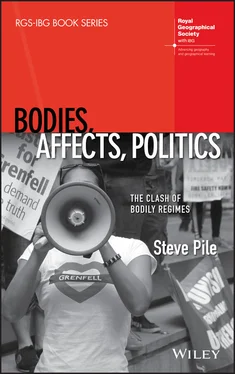

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Name: Pile, Steve, 1961– author. Title: Bodies, affects, politics : the clash of bodily regimes / Steve Pile. Description: Hoboken, NJ : Wiley, 2021. | Series: RGS‐IBG book series | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020038677 (print) | LCCN 2020038678 (ebook) | ISBN 9781118901984 (cloth) | ISBN 9781118901977 (paperback) | ISBN 9781118901953 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781118901946 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Human body–Social aspects. | Human body–Political aspects. | Social distance–History–21st century. | Communities–History–21st century. Classification: LCC HM636 .P48 2021 (print) | LCC HM636 (ebook) | DDC 306.4–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038677LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038678

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Image: Justice for Grenfell protest (Saturday 16th June 2018) featuring Love4Grenfell logo tee‐shirt designed by Charlie Crockett and Cheshona Hart © Steve Pile

The information, practices and views in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

The RGS‐IBG Book Series only publishes work of the highest international standing. Its emphasis is on distinctive new developments in human and physical geography, although it is also open to contributions from cognate disciplines whose interests overlap with those of geographers. The Series places strong emphasis on theoretically‐informed and empirically‐strong texts. Reflecting the vibrant and diverse theoretical and empirical agendas that characterize the contemporary discipline, contributions are expected to inform, challenge and stimulate the reader. Overall, the RGS‐IBG Book Series seeks to promote scholarly publications that leave an intellectual mark and change the way readers think about particular issues, methods or theories.

For details on how to submit a proposal please visit: www.rgsbookseries.com

Ruth Craggs, King's College London, UK

Chih Yuan Woon, National University of Singapore

RGS‐IBG Book Series Editors

David Featherstone, University of Glasgow, UK

RGS‐IBG Book Series Editor (2015–2019)

Today, London is quieter than I have ever known it to be. The skies above are undisturbed by the noise of planes, no white vapour trails scratching the brilliant blue. The East Coast mainline normally rumbles with heavy goods trains punctuated by the shattering sound of fast inter‐city services, but not for the last two weeks. Normally, the day is interrupted by at least one low‐level fly‐over by a police helicopter, but not recently. The hum of traffic is notably subdued, as when snow falls, muffling sound, preventing vehicles from moving around the city. This quieting, however, is not a sign that the city is calmer, rested, at peace. Instead, the quiet feels more like frustration, determination and a low‐level anxiety that threatens to break cover.

As I wait patiently in the queue at my local supermarket, I am paying attention to who is – and who is not – wearing face coverings, but especially noting the facemasks. Facemasks are as sure a measure of the level of anxiety and fear in the city as the intensification of the policing of bodies (which is not only conducted by the police). I know I am 2 metres back from the person in front of me and that the person behind me is 2 metres away from me. I know because the pavement has suddenly become covered in sticky tape that tells bodies where they should be. Sometimes, there are big stickers with footprints; ‘stand here’ they instruct. I am self‐policing. I stand where I should, as do most people. Some people do not. They are policed: the supermarket has employed a company that, judging by their jackets, normally stewards entertainment events. A woman in a high vis jacket, continually adjusting her ill‐fitting facemask, waves us forward, then halts us, with only the use of her right arm. The queue dutifully obeys these wordless commands.

I reach the point where the orderly queue awkwardly passes the store’s exit. At first I do not notice the man leaving the supermarket, but then I realise he’s walking backwards. A tall security guard is escorting him out. ‘Don’t touch me’! the man shouts. ‘Don’t fucking touch me! Don’t fucking touch me! Don’t fucking touch me’! he screams. The security guard puts his hands up, as if to nudge the man out of the exit. The man jumps back, and yells some more. The security guard says nothing; he does not touch the man; but, he keeps moving half steps forward, shepherding the man out. Now, another security guard appears. And some supermarket employees. They say little, but make ‘calm down’ gestures with their hands. The man yells: ‘You’ve got anger issues, you. You’ve got fucking anger issues. Fucking anger issues, you’! The second security guard intervenes, says something in the ear of the first security guard, who then starts to leave. ‘I’ll fucking have you’, the man yells after him. ‘Come and have some of this’! he shouts as he also starts to leave. We, in the queue, who witness this look at each other, over the top of our facemasks: we have not yet learned to communicate with just our eyes, but they all seem to be rolling. Our eyes seem to be saying: ‘We live in mad times’. And, I think to myself, the proper response to living in mad times is to be mad. In a short few months, we will learn that security guards are amongst the most vulnerable occupations to COVID‐19 – and that black and minority ethnic people are overrepresented in these occupations. It matters that the woman security guard is Black and the men from the store are Turkish and Asian.

Inside the supermarket, there’s clear evidence of fear. Vast swathes of the shelves are empty: there’s no toilet paper, pasta, tinned foods, surface cleaners of any kind, eggs, flour or paracetamol. People wander slowly past the shelves because this is something to see: it is a sign of the times, so worth looking at. People mutter about ‘panic buying’, but, of course, the panic buyers are the sensible buyers as they are the ones who anticipated the panic buying. Panic has been normalised. As I leave, a man outside is yelling ‘This is Great Britain! Tell the truth! Tell the Truth’! He is holding a black leather‐bound book, with gold lettering that I make no effort to read. ‘We tell the truth in Great Britain’, he screams at no one in particular. I avoid eye contact as he passes. ‘Tell the truth’! I hear him shouting as I disappear across the road. As I walk, I listen, but there’s no clue to what truth he means. Part of me would like to know, but a larger part is afraid to find out.

I write (and rewrite) in a moment of indeterminacy; we do not know when the COVID‐19 crisis will end, nor what it will have done to bodies, affects or politics. People want it over. They want to know when it will end and what the plan is. There is a lot of talk of curves, peaks and plateaus, and second waves; each day, there’s an accountancy of the dead, with bar graphs and imagined bell curves. The virus has not told us what its plan is: we cannot reason with it, so it feels like the disaster is the fault of the virus, as if it were a terrorist or a mugger. Yet, it is a mistake to think that the coronavirus is a natural disaster or to anthropomorphise it. That said, we do not yet know what kind of disaster it is. Indeed, it seems to be a disaster many times over. Every death is an individual, a person dying unforgivingly, causing inexpressible loss and grief for untold families, friends, colleagues. So many are dying, so few stories make the news. Yet, we are also told it is an economic disaster. We are told it will change everything. A disaster impacting every corner of our lives. (Although, apparently, it’s been good for the planet. And some are profiting beyond their wildest dreams.) The coronavirus is accreting ever more meanings, as its impacts multiply and intensify. We do not know which of its many meanings will persist and which will not. We do not know how the necropolitics to follow after the coronavirus will play out. We live, right now, not knowing. I am guessing, perhaps hoping, none of the above surprises you.

Читать дальше