Flat 185 had been bought from the Council under the right‐to‐buy scheme in 2000 by the tenant Nigerian‐born Tunde Awoderu. A few years later, Awoderu moved out, and the flat became private rented accommodation. He was now vice‐chair of the Grenfell Leaseholders’ Association. Flat 185 was one of 12 privately owned flats in the tower. Eleven days before the fire, Stewart Lee, a 29‐year‐old IT engineer, and boyfriend Julian Ng, a 30‐year‐old management consultant, moved into Flat 185, paying the over £1700 a month rent between them. Both Stewart and Julian were born in Britain. On that night, Julian was working in Crawley. It was Stewart’s birthday, so he decided to take the day off and to stay with Julian at his hotel. At 3 a.m., Tunde called them, very concerned about their safety. In shock, they watched the tragedy unfold on their smartphones (as reported in the Pink News , 14 June 2017).

These are stories about previously unheard voices, speaking in unfamiliar ways. Tower blocks are overwhelmed stories of poor housing, unemployment and social deprivation. Indeed, as Ida Danewid has shown, placed in an international context, Grenfell can be seen as a consequence of wider forces of racial capitalism that is reconfiguring colonial and postcolonial relationships within London (2019). From this perspective, Grenfell is more than just ‘Empire coming home’, it is about the way racial capitalism is shifting people and capital around the world, involving a racist global necropolitics in which the lives of black people do not matter. Indeed, the relationships within the tower were diverse, geographically; they stretched to places far away, to Morocco and to Ethiopia, to Italy and to the Philippines. Yet, Grenfell also domesticated the global: showing how migrants had settled in London, revealing migration to be homely and familiar, ordinary ( www.bbc.co.uk/news/world‐44395591). The testimonies of those living on the twenty‐third floor, whether they intended to or not, made it clear that these homes were beautiful, the people in the blocks were hard‐working, and they had created bonds of friendship and community. Evidently, too, this was not true for everyone: some people were isolated, not able to turn to friends, their families far away. Grenfell holds more than one story, at the same time.

People had settled into London life, working nearby, going to school, moving within the tower and within the neighbourhood. The tower block was diverse, socially: alongside young urban professionals were public sector employees and charity workers. A system of ‘self‐evident facts’ (as Rancière puts it, 2004, p. 7) about tower blocks was being systematically shaken: the block’s many jarring stories were demanding to be heard. In Rancière’s terms, this amounted to a challenge to the distribution of the sensible: that is, a regime of perception and understanding through which people, ideas and things are assigned a ‘proper place’ in relation to other people, ideas and things. In particular, dominant narratives of class and race – intimately connected to notions of social housing, refugees, migrants and tower blocks – were being directly challenged. Not just through stories about community and hard work, but affectually through stories of love, family, hope and unassimilable trauma and grief (see also Doherty 2018).

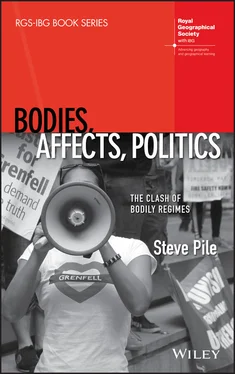

Following Rancière (2000), we can also argue that, in the aftermath of the fire, bodies were torn from their assigned places and a form of free speech and expression emerged. For a few days, these bodies caused a disruption in the ordering of relations of power, not by revolution or riot, but by affect: that is, affect was having political effects (following Massumi 2002, p. 40). The hurt and pain and loss and anger simply overwhelmed the political response, with its focus on emergency services, its desire to convert the fire into a set of technical questions of fire‐proof properties of cladding and architectural design, and into amounts of money (£5 million, up front). These affects cut across forms of cultural and religious identity, altering questions of belonging and hierarchy: the Grenfell Tower fire brought new subjects into the field of perception. Working class, migrant and refugee, and community voices were being expressed, heard and spread. Grenfell, then, is a story about voices lost – and voices gained. More, perhaps most importantly, the story of the tower is also a struggle over what justice looks like.

Grenfell’s stories of loss, pain and grief are exacerbated by another story: the failure of the council and government to respond adequately to the tragedy, both in the days after and the following months, with survivors still living in temporary, unsuitable accommodation. In this story of Grenfell, venal political indifference is pitted against the strength of the community (see Madden 2017).

As people were being taken to hospitals across London, as the fire was still burning, and as the council failed to comprehend or respond to the scale of the tragedy, people from the surrounding area were already starting to donate food, water, bottles, blankets, clothing, nappies, toys at St Clement’s Church, the Al Manaar Muslim cultural heritage centre, the Notting Hill Methodist Church and the Westway Sports Centre as well as Kensington Town Hall. As the council floundered in its response, the communal response was immediate…and it was as compassionate as it was angry. These were the resources out of which a strong community emerged. Politicians were keen, too, to show how much they cared.

Leaders of both the major political parties visited the Grenfell Tower scene on the morning of 15 June. At 10 a.m., Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May made what was called a ‘private visit’, meeting members of the emergency services. A couple of hours later, Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the Labour opposition, arrived at the scene. The contrast between the two visits could not have been starker, and people were quick to point this out on social media. On BBCTV news, images of Jeremy Corbyn listening to local people voice their anger and putting his arm around a distressed woman inside St Clement’s Church were juxtaposed with Theresa May’s seemingly dispassionate conversations with groups of firefighters and police. People were quick to criticise Theresa May for not meeting residents, for not being prepared to take their anger and pain. More, she was condemned for talking to people via TV about how the government would do everything it could to help and rehouse them. She was being condemned as much for not listening as for not talking; as much for failing to be open to people’s anger and pain as for a seemingly dispassionate display of compassion. Perhaps in an attempt to seem more human and humane, just before 2 p.m., Theresa May announced that there would be a full public inquiry. During the morning, the official death toll figures had risen from 12 to 17. No one thought the death toll would stay at 17; many thought it would rise into the hundreds. The sense that officials were underestimating the tragedy only intensified the anger on the streets around Grenfell Tower.

While Theresa May was announcing the public inquiry, freelance journalist Mario Cacciottolo, writing for the BBC, was reporting the views of local residents ( http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk‐40291372). He spoke to Maria Vigo, who had lived opposite the tower for 11 years. She told him: ‘There was a lot of anger on the school run this morning. There’s a lot of separation between the classes, and people are telling me that it’s down to social cleansing’. She complained about being priced out of the area by the rising cost of basic amenities. She blamed gentrification. ‘This area’s always been working class. It’s starting to become a bit less so now, and the working class are feeling that they’re being left without a voice. The council isn’t listening to us. We don’t want a pretty building. They should ask us ‘what do we need’? Or ‘what would we like’? In the rich borough of Kensington and Chelsea, Grenfell Tower stood in an area (surrounding the Latimer Road tube station) that ranks amongst the poorest 10% in England.

Читать дальше