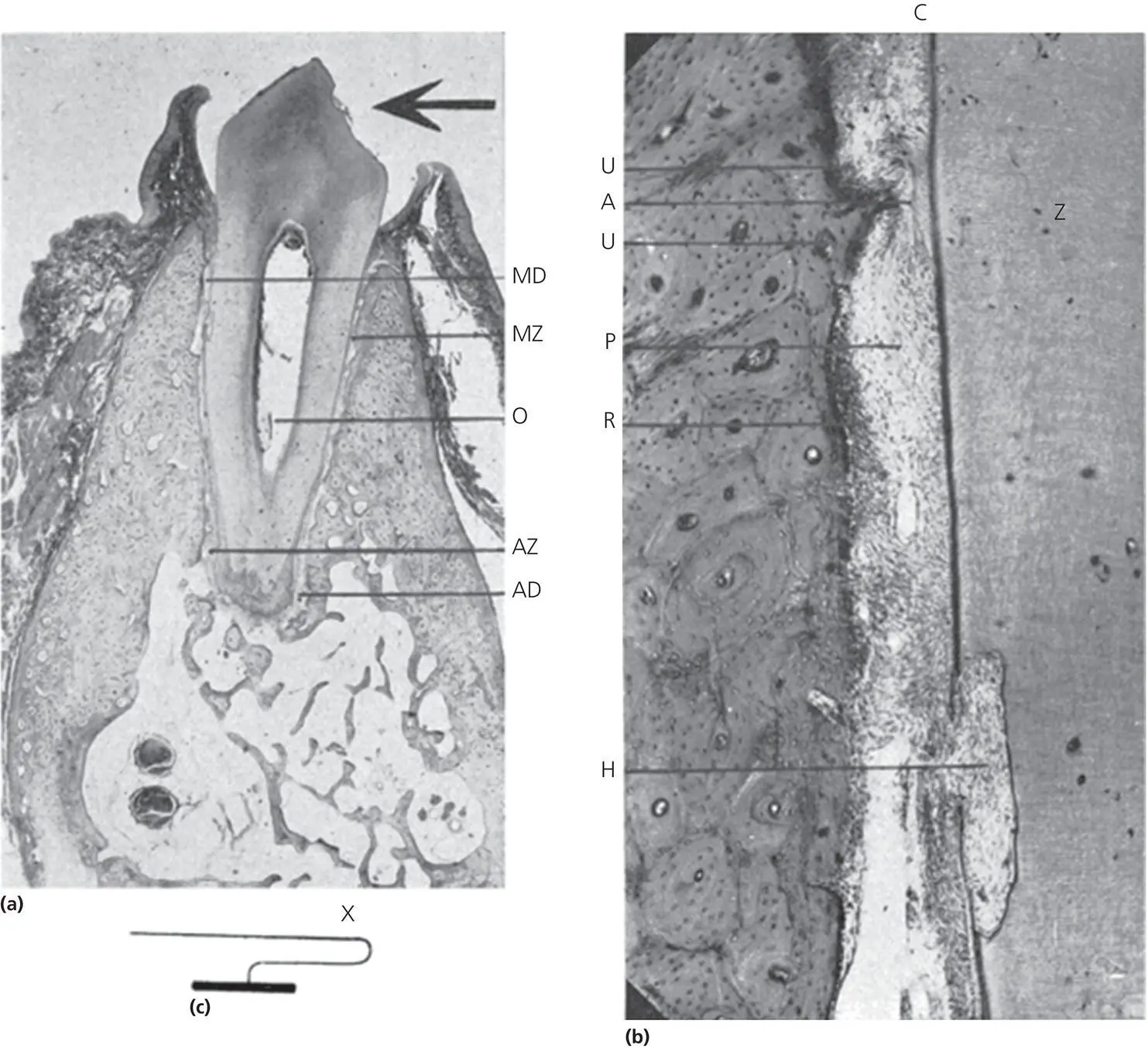

Third degree of biologic effect ( Figure 2.9). The force is fairly strong; sustaining increased pressure in the blood capillaries of the compressed PDL. At these areas, suffocation of the strangled PDL develops, followed by resorption of the necrotic tissue, including the dental root surfaces. This resorption takes an impetuous course and attacks also those parts of the surface of the root, the vitality of which may be injured by the pressure. After the force ceases, there will be anatomic and functional resolution of integrity of the PDL and alveolar bone, with resorption of roots frequently progressing into the dentin.

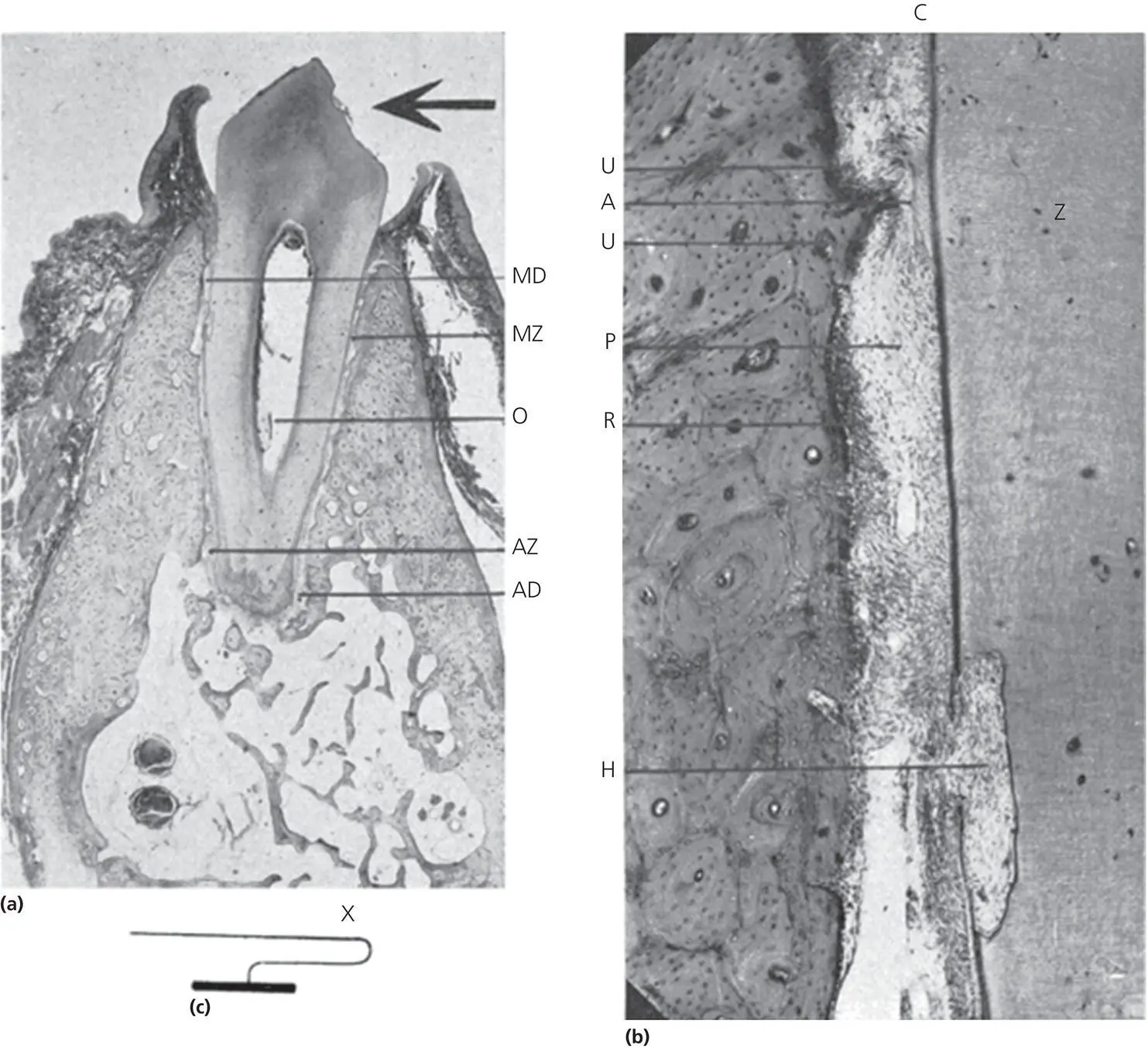

Fourth degree of biologic effect ( Figure 2.10). The force is strong, squeezing the strangled PDL, and the tooth touches the bone after the soft tissues are crushed. Alveolar bone resorption occurs in the periphery of the hyalinized PDL zones, as well as in bone marrow cavities near the compressed PDL. However, this situation is associated with a high risk of severe alveolar bone and root resorption, and damage to tissues of the dental pulp. In some cases, ankylosis of the tooth with the alveolar bone may occur.

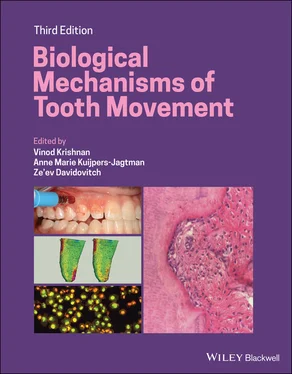

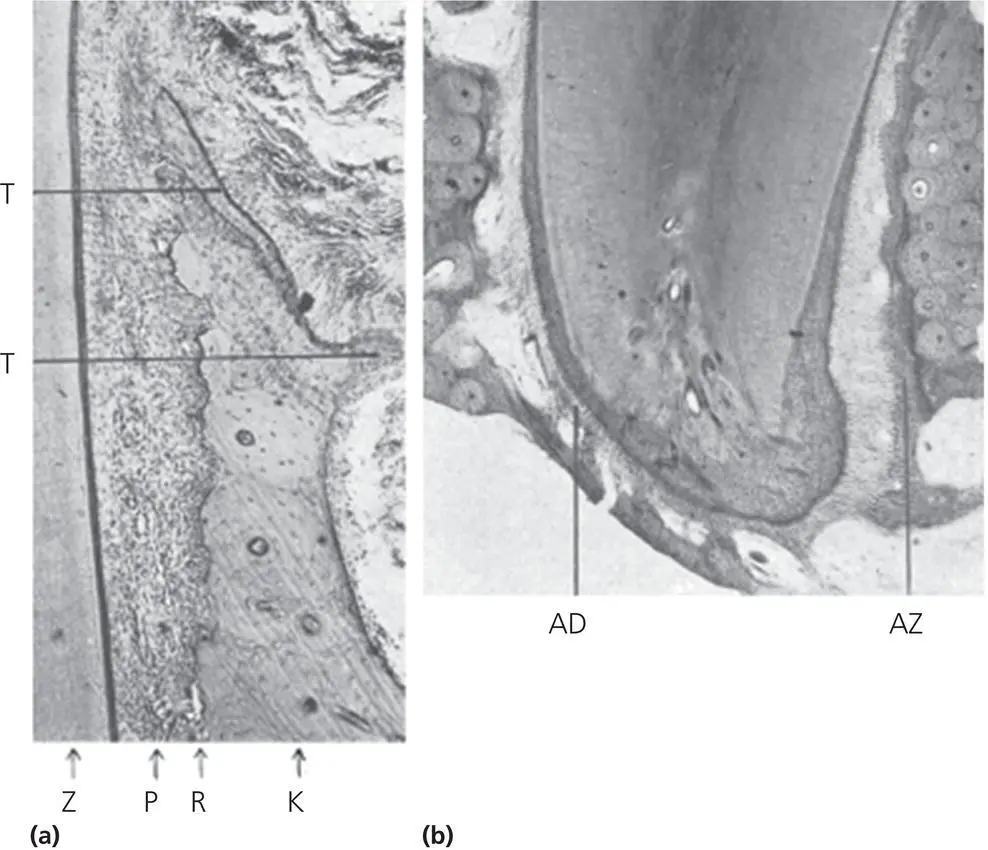

Figure 2.8 Second degree of biologic effect seen on the (a) marginal side of PDL pressure side of tooth movement as portrayed in Schwarz (1932). Z, tooth; P, periodontium; R, line or resorption; K, old alveolar bone; T, newly formed bone on the outer periosteal surface of the alveolar bone. (b) Apex of the tooth shown. AZ, apical side of pull with newly formed bones; AD, apical side of PDL pressure.

(Source: Schwarz, 1932. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.)

Schwarz concluded “that the most favorable treatment is that which works with forces not greater than the pressure of blood capillaries.” He identified this pressure as 15–20 mmHg in man and most mammals, and calculated the optimal force level to be 20–26 g to 1 cm 2of root surface area, suggesting that these limits of pressure are critical, capable of generating a continuous resorption of alveolar bone in areas of pressure in the PDL. Schwarz postulated further that the width changes in the PDL alter the cell population and increases cellular activity. There is an apparent disruption of collagen fibers in the PDL, with evidence of cell and tissue damage. If one exceeds this pressure, compression could cause tissue necrosis through “suffocation of the strangulated periodontium.” Application of even greater force levels will result in obliteration of blood vessels, followed by cell death in the ischemic area, which will lead to alteration in the orientation of PDL fibers from horizontal to vertical. This change in orientation will appear as glassy in nature, when observed through the light microscope and is labeled as hyalinization. There will be hyperemia in the area surrounding the necrotic area, which produces tenderness to the tooth. This hyperemia is considered to be essential to the resolution of the problem and speeding up the recovery phenomenon. The resolution of the problem starts when cellular elements such as macrophages, foreign body giant cells, and osteoclasts from adjacent undamaged areas invade the necrotic tissue ( Figure 2.10). These cells also resorb the underside of bone immediately adjacent to the necrotic PDL area and remove it together with the necrotic tissue (Schwarz, 1932).

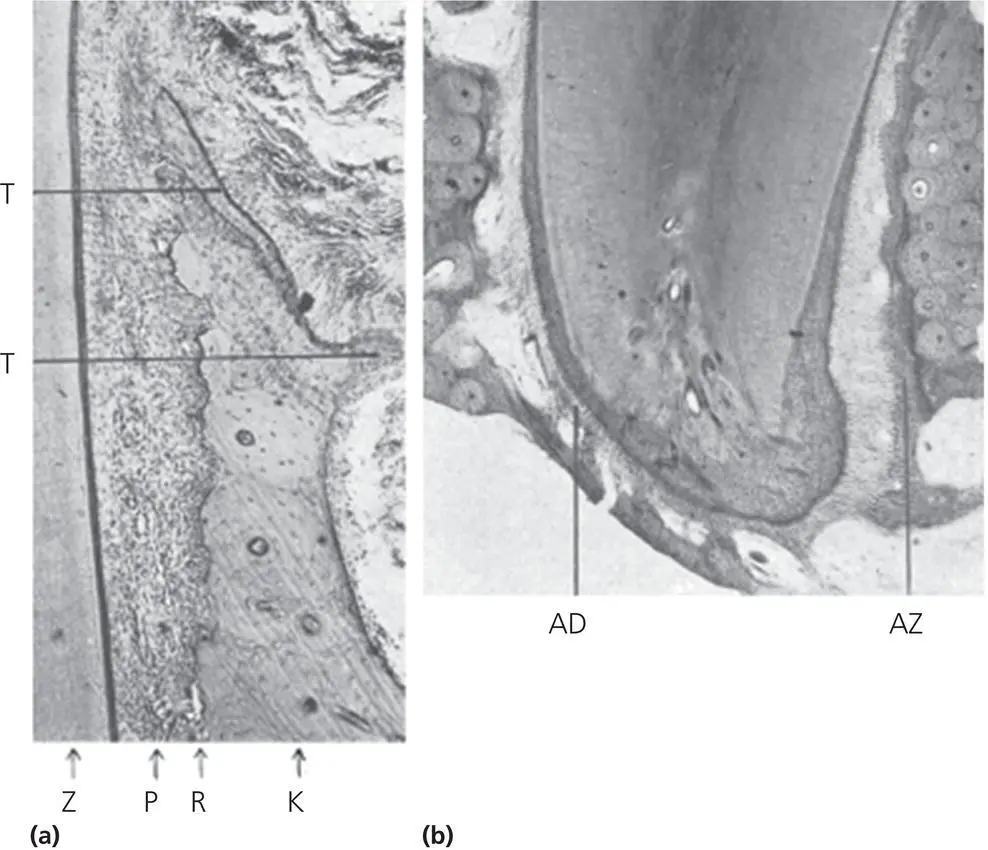

Figure 2.9 Third degree of biologic effect as portrayed in Schwarz article (1932). (a) Shows MZ, marginal side of pull; MD, marginal side of pressure; 0, tilt axis; AZ, apical side of pull; AD, apical side of pressure. (b) Marginal side of pressure, greatly enlarged: Z, tooth (dentine); C, cementum; H, resorption cavity reaching far into the dentine; P, periodontium; R, line of resorption on the alveolar wall, densely covered by osteoblasts; early stages of regeneration; A, compressed area of the periodontium, no nuclei of cells; U, signs of undermining resorption. (c) Sketch of the spring. The point of application on the tooth is shown at X.

(Source: Schwarz, 1932. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.)

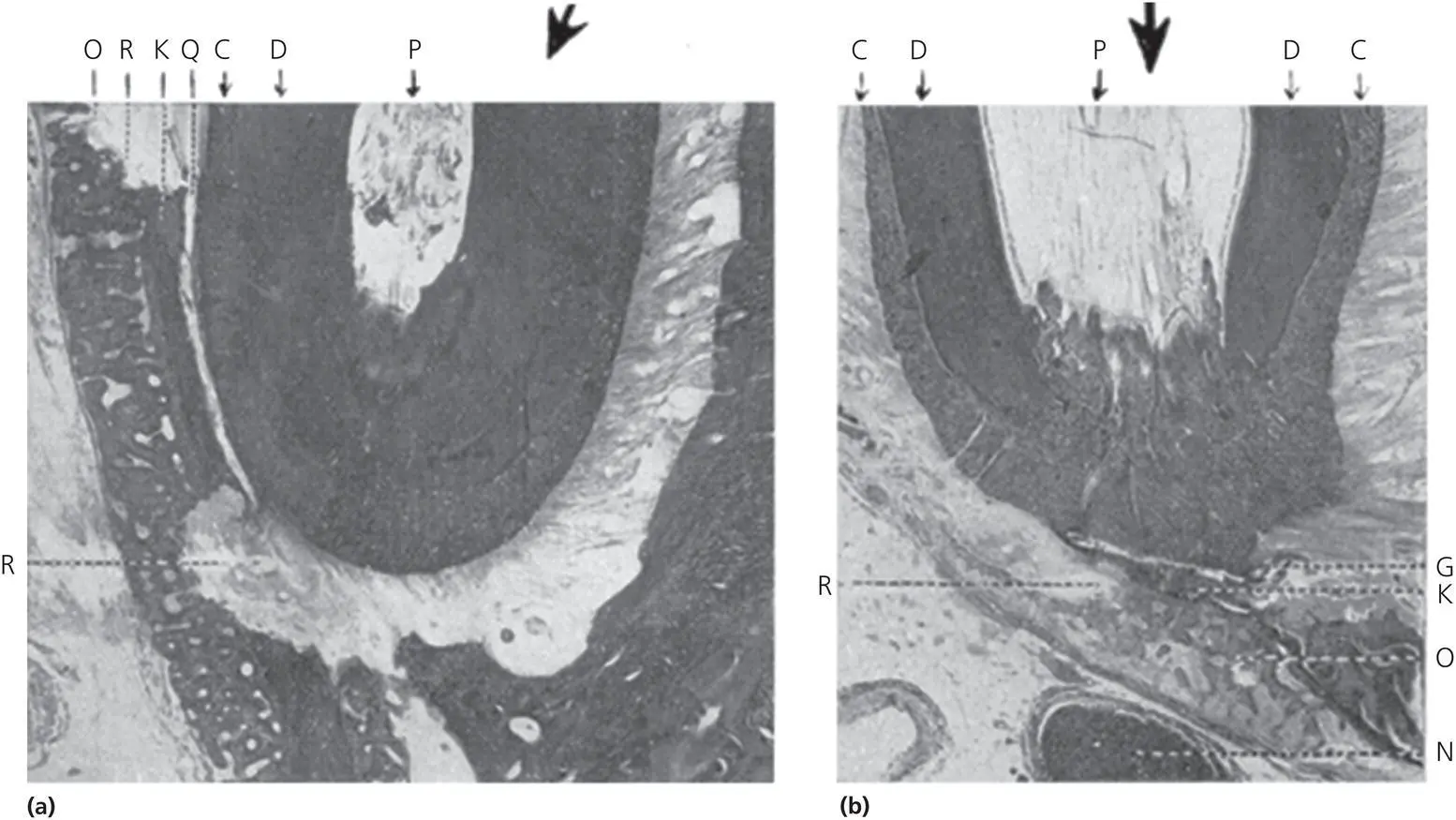

Figure 2.10 Fourth degree of biologic effect as portrayed in Schwarz article (1932) depicting osteophytes on the outer surface in the apical region. (a) The influence created by strong force applied in the direction of the arrow: P, pulp; D, dentine; C, cementum; K, old alveolar bone; O, osteophytes; Q, region of compression of the periodontium; R, region of resorption stretching over the newly formed osteophytes. (b) The osteophytes, O, were formed in the lumen of the canalis mandibulae (N, nervus mandibularis). At the region of compression, the old alveolar bone, K, is removed by undermining resorption, R. The young osteophytes were also attacked by the latter. Arrow and also P, C and D as in (a).

(Source: Schwarz, 1932. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.)

Through his writings, Schwarz tried to indicate the methodological differences between the approaches made by Sandstedt and Oppenheim ( Figure 2.11), and concluded that Oppenheim had euthanized his experimental animals several days after the appliance had been last activated, and Schwarz attributed this fact to the reason why Oppenheim saw only normal adaptation phenomena. Moreover, Oppenheim ignored the acute phase reactions and focused only on the stage of regeneration after the force had been exhausted. It seems more likely that what Oppenheim was describing was the response of cells of the periosteal and endosteal bone surfaces to the bending of the labial alveolar bone plate (Meikle, 2006).

Following Schwarz’s publication, Oppenheim performed additional studies on tissue reactions in mature monkeys ( Macaca rhesus ) to applications of light and heavy forces (Oppenheim, 1944). He concluded that with light forces, osteoclasts are mobilized at a very fast pace and attack bone by a uniform superficial lacunar resorption. These cells, called “primary osteoclasts,” stayed active in the site for almost 4 days ( Figure 2.12). In contrast, the use of heavy forces resulted in crushing of the PDL, with a cutoff in all its nutritional supplies, resulting in undermining resorption. The direction of bone resorption comes from unintended sources, with an inflow of osteoclasts from adjacent unaffected areas. These osteoclasts, called “secondary osteoclasts,” persist until the crushed PDL, bone, and cementum are removed ( Figure 2.12). Oppenheim further examined the hemorrhage formed by crushed blood vessels and found that the impaired nourishment along with encroachment of osteophytes and toxins from decomposed red blood cells lead to mobilization of osteoclasts from far off sites, called “tertiary osteoclasts” ( Figures 2.13and 2.14). All these cells were observed by application of higher amounts of force (240–360 g) to teeth. With these findings, Oppenheim advocated the use of intermittent forces, consisting of force application for a short period (1 day) followed by a rest period of longer duration (3 or 4 days). He considered this formula to be a biologic approach, but was later disproved by the evolution of mechanical devices of greater potential. He concluded that primary osteoclasts are the type, which is of great help to the orthodontist, and that only light forces can induce their production in abundance.

Читать дальше