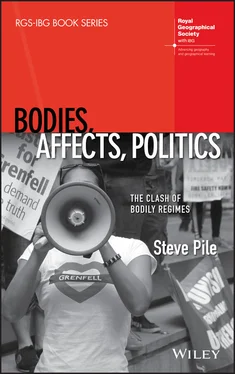

The change in the headline might, on the surface, seem innocuous for both are highly emotional: one headline speaks to the families’ angry demand for justice, while the other picks up on the families’ unbearable loss. These two stories have the same source – yet, in this moment, the unrelenting anger that inhabits the demand for justice is replaced by the unspeakable grief and horror of the tragedy. Perhaps, maybe, because a story about the tragic loss of a child would have more appeal for the Evening Standard (a free paper that relies on advertising revenue) than the demand for justice. Yet, although the headlines both draw on Marcio’s words, the switch in headlines represents the first signs of the separation of different strands of the Grenfell story: with the raw emotion of unbearable loss becoming detached from the rage‐filled demand for justice.

That said, in this moment, anger and grief and hope and love and justice and truth are not yet cauterised from one another. Listen to Emanuela Disaro, mother of Gloria Trevisan, a young Italian architect who was trapped on the twenty‐third floor by flames coming up the single stairwell. In a phone call on the night of the fire, Gloria had told her mother, ‘I am so sorry I can never hug you again. I had my whole life ahead of me. It’s not fair’. Speaking through a translator, Emanuela told the inquiry on 29 May 2018 that she had taught her children not to hate, but that she felt a lot of anger: ‘I hope this anger is going to be a positive anger. I would like this anger to help to find out the truth of what happened’. A positive anger would, Emanuela hoped, lead to justice.

Anger, Truth, Justice. Intimately connected. Yet the Evening Standard ’s West End Final edition headline suggested that this might not be enough: bound up in the demand for justice was the feeling that justice should also mean not having to fight for justice. Maria ‘Pily’ Burton, wife of Nicholas, was the seventy‐second victim of the fire: although rescued by firefighters from the nineteenth floor, she eventually died in January 2018 after months of medical care. Nicholas voiced the concerns of many of the bereaved. He told the Standard : ‘We should not have to fight so hard to be heard, but every step of the way so far has been a battle. You look at the Hillsborough families, still suffering after almost 30 years. We have to make sure we don’t have to wait 30 years for justice’ ( Evening Standard , 21 May 2018 West End Final, p. 4; West End Final Extra, p. 5). The demand for justice and truth may be embedded in and motivated by anger, grief and suffering, but it also reaches out to feelings of sympathy, generosity and urgency. Or, their lack.

Nicholas Burton’s reference to the Hillsborough families is highly significant. Hillsborough refers to the deaths of 96 Liverpool fans, crushed to death on the Leppings Lane terraces of Sheffield Wednesday Football Club on 15 April 1989. In fact, if justice is the punishment of those held to be responsible, the Hillsborough families will never see it. Criminal trials associated with the disaster only began on 14 January 2019. Indeed, as a forewarning for those seeking justice for Grenfell Tower, the original intention to prosecute six people, including four senior police officers (including the chief constable), weakened. In the end, only two of the six faced trial: David Duckenfield, the police officer in command on the day, and Graham Mackrell, former Sheffield Wednesday club secretary and safety officer; charges including gross negligence manslaughter (Duckenfield) and breaches of safety regulations (Mackrell). The outcome of the trial, on 3 April 2019, was under a fortnight short of the thirtieth anniversary of the tragedy. While Graham Mackrell was found guilty of a single health and safety charge, and later fined £6,500 (with £5,000 costs), the jury could not agree a verdict for David Duckenfield. At his retrial in November 2019, after over 13 hours of discussion, the jury eventually found Duckenfield not guilty. Afterwards, the Hillsborough families asked a simple question: given that the 96 people killed at Hillsborough were found to have been unlawfully killed, who will be held to account? No one will ever be convicted of their deaths.

In the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell fire, the families and survivors were already acutely aware of the struggle for justice in the wake of the Hillsborough disaster. Indeed, groups from both tragedies would meet each other and share some of the same lawyers. In many ways, theirs is a shared struggle over truths: not just over what happened and whose testimony counts, but also over how these truths are to be interpreted and contextualised.

After completing the commemorative hearings, on 4 June 2018, the Grenfell inquiry began to hear evidence about the events that led to the tragedy. The fire had begun when a Hotpoint fridge‐freezer had caught fire in Flat 16, Floor 4, where Behailu Kebede lived. It was Kebede who had first called the emergency services, asking them to come ‘quick, quick, quick’. Representing him was a lawyer who had also represented families at the Hillsborough inquiry, Rajiv Menon QC. Towards the end of a prepared statement, Rajiv Menon rounded upon the remit of the inquiry. He noted that the judge, Sir Martin Mason‐Brick, was unlikely to reverse his earlier decision and take the wider context into account. However, Menon was not to be deterred. It is worth hearing him at length (video is available at www.youtube.com/channel/UCMxYjfZsqLa8DanN0r2eNJw. Extract from minute 30:30 to 35:51):

There are certain stark irrefutable facts that one cannot simply ignore about the underlying social, economic and political reality and conditions that culminated in 71 people dying from smoke and fire in a high rise residential building, and a seventy‐second person dying a few months later, in one of the richest boroughs in one of the world’s great cities in one of the richest countries in the twenty‐first century. It is no coincidence that this fire occurred in a building consisting of social housing and former social housing purchased under the right to buy scheme and not in one of the posh swanky high‐rise residential buildings around London that cater to the extremely wealthy. It is no coincidence that this fire occurred in a building owned by a Tory flagship borough that has been at the forefront of promoting austerity cuts and deregulation and promoting business and profit over health and safety….

Off camera, someone in the audience shouts ‘Justice for Grenfell’; others clap in support. The presiding judge, Sir Martin Moore‐Brick, turns to the audience and solemnly insists that there will be no (further) interruptions of proceedings. Menon continues:

… It is no coincidence that the vast majority of the residents of Grenfell Tower were first or second‐generation migrants and refugees, the remaining residents being largely local people with long‐standing roots in the north Kensington area. Amongst the 72 that died, 23 countries and more were represented. So, race and class are at the heart of the Grenfell story whether we like it or not, whether the inquiry acknowledges it or not, whether the terms of reference are extended or not. Consequently, we say that what happened at the Grenfell Tower in the early hours of June last year was as political as it gets and symbolic of a deep inequality in our society.

The parallels between the Grenfell Tower and Hillsborough tragedies are not connected to the high number of victims, nor to the length of time that public inquiries take, nor to the uncertain possibility that anyone will ultimately face what Menon calls ‘real justice’ and ‘real accountability’. The parallels lie in deep and persistent inequalities in society, especially around class. Indeed, for writers such as Gordon Macleod (2018) and Stuart Hodkinson (2019), the core of this inequality is to be understood in the context of a systematic neoliberal assault on the welfare state, which has rendered public housing marginal, neglected, devalued and stigmatised. They point to the way that the local council, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, ignored regular complaints by the residents of Grenfell Tower about its safety, including the lack of a sprinkler system. To this is added the actions of an austerity‐driven ruling Conservative Party and unscrupulous private contractors. This view positions Grenfell in a long history of neoliberal assaults on the working class, especially on conditions of work and housing, since Thatcherism in the 1980s (see de Noronha 2019; and also Radical Housing Network, Hudson and Tucker 2019). Indeed, Hillsborough is easily seen as part of this assault.

Читать дальше