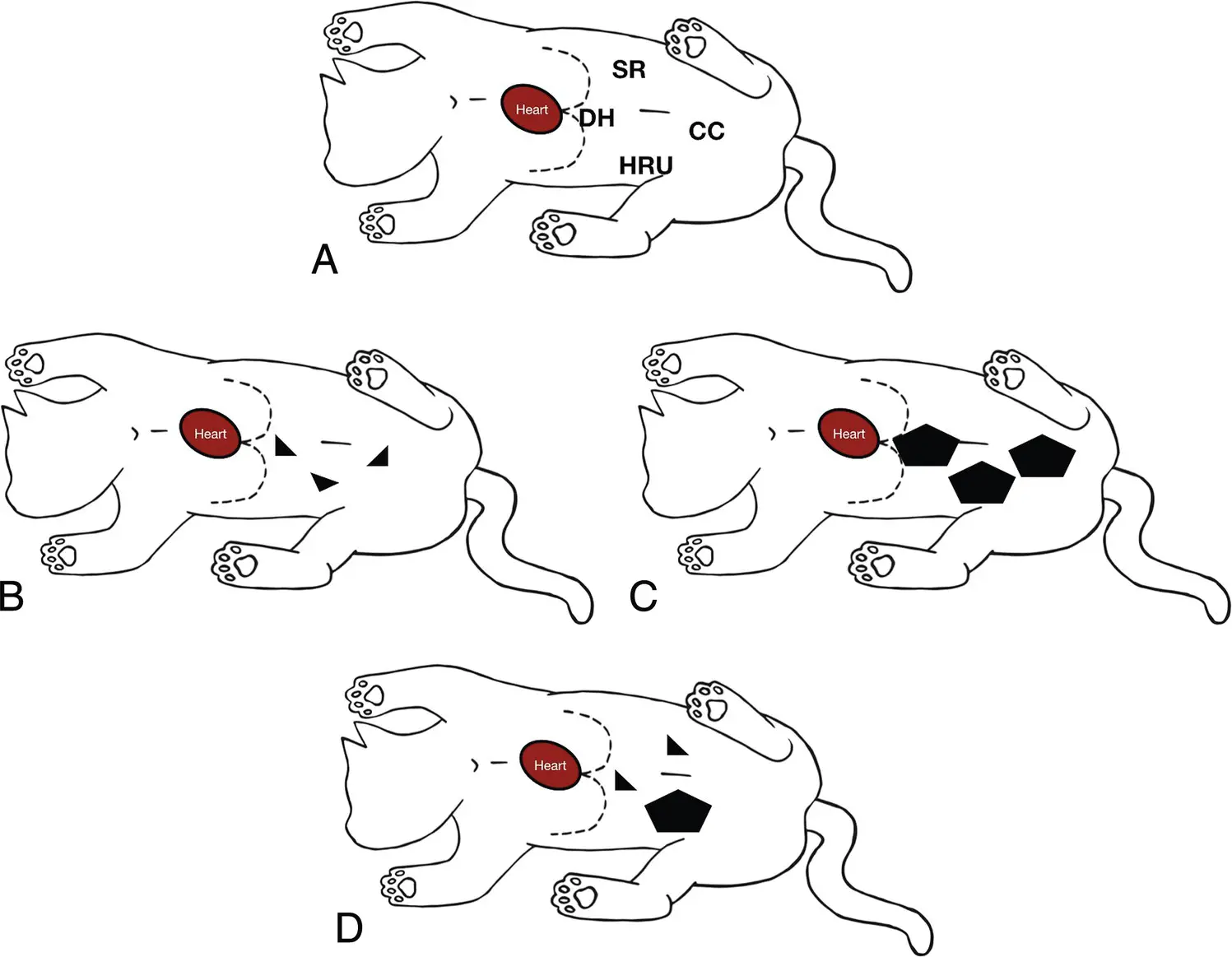

Figure 7.8. Example in a cat using the modified AFS system. (A) AFAST in right lateral recumbency and the four AFAST views used for the AFS. In (B) small triangulations (½ + ½ + ½) are found at three of the four views which calculates as an AFS of 1.5, a “small‐volume bleeder/effusion.” In (C) there are larger pockets of free fluid (1 + 1 + 1) at the same three AFAST views as in (A) and the AFS calculates as 3, a “large‐volume bleeder/effusion.” In (D) there are small triangulations at the DH and SR views and a larger pocket at the HRU view with a calculated AFS of 2 (½ + ½ + 1), a “small‐volume bleeder/effusion.” The same concept is applied to dogs.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX. Illustration by Hannah M. Cole, Adkins, TX.

Pearl:Cats with automobile‐induced traumatic hemoabdomen are often nonsurvivors before making it to veterinarians because they cannot compensate as dogs do and because of their smaller size, making injury more severe and lacking a splenic blood reservior. Free fluid on AFAST in surviving cats (>12–24 hours) is more likely to be urine than blood.

Importance of Recording Locations of Where Patients are Positive

It is imperative to not only record the AFS but also locations of where the patient is positive and negative. This is important because the locations of AFAST‐positive views in lower‐scoring “small‐volume bleeders” may be helpful for the localization of the bleeder ( Table 7.4). For example, consider a hit‐by‐car dog or cat with an AFS of 1 at the AFAST DH view that continues to bleed with an increase in AFS to 3 or 4 and that despite blood transfusions becomes a surgical case. Logic would dictate that the source of intraabdominal bleeding is likely associated with the liver and its vasculature. This information would potentially better prepare the surgeon for the anticipated type of injury, such as liver laceration, hepatic venous or vena caval injury, and for the needed procedure(s) as well as relevant resources. On the other hand, in the same trauma scenario the AFS 1 is positive at an AFAST view further caudally, such as the CC or HR umbilical view, and now logic would dictate that the source of bleeding would be more likely intestinal tract or spleen. Thus, the definitive procedure would likely be less technically challenging than a liver laceration or vascular hepatic injury.

Читать дальше