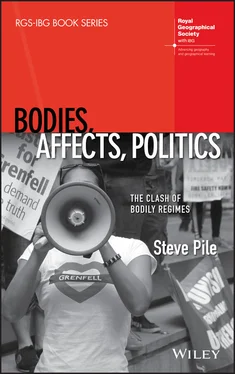

As Mario Cacciottolo wandered around the streets surrounding Grenfell Tower, he discovered another story. He spoke with Christina Simmons, who had lived near the tower for 27 years. She explained: ‘People are coming together and rallying together. I didn’t realise we had so many Eritreans and Somalians; they’ve come out to offer support’. The growing pride in the community response did not mask the problem. Christina added, ‘They don’t listen to us. We’re being neglected and ignored. I’m bloody angry’. Then, on a more hopeful note, ‘Maybe this’ll bring us all together’.

A day later, the relief effort of the council had not improved. The communal effort, meanwhile, was now enormous, with makeshift relief centres at the Westway Sports Centre and St Clement’s Church straining under the weight of goodwill. While the Queen and Prince William calmly met volunteers, local residents and community representatives at the Westway Sports Centre, a large angry crowd gathered outside St Clement’s Church, where Theresa May was due to meet victims of the disaster. As she appeared, clear on the TV reports were shouts of ‘coward’ and ‘shame on you’. Some broke through the police cordon to shout at the Prime Minister as her car whisked her away. It is not clear whether Theresa May heard them.

The fire at Grenfell Tower exposed the growing social inequality in the area and tensions around gentrification as well as the indifference and unpreparedness of the local council and the Conservative Government (although they would protest otherwise). Yet, the fire also changed the way the area was seen and heard. Perhaps the most remarkable shift was prompted by the communal response: the tragedy operationalised a community that was previously latent and fragmented. Indeed, the escalating acts of compassion crystallised what appeared from the outside to be an impossible community. Significantly, community was quietly articulated through faith‐based organisations – especially St Clement’s Church and the Al Manaar Muslim heritage centre – and expressed (informally) in religious terms (see, e.g., Everett 2018).

On a wall of the Latymer Community Church, in an echo of other tragedies in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, people wrote tributes and messages, and left flowers (see www.getwestlondon.co.uk/news/west‐london‐news/gallery/tribute‐wall‐grenfell‐tower‐community‐13191587; and, www.standard.co.uk/news/london/hundreds‐of‐harrowing‐messages‐left‐on‐wall‐at‐grenfell‐tower‐fire‐scene‐a3565521.html). At the centre of one panel, underneath a wicker heart, in multicoloured felt pen, were the words: ‘Pray for our Community’. Surrounding these words were messages of love, grief and hope, written in English and Arabic. Many of the messages were drawn upon religious themes, practices and iconography to articulate a sense of community: ‘No words can truly describe the pain, the fear, the sense of being lost – only emotions to be felt – the heart felt prayers of the whole world are here and with time and peace will heal and reunite loved ones’. Another read: ‘What a wonderful response to a horrible tragedy. May we continue to give so that no one is in lack. This is the kingdom of Jesus Christ’. Alongside it, someone had written: ‘May Allah grant all the highest ranks in jannah, and all the survivors the strength to carry on’. It wasn’t just that the fire had revealed the different faiths in the community, it was that the commonalities amongst the seemingly incommensurable faiths had become the grounds upon which people were acting together. Theologically different ideas about the soul and heaven found common ground in the articulation of a desire that people’s souls would find heaven and rest in peace. Gifts and giving were at the heart of a now operative impossible community, underpinned by expressions of love, hope, help, resilience, sympathy and strength.

The operability of community was often expressed through ideas of togetherness and unity: ‘Bonds formed in fire are difficult to break – our community will always stand together’. And, on another panel, simply: ‘WEARE1’. On the other hand, community was also what set people apart from the rich and the powerful: ‘May their souls rest in peace #PPPpoorpeoplepolitics’, ‘People help the people’. And, there was also a palpable sense of anger and a desire to see justice: ‘Why did this need to happen?’, ‘Theresa May where are you, your people voted you in, Justice for Grenfell, Jail Those Responsible’.

The operative community quickly was becoming two‐sided: one side, joining the people together, while at the same time separating the people from the rich and the powerful. The demand for justice similarly faces in two opposite directions at once. One demand is faced towards the law. This is the demand for the causes of the tragedy to be identified and the people responsible to be held accountable: this is what Rajiv Menon calls ‘real justice’ and ‘real accountability’ (see above). Theresa May’s quick declaration that there would be a public inquiry addresses this demand: yet, the public inquiry also utilises the limits contained in this demand for justice – the inquiry’s remit would not extend to wider questions of race, class and social inequality. Yet, that circumscription of the inquiry itself creates a contestable limit. Another demand faces away from the law as the law itself is the source of injustice. This demand for justice chains the tragedy to longer histories of racism, social inequality and deprivation. It is glued to a sense of injustice that calls into question the meaning of justice. In this, Hillsborough is a marker of what justice does not look like. It does not look like the legal process and the rule of law. It does not mean years of struggle against ‘the system’ by heart‐broken, nearly exhausted, resource poor, working families. It does mean taking into account – and redressing – long histories of class, race and wider social inequalities (as Gordon Macleod, Stuart Hodkinson and Ida Danewid, amongst many others, argue).

Tell Me What Community Looks Like

In his analysis of a fire at the Imperial Foods plant on 3 September 1991 in Hamlet, North Carolina, David Harvey observes:

We here encounter a situation with respect to discourses about social justice which closely matches the political paralysis exhibited in the failure to respond to the North Carolina fire. Politics and discourses both seem to have become so mutually fragmented that response is inhibited. The upshot appears to be a double injustice: not only do men and women, whites and African‐Americans die in a preventable event, but we are simultaneously deprived of any normative principles of justice whatsoever by which to condemn or indict the responsible parties. (1993, p. 53)

The parallel between the Imperial Foods fire and the Grenfell Tower fire is uncanny. Yet, it is also misleading. In fact, the inquiry – which is capable of identifying those responsible (as with the Hillsborough inquiry) and making recommendations for changes (such as, most likely, new fire regulations regarding cladding materials) – focuses the political response on technical matters: thus, ‘real justice’ and ‘real accountability’ are exactly what can be delivered, while looser, more unruly, notions of justice become marginalised and silenced: literally, as Moore‐Brick’s rebuke of the audience at the inquiry demonstrates (see above).

Brilliantly, the community has turned these silencing strategies on their head. Silence has become a means through which to remember the tragedy, to reconfirm a commitment to remember what happened and to struggle for justice (see Charles 2019). On the fourteenth of every month, since the fire, there has been a ‘silent walk’ to pay respects to those who died. It starts at Notting Hill Methodist Church and follows a path towards the Lancaster West Estate. On the first anniversary of the fire, not only was there a nationwide minute’s silence in the morning, there was also a silent procession at noon to the ‘wall of truth’ at the Maxilla Social Club, followed by an afternoon silent procession to the Methodist Church, ending with an evening silent walk starting at the wall of truth. The silent walks are more than an act of remembrance, however. They express the solidarity of the community; they also symbolise the way that community voices continue to be ignored (see www.grenfellconnect.org.uk). Significantly, after the walks, there were also prayers and remembrance at the Al Manaar Muslim Cultural Heritage Centre.

Читать дальше