In contrast, the Justice4Grenfell campaign, along with the Fire Brigade’s Union, organised a more conventional protest march on the Saturday, 16 June 2018, immediately following the silent walk that marked the first anniversary of the tragedy. Assembling outside Downing Street (residence of the British Prime Minister), the march began with speeches decrying the council, the government and the contractors who installed the cladding on the tower. More importantly, the speakers each affirmed the need to look back over the longer history of the tower. They talked about how the tower had been built to high standards, yet had been left to decline through decades of under‐investment under successive political regimes. They vented fury at austerity urbanism that the Tory‐led council had embraced with enthusiasm – focusing its attention on profits, rather than living standards and safety. The silence was powerful, the speakers affirmed, but they wanted this protest to be noisy. From Downing Street, the march wound its way past the Houses of Parliament. The Houses of Parliament are currently undergoing a £3.5~7Bn refurbishment, ironically, partly prompted by fears that the risk of fire is so great that the building is a death trap (reported by The Guardian , 31 January 2018).

At the Home Office, the government department responsible for overseeing the conduct of councils, the march paused. Here, speakers condemned the government’s politics of race, which casts migrants as a problem and as unwelcome in the United Kingdom. Speakers pointed to the Muslim community that had been the first to respond to the fire, running towards the fire while the politicians ran away from it. The politics of justice, in this form, pits itself not just against the injustices perpetrated by Conservative Governments, but against the politics of government in general, Labour and Conservative, that have failed ‘the community’. As the marchers left, they chanted: ‘Tell me what community looks like/This is what community looks like’ ( Figure 1.1).

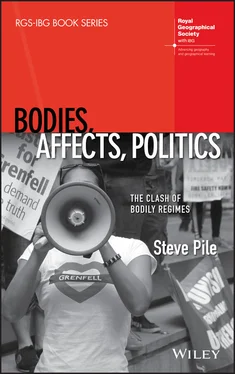

Figure 1.1 The Justice for Grenfell March to mark the first anniversary of the Grenfell Tower fire, 16 June 2018, as it passed the Houses of Parliament a second time (on the way back from the Home Office).

Source: Steve Pile.

The speakers on the march drew clear parallels between the anti‐migrant discourse of Brexit (on both the remain and leave sides), the scandal of the Windrush generation (who had become collateral damage in Theresa May’s 2012 creation of ‘a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants’ in the United Kingdom, but especially from early 2018 onwards) and the systemic underinvestment and marginalisation of the Grenfell community (see Bradley 2019; and, El‐Enany 2019). So, when the march asked what community looked like, it was not simply making visible an affective community forged by compassion, grief and anger, it was pointing out that the body of the community was forged out of racial and religious diversity. This community incorporates invisible and visible differences.

The Grenfell Tower tragedy altered a pervasive narrative about Muslims and community in London that had become dominated by suspicion and fear. For example, in the wake of multiple terrorist attacks – an attack at London Bridge by three Muslim men less than two weeks before the Grenfell Tower fire had killed eight people – Muslim communities were constantly being asked to account for their relationship to Islam. The Grenfell Tower tragedy uncouples the relationship between Islam and terror in two significant ways. On the one hand, the stories of the survivors are about the lives of ordinary Londoners: making their homes beautiful, working hard, getting on, looking after family, and living in a community of friends and strangers. This ordinariness undoes a divide between Muslims and everyone else. This is evident in the ‘wall of truth’, which does not discriminate between faiths and backgrounds (see www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt‐sh/grenfell_tower_wall). On the other hand, Muslims were prominent in organising and providing support. The Al Manaar Muslim Cultural Heritage Centre is now a symbol for Islamic generosity, aid, support, community. Consequently, when Muslim Aid produced a report in May 2018 praising the voluntary sector for its response to the fire, while also being critical of the council response, it was widely reported by national news media (see, e.g., www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk‐england‐london‐44295397).

In the wake of the Grenfell fire, we can see that the normal conventions through which local people are rendered visible and invisible, heard and unheard – and, the common frames through which their bodies and lives are understood and interpreted – were, however temporarily, suspended. Instead, unheard stories were told and listened to: stories about migration, race, class, family that all challenged received understandings about tower block life and the composition of community. In part, the shock to the system turns around the event itself and the affective intensity of the moment. Yet, we can also see the ways that affects enabled the crystallisation of an operable community, forged around a shared sense of injustice and a demand for justice. It is therefore worth noting that one of the first marches in London, on Sunday 31 May 2020, to protest the death of George Floyd (in Minneapolis) ended at Grenfell Tower. In silence. As someone wrote Black Lives Matter on the memorial wall.

Before the fire, there were long histories of class, race and social inequality that were all refracted through notions of violence and poverty. Grenfell exposes these: its anger is intimately connected to them. Yet, it also exposed the ordinary affects of family, work, humour, hope, childhood and so on (see Highmore 2011; and Stewart 2007). Communal solidarity formed around the tragedy, not only through anger and feelings of sorrow and generosity, but also around these ordinary affects. This underscores Rancière’s injunction to see politics as a form of experience, not in its exceptionality, but in its everydayness. This asks us to pay particular attention to ordinary life in Grenfell Tower, as a political moment that invites us to consider how people are assigned to places and to a place in life.

Following Rancière, we can see the emergent stories and voices from Grenfell Tower as a challenge to the distribution of the sensible (2004, p. 8; see Dikeç 2015): that is, a recasting of common sense understandings of race, class and religion. In Rancière’s terms, this recasting was forced by marginalised and excluded bodies challenging accepted ways of understanding those bodies, as if from the outside of a bodily regime (to use Fanon’s expression) that seeks to define bodies and assign them a proper place in the scheme of things. In these terms, a bodily regime defines, and is defined by, the senses: not just the visible and the invisible, but all the ways that things are sensed or not, understood or not. Bodily regimes are about how the senses are defined and lived. Significantly, bodily regimes are produced and reproduced by the drawing of an epistemic boundary that differentiates between the sensible and the insensible. This boundary enables a distinction between people who are inside a community of shared sensibilities and those who are outside:

The distribution of the sensible reveals who can have a share in what is common to the community based on what they do and on the time and space this activity is performed. Having a particular ‘occupation’ [both an activity and a space] thereby determines the ability or inability to take charge of what is common to the community; it defines what is visible or not in a common space, endowed with a common language, etc. (2004, p. 8)

Читать дальше