Consistently Maintaining the Screen Orientation of Head to the Left and Tail to the Right

When imaging in longitudinal and sagittal planes, including short‐ and long‐axis views of the heart, maintain the head to the left and tail to the right on the screen. If the area of interest is to the left of the screen, you learn to slide or rock toward the patient's head to center the image and vice versa if to the right of the screen, slide or rock toward the patient's tail whether you are doing AFAST, TFAST or Vet BLUE (see Figure 1.6). In human medicine, physicians performing cardiac FAST and POCUS examinations will not necessarily reverse orientation, but stay consistent with all other imaging, with cranial to the left and caudal to the right of the screen (Walker and Mohabir 2014). I like to call this the “rogue way” in which to capture echocardiography views, but maintaining orientation whatever the region of interest is advantageous for localizing abnormal findings, and the noncardiologist doesn’t have to do any mental spatial adjustments because the cardiac ultrasound orientation is now the same as everywhere else (abdomen and lung).

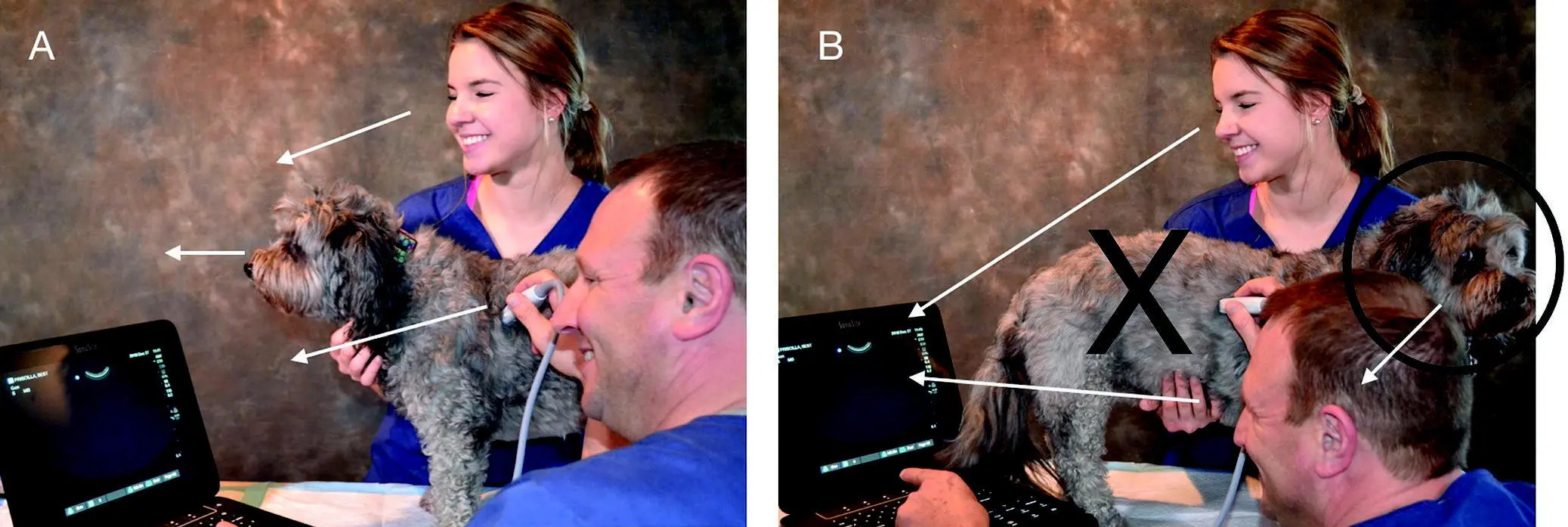

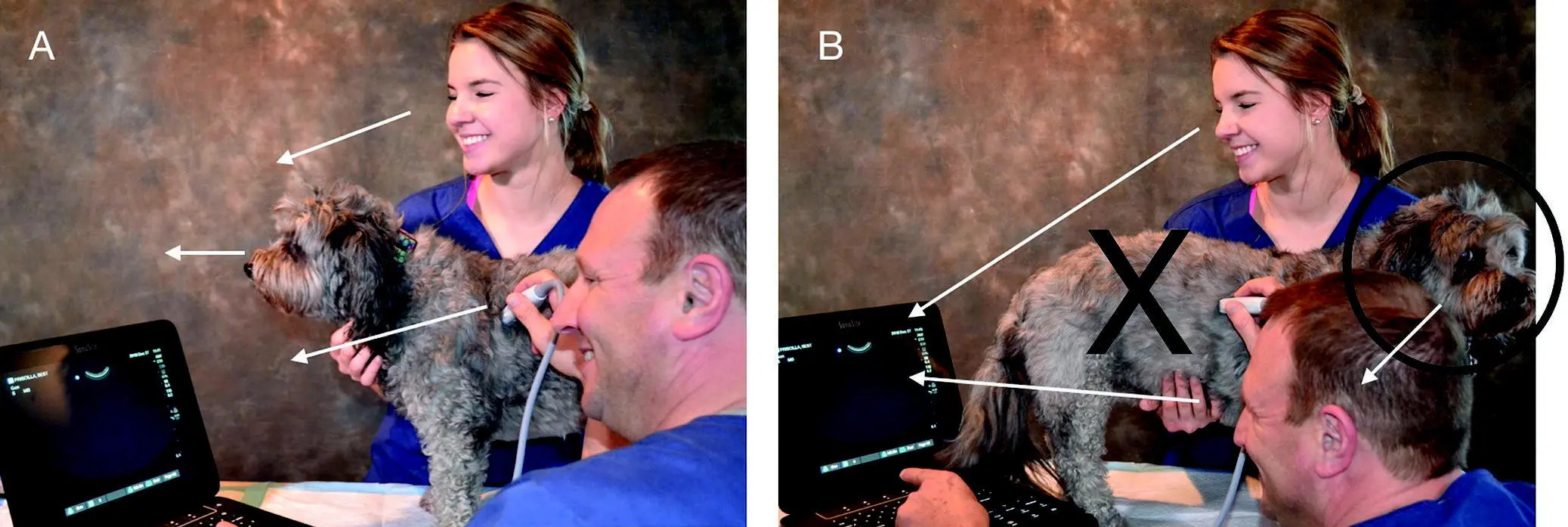

Figure 5.3. Best practice is the head of the patient and machine in the same sightline. In (A), the assistant, the scanner, and the patient are all facing the ultrasound screen ( arrows ). This is safest because the patient can be observed for any stress and decompensation while imaging. In (B) the head of the patient is away from the ultrasound screen. Both the assistant and scanner are focused on the screen and thus cannot readily appreciate any stress or decompensation of the patient, and cannot quickly react if the dog turns to bite them. The large "X" denotes that this is risky practice.

Source: Courtesy of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Figure 5.4. The helper hand and probe hand make a difference. In (A) the helper hand moves less haired skin and can help spread the hair for optimal probe head to skin coupling. In (B) and (C) the helper hand in essence V troughs the standing patient, preventing swaying and better stabilizing the probe for maneuvering in small increments, especially important for cardiac imaging.

Source: Courtesy of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Fan, Rock Cranially, and Return for AFAST Views

As a result of work by Boysen et al. in the original FAST translational study from humans to dogs, we have simplified and standardized the probe maneuver for AFAST as “fan, rock cranially, and return to your starting point” because 397/400 views matched for detecting free intraabdominal fluid when comparing longitudinal to transverse orientation (Boysen et al. 2004). And most abdominal organ anatomy during AFAST is easier to recognize in longitudinal and sagittal planes. Consider transverse orientation as an add‐on skill ( Figure 5.5).

Playing on the Short‐axis and Long‐axis TFAST Lines

In contrast to many echocardiography courses that begin with the long‐axis cardiac views, we begin TFAST with short‐axis views. Importantly, if the sonographer can grasp the “short‐axis line” and “long‐axis line” concept and fan the probe while staying on these lines, echocardiography views are learned more quickly and acquired more consistently by the noncardiologist sonographer ( Figure 5.6). Without even looking at the screen, knowing you are on these TFAST cardiac lines will optimize success. We could literally teach you from across the room, without any screen knowledge, by just seeing whether or not you are maintaining the ultrasound beam on these lines while fanning from the apex to the base on short‐axis, and from side to side on long‐axis using our clockface approach (see Figures 17.25 and 17.26).

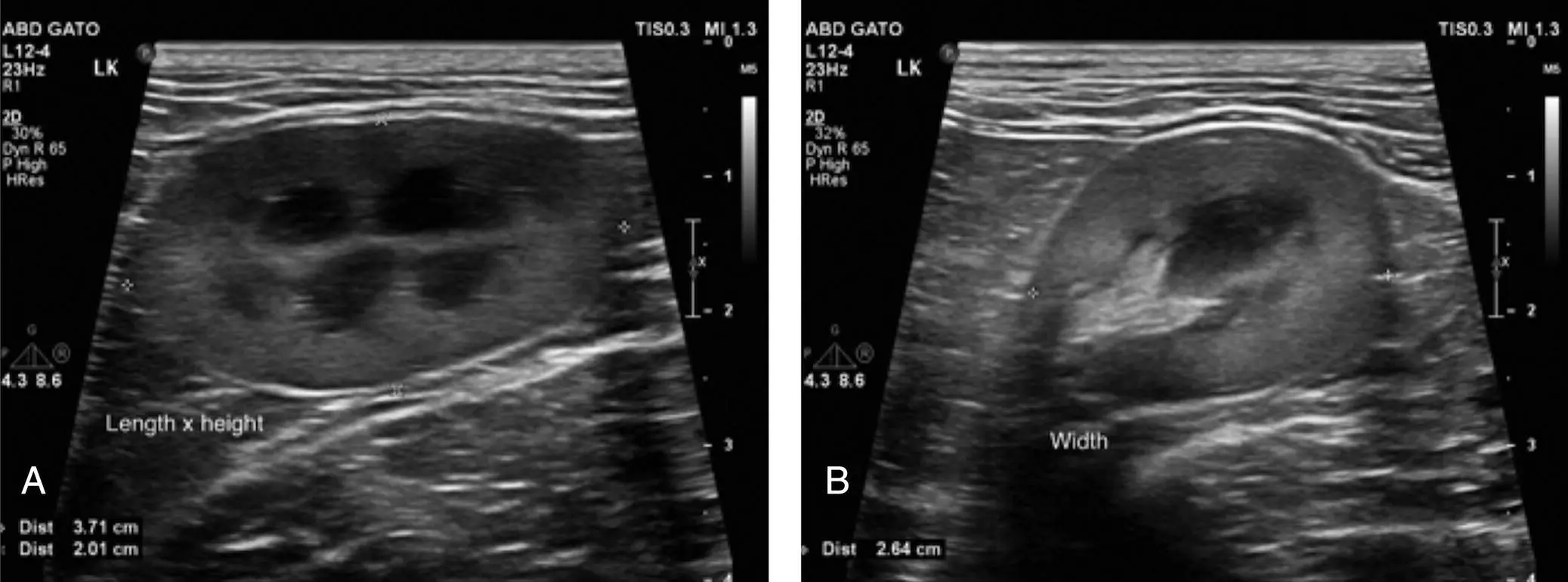

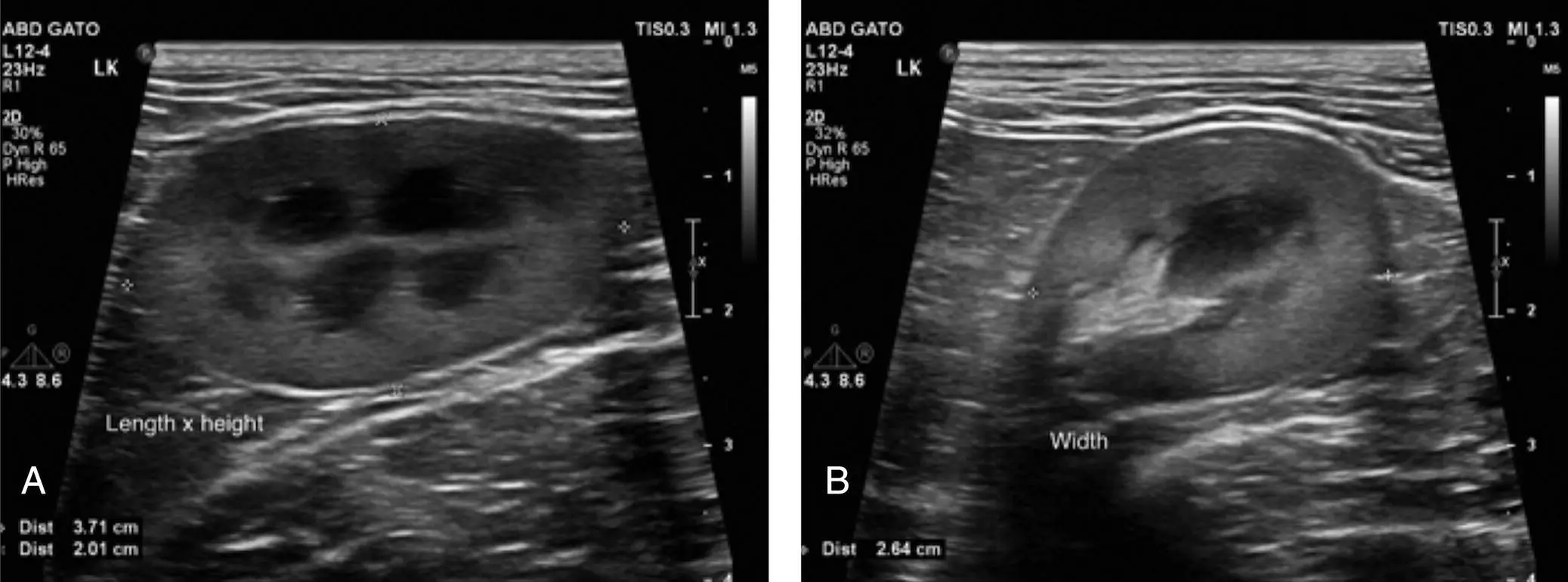

Figure 5.5. Anatomy generally better recognized in longitudinal (sagittal) orientation than transverse. In (A) the kidney is generally better recognized and then interrogated by fanning through longitudinal planes than in (B), showing the kidney in less recognizable transverse orientation.

Source: Courtesy of Dr Daniel Rodriguez, Mexico City, Mexico.

Figure 5.6. Short‐axis and long‐axis lines for echo views. If only someone had told me this back in 2005, to religiously keep the probe head parallel to the short‐axis (cardiac) and long‐axis (cardiac) lines while fanning, I would have gained proficiency so much faster. Trust these lines and fan while staying on them to achieve your echo views. We can tell from across the room whether or not you are successful by seeing if you are on these lines using a clockface orientation approach (Figures 17.25 and 17.26). Wander from them and everything gets goofy.

Source: Courtesy of Dr Gregory Lisciandro, Hill Country Veterinary Specialists and FASTVet.com, Spicewood, TX.

Failure to Maintain Probe–Skin Contact with the Patient

Every time you lose probe–skin contact with your patient, you delay the imaging and have to reestablish your acoustic window, losing precious time and potentially increasing risk in hemodynamically fragile (and stressed) patients. There are several recommendations that involve your nonprobe “helper hand,” placed into two broad categories: (1) maintaining probe–skin contact (acoustic window) by moving your patient's loose skin with the probe, and (2) maintaining probe–skin contact (acoustic window) by keeping your patient from swaying and at the same time stabilizing the probe against your patient's body.

We have found that the sonographer may take advantage of the patient's loose skin by moving the probe and skin together, and moving nearby less haired skin over the external landmark for your desired acoustic window. An example would be while doing Vet BLUE lung ultrasound, without losing probe–skin contact and your acoustic window, slide the probe together with the loose skin one intercostal space caudal and one intercostal space cranial when possible to cover the respective intercostal spaces at each respective Vet BLUE region. Another example is at the SR and HR views where the skin ventral to these views is often more sparsely haired, so your helper hand's thumb can lift or move this region dorsally over your external landmark of the costal arch and sublumbar muscles. By taking advantage of the sparsely haired area, imaging quality is markedly improved, especially in a thickly coated golden retriever, border collie or Siberian husky (see Figures 5.1and 5.4). Another AFAST location is the CC view. Placing the probe laterally but closer to the midline where there is obvious sparsely hair coated skin markedly improves the image.

Regarding maintaining probe–skin contact, we have some pearls. First, when your patient is standing during the Global FAST approach, use your helper hand to “V trough” the patient by holding both sides of the sternum ( Figure 5.7). This is especially helpful for evaluating your TFAST pericardial site (PCS) views but may also be used during Vet BLUE. Second, use your helper hand to brace your probe against the thorax or abdomen for better control of fine probe maneuvers.

Читать дальше