Index

CONTRIBUTORS

Eman Allam, BDS, PHD, MPH

Postdoctoral Fellow

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Facial Genetics

Indiana University School of Dentistry

Indianapolis, Indiana

Mohamed Bazina, BDS, MSD

Assistant Clinical Professor

Department of Orthodontics

University of Kentucky

Adjunct Assistant Professor

Department of Orthodontics

School of Dental Medicine

Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

Eric Dellinger, DDS, MSD

Private Practice Limited to Orthodontics

Angola, Indiana

Paul C. Edwards, DDS, MSC

Professor

Department of Oral Pathology, Medicine & Radiology

Indiana University School of Dentistry

Indianapolis, Indiana

Tarek Elshebiny, BDS, MSD

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Orthodontics

School of Dental Medicine

Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

James Geist, DDS, MS

Professor

Department of Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences

Director, Oral and Maxillofacial Imaging Center

University of Detroit Mercy

Detroit, Michigan

Ahmed Ghoneima, BDS, PHD, MSD

Chair and Associate Professor, Orthodontics

Hamdan Bin Mohammed College of Dental Medicine

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Adjunct Faculty

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Facial Genetics

Indiana University School of Dentistry

Indianapolis, Indiana

Katherine Kula, MS, DMD, MS

Professor Emeritus

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Facial Genetics

Indiana University School of Dentistry

Indianapolis, Indiana

Manuel Lagravère, DDS, MSC, PHD

Associate Professor

Division of Orthodontics

Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry

University of Alberta

Edmonton, Alberta

Connie P. Ling, DDS, MSC

Private Practice Limited to Orthodontics

Toronto, Ontario

Juan Martin Palomo, DDS, MSD

Professor and Residency Director

Department of Orthodontics

Director of the Craniofacial Imaging Center

School of Dental Medicine

Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

Leena Palomo, DDS, MSD

Associate Professor

Department of Periodontology

School of Dental Medicine

Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

Edwin T. Parks, DMD, MS

Professor

Department of Oral Pathology, Medicine & Radiology

Indiana University School of Dentistry

Indianapolis, Indiana

Ali Z. Syed, BDS, MHA, MS

Assistant Professor

Director of Radiology

School of Dental Medicine

Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

Achint Utreja, BDS, MS, PHD

Assistant Professor and Director, Pre-Doctoral Orthodontics

Director, Mineralized Tissue and Histology Research Laboratory

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Facial Genetics

Indiana University School of Dentistry

Indianapolis, Indiana

1

Introduction to the Use of Cephalometrics

Katherine Kula, MS, DMD, MS Ahmed Ghoneima, BDS, PhD, MSD

Cephalometrics refers to the quantitative evaluation of cephalograms, or the measuring and comparison of hard and soft tissue structures on craniofacial radiographs. It is an evolving science and art that has been woven into orthodontics and the treatment of patients. Cephalograms are an integral part of orthodontic records and are typically used for almost all orthodontic patients. The cephalometric analysis or evaluation helps to confirm or clarify the clinical evaluation of the patient and provide additional information for decisions concerning treatment.

The American Association of Orthodontists (AAO) developed the current Clinical Practice Guidelines for Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 1which recommend that initial orthodontic records include examination notes, intraoral and extraoral images, diagnostic casts (stone or digital), and radiographic images. These radiographic images include appropriate intraoral radiographs and/or a panoramic radiograph as well as cephalometric radiographs. A three-dimensional cone beam computed tomograph (3D CBCT) can be substituted for a cephalometric radiograph; however, the routine use of a CBCT is not generally required in orthodontics, so cephalometric radiographs are the current standard.

The AAO Clinical Practice Guidelines 1also recommend evaluating the patient’s treatment outcome and determining the efficacy of treatment modalities by comparing posttreatment records with pretreatment records. Posttreatment records may include dental casts; extraoral and intraoral images (either conventional or digital, still or video); and intraoral, panoramic, and/or cephalometric radiographs depending on the type of treatment and other factors. Many orthodontists also take progress cephalograms to determine if treatment is progressing as expected. In addition, board certification with the American Board of Orthodontics requires cephalograms and an understanding of cephalometry to explain the decisions for diagnosis, treatment, and the effects of growth and orthodontic treatment. Therefore, it is paramount that orthodontists understand how to use cephalometrics in their practice.

Basics of Cephalometrics

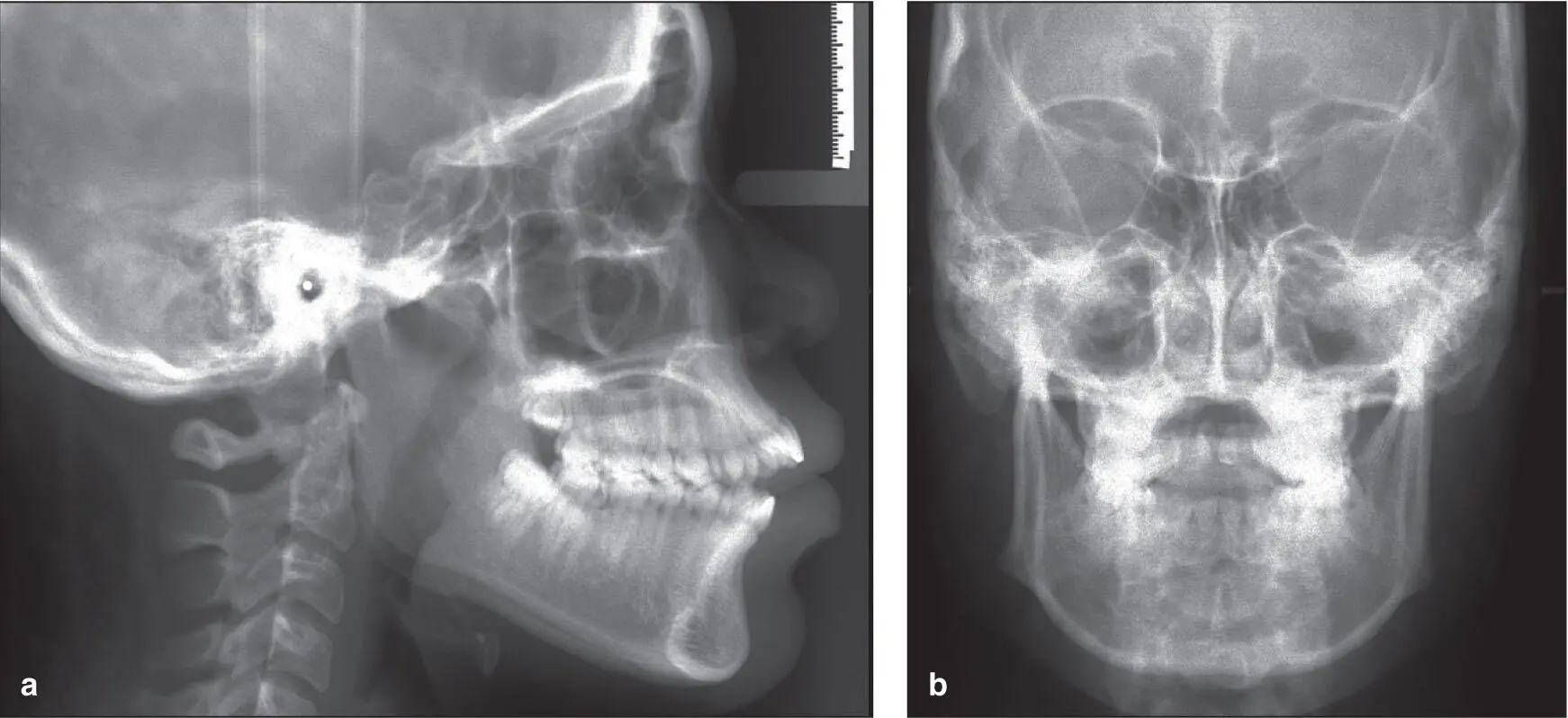

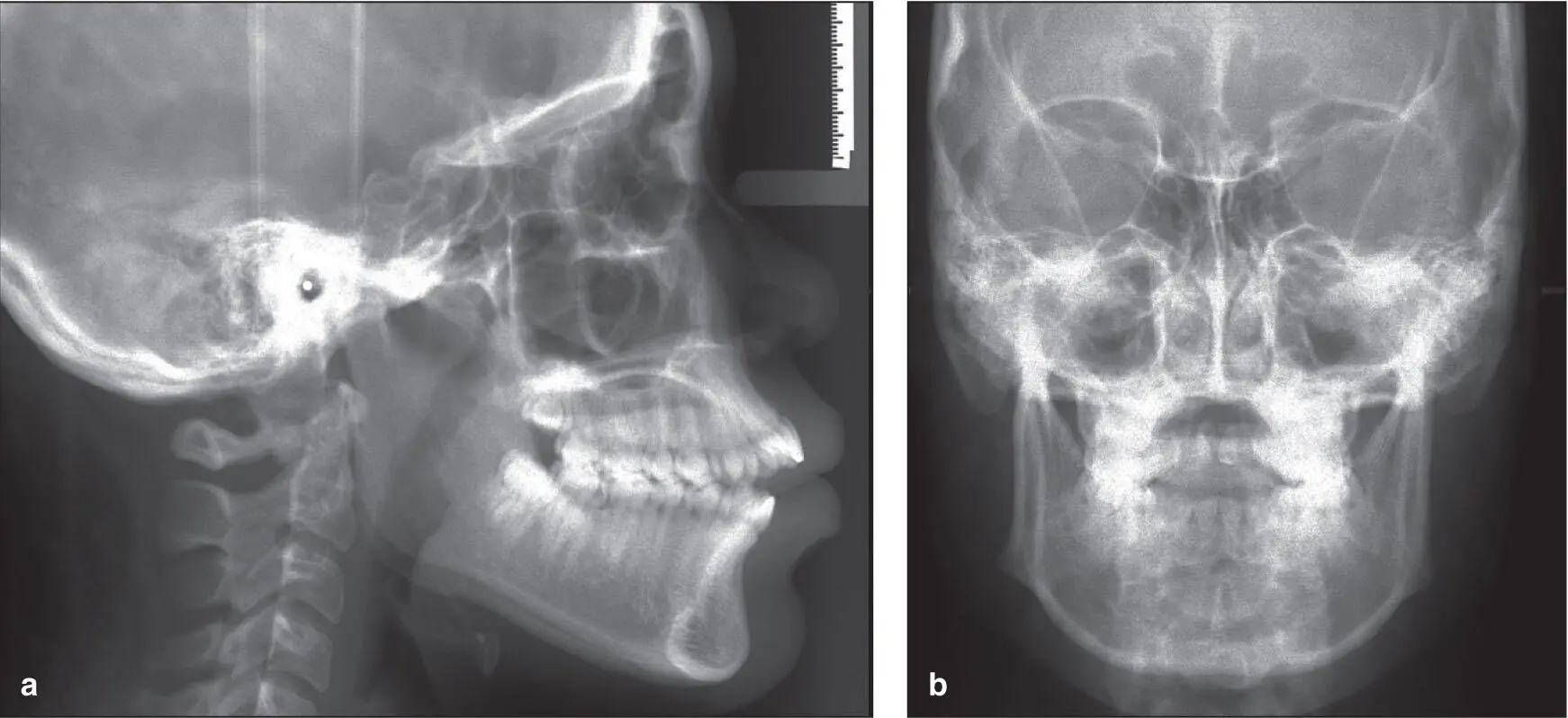

Cephalometrics is used to assist in (1) classifying the malocclusion (skeletal and/or dental); (2) communicating the severity of the problem; (3) evaluating craniofacial structures for potential and actual treatment using orthodontics, implants, and/or surgery; and (4) evaluating growth and treatment changes of individual patients or groups of patients. In general, a lateral cephalogram shows a two-dimensional (2D) view of the anteroposterior position of teeth, the inclination of the incisors, the position and size of the bony structures holding the teeth, and the cranial base ( Fig 1-1a). A cephalogram can also provide a different view of the temporomandibular joint than a panoramic radiograph and a view of the upper respiratory tract.

Fig 1-1 (a and b) Lateral and frontal cephalograms.

In addition, cephalograms aid in the identification and diagnosis of other problems associated with malocclusion such as dental agenesis, supernumerary teeth, ankylosed teeth, malformed teeth, malformed condyles, and clefts, among others. They have also been used to identify pathology and can give some indication of bone height and thickness around some teeth. However, they are not very useful in identifying dental caries, particularly initial caries, and periodontal disease, so bitewing radiographs and periapical radiographs are needed for patients who are caries susceptible or show signs of periodontal disease. While some asymmetry can be diagnosed using a lateral cephalogram, an additional frontal cephalogram ( Fig 1-1b) is needed to better identify which hard tissue structures are involved in the asymmetry.

Of course all of these conventional radiographs are 2D images. A 3D CBCT can replace multiple 2D radiographs and can allow the entire craniofacial structure to be viewed from multiple aspects (x, y, z format) with one radiograph ( Fig 1-2). Intracranial and midline facial structures can be viewed without overlying confounding structures, and bilateral structures can be viewed independently. While the worldwide transition from 2D to 3D imaging is occurring quickly, it is still important for clinicians to understand what has been used for decades (2D), what additional 3D information is needed, and the limitations and potential of 3D imaging.

Читать дальше