The coronavirus will teach us many things. Like as not, virology aside, it will mostly teach us what we already know. And I am no different. The coronavirus teaches me that we live in a precarious world, made scary and infuriating by the (extra)ordinary politics of the body and of bodies (from facemasks to lockdowns). But, the world was already fractious and precarious, people already living everyday with crisis after crisis (from floods to droughts, species extinction to financial collapse, from sexual abuse to police brutality), living with deep anxiety and apprehension alongside the propensity for great kindness and generosity. And, I guess, in some small way, this book is a response to the already existing and long‐standing ‘unsettlingness’ of modern life, an ordinary indeterminacy that runs through bodies, through affects and through politics.

This book has been in process for a long time, longer even than the torturous process of writing. There are three things to say about this. First, it is normal to thank specific people when writing academic works. Part of the argument of this book is that it is never that clear where ideas (or feelings) come from. So, I want to thank everyone I have talked to about the matters contained in this book. You have all made some difference to what is here. I admit, in ways that I am probably unaware, and more profoundly I am sure than I know. So, thank you. Second, to contradict myself, I need to thank three people without whom this book would not appear in the world: David Featherstone, whose insights have been incalculable; Jacqueline Scott, whose patience I have sorely tested; and Nadia Bartolini, who has had to endure far too much. Third, I need to acknowledge the source material for certain chapters. Chapter 2reworks ‘Skin, Race and Space: The Clash of Bodily Schemas’ in Frantz Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks and Nella Larsen’s Passing , which was published in Cultural Geographies in 2011 (pp. 25–41). Chapter 3draws on ‘Spatialities of Skin: The Chafing of Skin, Ego and Second Skins’ in T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom , which was published in Body & Society , also in 2011 (pp. 57–81). Chapter 4recasts ‘Beastly Minds: A Topological Twist in the Rethinking of the Human in Nonhuman Geographies Using Two of Freud’s Case Studies’ by Emmy von N. and the Wolfman, which was published in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers in 2014 (pp. 224–236). Chapter 5adds a case study of Dora, drawing on a sole authored first draft for the introduction that Paul Kingsbury and I wrote for Psychoanalytic Geographies (2016, pp. 8–15) to my chapter in that book, ‘A Distributed Unconscious: The Hangover, What Happens in Vegas and Whether It Stays There or Not’ (pp. 135–148). Similarly, Chapter 6removes substantial material from ‘Distant Feelings: Telepathy and the Problem of Affect Transfer over Distance’, as published in Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers (2012, pp. 44–59) so as to add material from the case study of Dora, drawing on a sole authored first draft for the introduction Paul Kingsbury and I wrote for Psychoanalytic Geographies (2016, pp. 15–19). I am grateful to Paul for allowing me to use these ‘pre‐Paul’ drafts for this book. Finally, Chapter 8, the conclusion, reworks short passages of material taken from ‘The Troubled Spaces of Frantz Fanon’ (published in Thinking Spaces , edited by Mike Crang and Nigel Thrift, in 2000, pp. 260–277). In general, I have retained the empirical stories within these previously published papers, but they have been re‐purposed, up‐cycled or re‐gifted (depending upon how you look at it). I therefore thank the publishers of the journals and the books for their permission to reprint previously published material.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the preceding list and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

This book is dedicated to Ben Robinson who, despite his most determined efforts, still suffers from geography.

North London

April 2020

Chapter One Introduction: Bodies, Affects and Their Politicisation

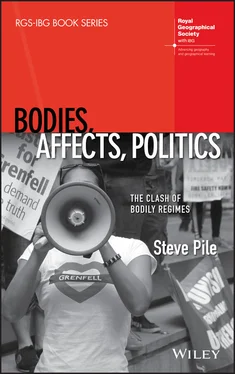

It is impossible to discuss the relationships between bodies, affects and politics in the abstract: that is, abstracted from the material and ideological conditions of their production, from the processes of politicisation and depoliticisation that bring bodies and affects into, or keep them away from, politics (to paraphrase Harvey, 1993, p. 41). To introduce this book, then, I will start with the story of a particular neighbourhood in West London. It is a story worth telling in its own right, for it involves social murder, as Labour MP John McDonnell put it. However, my purpose is to show how bodies, affects and politics have been entangled at various moments in the area’s recent history. But, more than this, I want to argue that there are different regimes of bodies, affects and politics operative in these moments – and it is in the clash between these regimes that different forms of politics can emerge. The problem that animates this book, then, is this: how are we to understand these regimes and what are we to make of them?

Lancaster West Estate, North Kensington

In 1972, work began constructing the Lancaster West Estate in North Kensington, London. The Estate was intended to redevelop part of the Notting Hill area, which had become notorious for its slums, poverty and criminality. This reputation has, for decades, been racialised. Since the HMT Empire Windrush first docked (in 1948), the neighbourhood’s cheap rooms for rent had proved attractive to new immigrants from the Caribbean (see Phillips and Phillips 2009). Notting Hill also attracted ruthless slum landlords, such as (most infamously) Peter Rachman. By the 1950s, local white people, especially working‐class Teddy Boys, were starting to display hostility towards black people moving into the area. In the summer of 1958, there were increasing attacks on black people as well as the rise of right‐wing groups, such as the White Defence League; its slogan, ‘Keep Britain White’. On Sunday 24 August 1958, armed with iron bars, table legs, crank handles, knives and an air pistol, a gang of white young men bundled into a battered car and drove around Notting Hill for three hours on what they called – in a ghastly echo of lynching culture in the South of the United States – a ‘nigger hunt’ (‘The Nigger Hunters’, Time Magazine , 29 September 1958, p. 27). They attacked six Caribbean men in four separate incidents: nine of the gang were arrested the following day in the nearby White City estate, after their car was spotted by police. (Later, in September 1958, to their shock, they were each sentenced to four years in prison by Mr Justice Cyril Salmon.)

The following Friday, 29 August 1958, Majbritt Morrison, a white Swedish woman (who would later author Jungle West 11 about her experiences) was arguing with her Jamaican husband, Raymond Morrison, outside Latimer Road tube station (which is situated on the western edge of the Lancaster West Estate). A crowd of white people gathered to protect a white woman from a black man (see Dawson 2007, pp. 27–29), despite Majbritt herself not needing nor wanting to be defended. A scuffle broke out amongst the gathering crowd, Raymond and some of Raymond’s Caribbean friends. On Saturday 30 August, a gang of white youths spotted Majbritt leaving a dance, recognising her from the evening before they started hurling racist abuse – and milk bottles. Someone hit Majbritt in the back with an iron bar. Yet, she stood her ground and fought back, but, when she refused to leave the scene, the police arrested her. The situation quickly escalated. Soon, a 200‐strong mob of young white men was rampaging through the streets of north Notting Hill (half a mile or so to the east of the tube station), armed with knives and sticks, shouting ‘down with niggers’ and ‘we’ll murder the bastards’ (reported in The Independent , 29 August 2008 and The Guardian , 24 August 2002, respectively). The mob attacked police with a shower of bottles and bricks. This led to five nights of constant rioting (until 5 September), fuelled by the arrival of thousands of white people from outside the area, and by the retaliation of the local Jamaican population, which eventually armed themselves with machetes, meat cleavers and Molotov cocktails.

Читать дальше