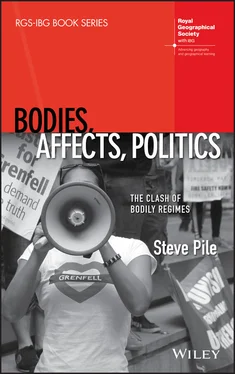

As importantly, there is a shared struggle not only to voice the injustice, but to have their voices heard and recognised. Those voices are heard in moments. All too often, justice is undermined by a logic of blame: the claim for justice – formed around a much wider experience of inequality and injury – reduced to a demand for someone to be held responsible. Just as the police had sought to blame the victims, Liverpool fans, for their own deaths at Hillsborough, so the finger of blame has begun to be pointed at the firefighters for their supposed failure to evacuate people from the burning tower.

The parallels in the aftermath of the tragedies also lie in the difficulty of making anger, truth and justice stick together, especially over long periods of time. The parallel lies in the ease with which political institutions can detach heart‐break from anger, anger from the demand for justice, and justice from the political will to change public institutions, such as the police (Hillsborough) or the council (Grenfell): for example, by circumscribing the terms of reference of inquiries. Facts and affects are cauterised from one another: justice de‐politicised by its gradual assimilation into the legal process. Thus, broader questions about what justice looks like – which are as political as it gets – are transmuted into narrow socio‐technical questions, about cladding, about cost efficiency, about sprinkler systems. These are, of course, important issues, but this transmutation effectively converts the politics of social change into a politics of small changes.

What replaces justice is, as we have seen, heart‐breaking. Yet, the over‐riding heart‐break of the tragedy can itself shape how we understand what went before. It can be easy only to see the tragedies that led up to the tragedy, making the tragedy appear inevitable, the only possible outcome of all the injuries and inequities that went before. Yet, Grenfell Tower, as a microcosm of London life, has more than one story to tell.

For most news outlets, including the BBC, and the Inquiry itself, the single most important story about Grenfell is the story of the fire and its victims: its causes, its shockingly quick spread up and around the tower, the horror of the escape…and tragic, heart‐breaking, unbearable death. Yet, out of this story emerges another story: the story of a tower that was teeming with life, giving us a glimpse of a different kind of London – not broken, but getting along. To show this, let’s turn to the BBC’s remarkable reconstruction of the twenty‐first floor (which was chosen by the BBC because it was emblematic of the fine line between life and death) for a Newsnight special, put together by Katie Razzall, Sara Moralioglu and Nick Menzies, broadcast on 27 September 2017 (see www.youtube.com/watch?v=‐cY_fgeeCzc). The report contains interviews with residents, talking about their beautiful homes. A BBC News webpage recounts the story:

Two IT workers. A civil engineer. A hospital porter. A charity worker. A management consultant. A supervisor in a clothes shop. A market stall employee and part‐time student. A beauty salon owner. A retired waitress. Ten adults and five children lived on the 21st floor of the Grenfell Tower. Nine of them survived the fire. Six of them – and one unborn baby – perished. ( www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt‐sh/Grenfell_21st_floor. Last accessed July 2020)

As Rajiv Menon observed at the inquiry, the story of Grenfell was wrapped up in histories of class, race and social inequality (see also Shildrick 2018). After the fire, these grand narratives were replaced with ordinary stories about family, home, work and living alongside different people. Like all other floors (above the fourth floor), the twenty‐first floor was organised into four two‐bedroom flats and two one‐bedroom flats. The two‐bedroom flats each had a corner of the tower, with the one‐bedroom flats sandwiched between them. All had access to a central lobby, with lifts and a single stairwell. The Gomes family – Marcio and Andreia and their two primary school‐aged daughters, Luana and Megan – lived in Flat 183. Like many residents, they enjoyed living in the tower. The flats had big rooms for the family, but the kids would also play in the tower’s communal spaces. Marcio and Andreia are first generation migrants from Portugal. They had lived in the tower for 10 years, but still considered themselves ‘newcomers’, as many of their friends had been in the tower more than 20 years. Marcio works in IT, while Andreia is a supervisor in a clothes shop. In the tower, Marcio observes:

The diversity was great, you’d meet all sorts of different people – Irish, English, Arabic, Muslim, Portuguese, Spanish, Italians. You’d get to see different cultures. You’d go up in the lift with lots of different people; you’d talk; the kids would play. The tower itself was a community; it was very family oriented. It’s been portrayed as a poor tower, a broken tower. It was far from that.

The Gomes family escaped because they were woken by Helen Gebremeskel and her 12‐year‐old daughter Lulya, who lived in Flat 186, a two‐bedroom flat diagonally opposite Flat 183. Helen Gebremeskel was born in Eritrea and arrived in the United Kingdom as an asylum seeker when she was a child. She had been living in the tower for 20 years, but only moved into Flat 183 in 2014. She had spent the last few years renovating and decorating her new home. Helen Gebremeskel is the managing director of, and hairstylist at, H&G International Hair and Beauty Salon. Lulya’s best friends were the Choucair family, which lived on the twenty‐second floor. On the night of the fire, they had called Bassem Choucair to tell them to get out. The Choucair family did not get out; all died in the fire.

Helen Gebremeskel decided no one was coming to help, so made the decision to leave, against the advice of the emergency services (following accepted procedure). By the time she and Lulya went to the Gomes’ flat, the fire had already been burning for over half an hour. Thick black smoke forced them all back into the Gomes’ flat. For two hours, they attempted to keep the smoke out: they opened the windows, ran the bath and shower water. At around 3.30 a.m., the Gomes bedroom caught fire. The six of them wrapped themselves in wet tea towels and sheets to make their escape. Although they made it down through the horror of the stairwell, Lulya, Luana, Megan and Andreia were put into induced comas and treated for cyanide poisoning. This is when (as we heard above) Andreia’s baby boy, Logan, was stillborn.

In Flat 182 lived the El Wahabi family, which had turned their flat into what neighbours described as a ‘mini Morocco’. The father, Abdulaziz, worked as a porter at University College Hospital, while his wife, Faouzia, worked for the Westway Trust, which seeks to utilise the space underneath the Westway flyover for community benefit. They lived with their three children: Yasin, a part‐time accountancy student at Greenwich University; Nur Huda, who had just completed her GCSE exams and loved football; and Mehdi, who attended a local primary school and enjoyed judo. Helen Gebremeskel had seen the family escaping at around 1.30 a.m., but then the family had opted to return to their flat. They called the emergency services, which told them to stay in the flat. All five died in the fire. Abdulaziz’s sister, Hanan, and her family lived in Flat 66 on the ninth Floor, but they all made it out.

On the twenty‐first floor, there were two one‐bedroom flats. According to Razzall, Moralioglu and Menzies, the occupancy of Flat 184 was uncertain. They reported rumours about a woman from the Philippines, illegally in Britain, living there. It later emerged that the flat was occupied by Mustafa‐Sirag Abdu (see news.channel4.com/2017/grenfell‐tower/). He is a civil engineer from Ethiopia. He left the moment he heard about the fire. Ligaya Moore, a 78‐year‐old grandmother, lived in Flat 181. She had lived alone since the death of her husband, Jim, several years ago. She had moved to London from the Philippines in 1972 and had worked as a nanny and a waitress. No one saw her that night. It only adds to the tragedy that her absence became the stuff of rumour; rumour with a racist tinge.

Читать дальше