1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...45 Network cable: The network cable physically connects the computers. It plugs into the network interface card (NIC) on the back of your computer.The type of network cable most commonly used is twisted-pair cable, so named because it consists of several pairs of wires twisted together in a certain way. Twisted-pair cable superficially resembles telephone cable. However, appearances can be deceiving. Most phone systems are wired using a lower grade of cable that doesn’t work for networks.For the complete lowdown on networking cables, see Chapter 2of this minibook. Network cable isn’t necessary when wireless networking is used. For more information about wireless networking, see Chapter 2of this minibook.

Network switch: Networks built with twisted-pair cabling require one or more switches. A switch is a box with a bunch of cable connectors. Each computer on the network is connected by cable to the switch. The switch, in turn, connects all the computers to each other.Most networks of more than a few dozen computers have more than one switch. In that case, the switches themselves are connected to each other with cable in a manner that allows all the computers to communicate with each other without regard to which switch they’re directly connected to. In the early days of twisted-pair networking, devices known as hubs were used rather than switches. The term hub is sometimes used to refer to switches, but true hubs went out of style sometime around the turn of the century.I explain much more about switches and hubs in Chapters 2and 3of this minibook.

Wireless access points: In a wireless network, most cables and switches are moot. Instead, radio takes the place of cables. The device that enables a computer to connect wirelessly to a network is called a wireless access point. A WAP is a combination of a radio transmitter and a radio receiver and has an integrated wired network port. The WAP must be connected to the network via a cable, but it allows wireless devices such as laptops, tablets, and phones to connect wirelessly.

Router: A device found in nearly all networks is a router, which is used to connect two networks — typically your internal network and the Internet. You’ll learn more about routers in Chapters 2and 3of this minibook.

Firewall: A firewall is an essential component of any network that connects to the Internet. The firewall provides security features that help keep cybercriminals out of your network.In most cases, the function of a firewall is combined with the function of a router in a single device called a firewall router. This makes sense because the firewall is a security wall between two networks (usually the Internet and your internal network). So, the router component links the two networks, while the firewall component provides security.In home networks or small office networks, it’s also common to combine the functions of firewall, router, WAP, and switch into a single device that’s usually called a wireless router or a Wi-Fi router. When you purchase such a device, check to make sure it has adequate firewall features and the correct number of switch ports for your wired devices.

Putting the Pieces Together

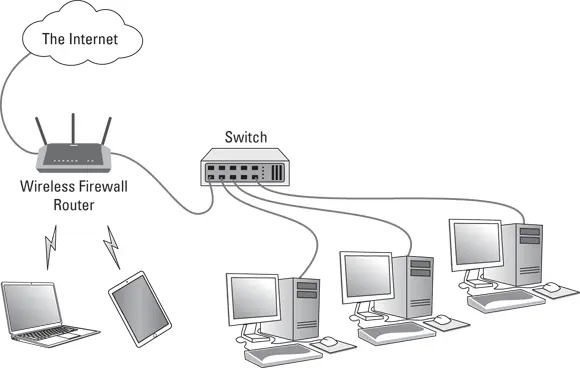

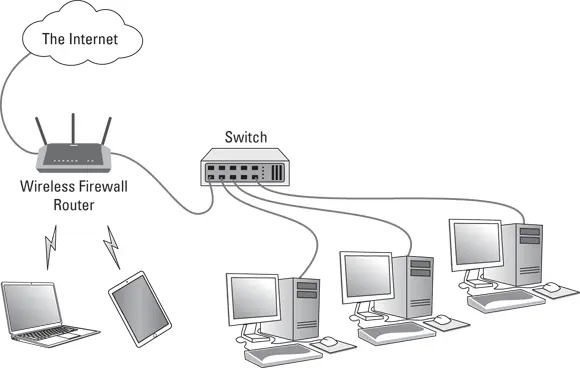

In a small network such as the one that was shown in Figure 1-1, a wireless router combines the function of firewall, router, switch, and WAP. This arrangement is fine for very small networks, but when you exceed the wired switch capacity of the wireless router, you’ll need additional components.

Figure 1-2 shows a network with a separate switch to connect multiple computers. Here, you can see that the wireless router connects to both the Internet and the switch. Several computers have wired connections to the switch, and wireless devices connect via the WAP that’s built in to the Wi-Fi router. The wireless router also provides the firewall function.

FIGURE 1-2:A network with a wireless router and a switch.

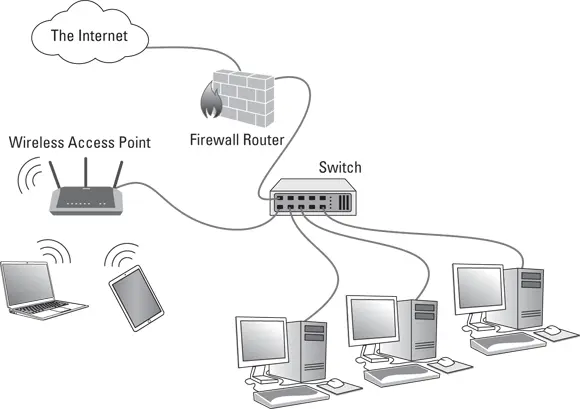

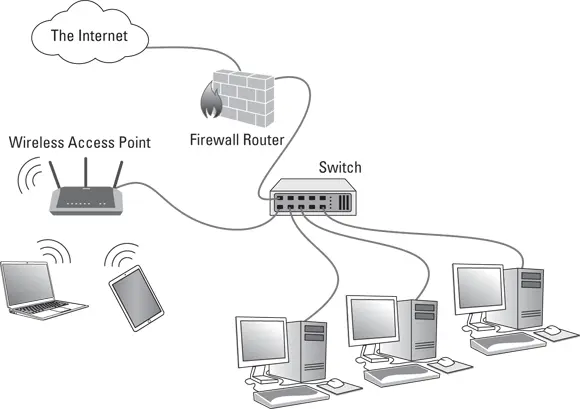

Figure 1-3 shows a more complicated setup, in which the WAP is separated from the router. Here, the router with its built-in firewall connects to the Internet and to the switch. As before, several computers have wired connections to the switch. In addition, the WAP has a wired connection to the switch, allowing wireless devices to connect to the network.

FIGURE 1-3:A network with a separate firewall router, switch, and WAP.

In Chapter 3of this minibook, you see examples of more complicated arrangements of these basic network components.

Networks come in all sizes and shapes. In fact, networks are commonly based on the geographical size they cover, as described in the following list:

Local area networks (LANs): In this type of network, computers are relatively close together, such as within the same office or building.Don’t let the descriptor “local” fool you. A LAN doesn’t imply that a network is small. A LAN can contain hundreds or even thousands of computers. What makes a network a LAN is that all its connected computers are located within close proximity. Usually a LAN is contained within a single building, but a LAN can extend to several buildings on a campus, provided that the buildings are close to each other (typically within 300 feet of each other, although greater distances are possible with special equipment).

Wide area networks (WANs): These networks span a large geographic territory, such as an entire city or a region or even a country. WANs are typically used to connect two or more LANs that are relatively far apart. For example, a WAN may connect an office in San Francisco with an office in New York. The geographic distance, not the number of computers involved, makes a network a WAN. If an office in San Francisco and an office in New York each has only one computer, the WAN will have a grand sum of two computers — but will span more than 3,000 miles.

Metropolitan area networks (MANs): This kind of network is smaller than a typical WAN but larger than a LAN. Typically, a MAN connects two or more LANs within the same city that are far enough apart that the networks can’t be connected via a simple cable or wireless connection.

It’s Not a Personal Computer Anymore!

If I had to choose one point that I want you to remember from this chapter more than anything else, it’s this: After you hook up your personal computer (PC) to a network, it’s not a “personal” computer anymore. You’re now part of a network of computers, and in a way, you’ve given up one of the key concepts that made PCs so successful in the first place: independence.

I got my start in computers back in the days when mainframe computers ruled the roost. Mainframe computers are big, complex machines that used to fill entire rooms and had to be cooled with chilled water. My first computer was a water-cooled Acme Hex Core Model 2000. (I’m not making up the part about the water. A plumber was often required to install a mainframe computer. In fact, the really big ones were cooled by liquid nitrogen. I am making up the part about the Acme Hex Core 2000.)

Mainframe computers required staffs of programmers and operators in white lab coats just to keep them going. The mainframes had to be carefully managed. A whole bureaucracy grew up around managing them.

Mainframe computers used to be the dominant computers in the workplace. Personal computers changed all that: They took the computing power out of the big computer room and put it on the user’s desktop, where it belongs. PCs severed the tie to the centralized control of the mainframe computer. With a PC, a user could look at the computer and say, “This is mine — all mine!” Mainframes still exist, but they’re not nearly as popular as they once were.

Читать дальше