Figure 1.4 Endoscopic biopsy forceps in the open position. The needle‐like pin in the center holds the tissue in place so one to two samples can be obtained per pass.

Figure 1.5 Micro biopsy forceps <1 mm in diameter, which can be passed through specialized endoscopes into the bile duct, pancreas duct, or via 19‐gauge needles for extraluminal tissue sampling.

Source : Boston Scientific Corporation with permission.

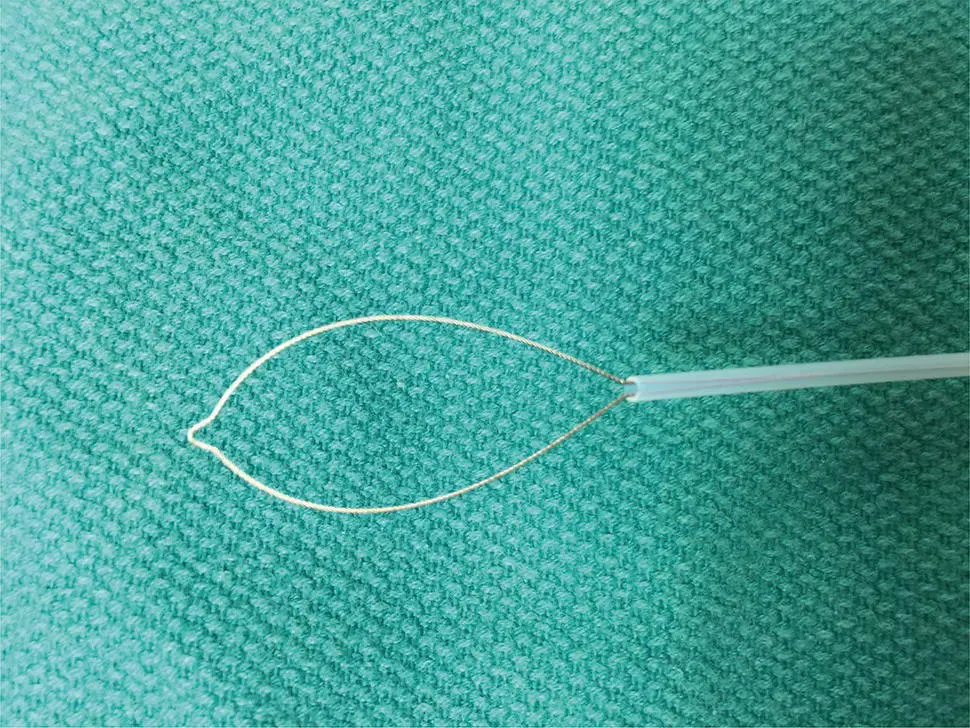

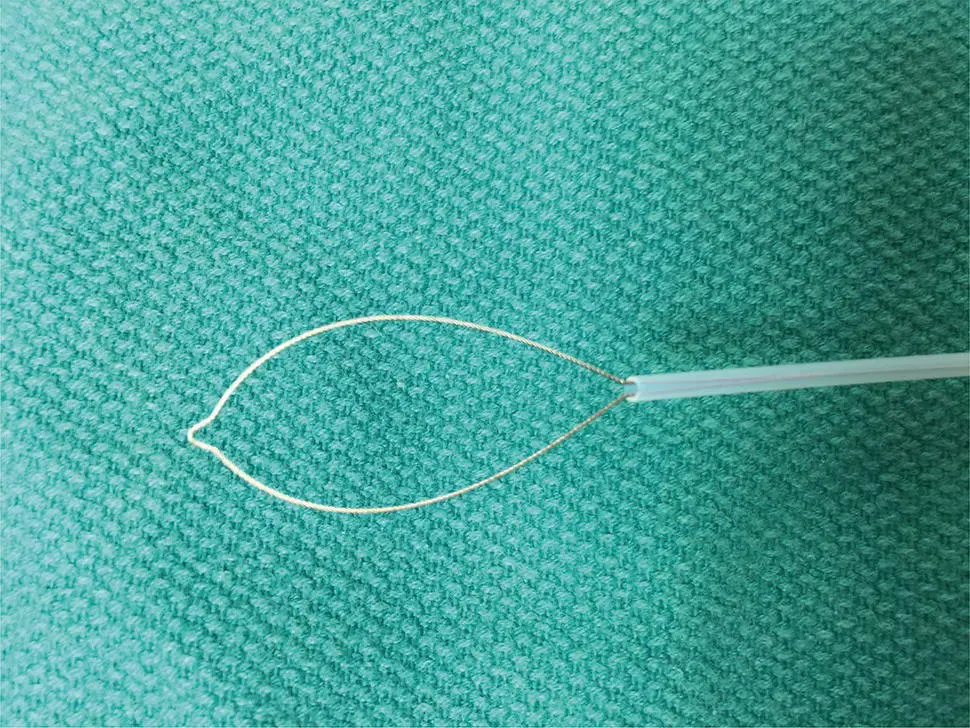

Figure 1.6 Endoscopic snare for polypectomy. The wire loop is extended in the open position outside the plastic sheath. When closed, the wire loop is strangulated and resects the polyp tissue.

Figure 1.7 Endoscopic cytology brush. Note the abrasive brush extended beyond the protective plastic sheath.

Endoscopic snare devices have also been widely used for resection of polypoid as well as flat lesions throughout the gastrointestinal tract. They have been remarkably versatile and effective over the past four decades. Endoscopic snares typically involve a metallic wire, which may braided or monofilament ( Figure 1.6).

A wire loop is generally constrained within a small caliber plastic catheter. At the distal end of the catheter, the wire loop can be opened to various sizes to grasp and resect polyps of different sizes. Typical sizes include loops 5–30 mm in diameter. There are numerous different shapes including oval, hexagonal, and asymmetric “duck bill.” Snares also come in various degrees of stiffness, which allow resection of lesions of many shapes and sizes. Tissue can be resected with mechanical closure alone (so‐called “cold snare”) or with mechanical plus electrosurgical cutting (“hot snare”). Recent studies suggest that cold snare is associated with lower risk of bleeding and bowel wall injury.

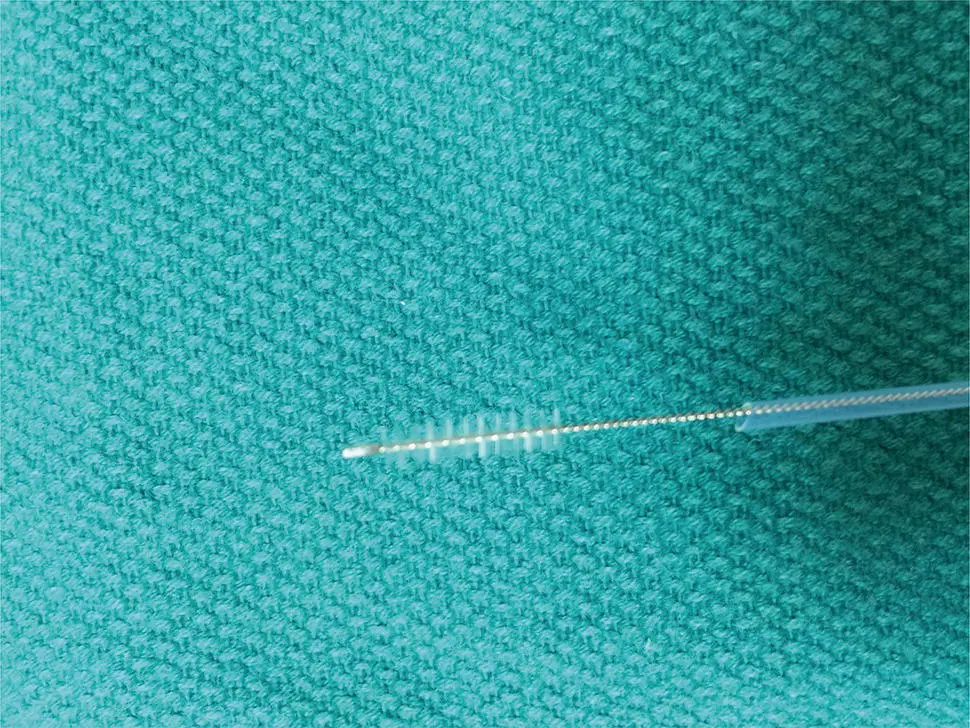

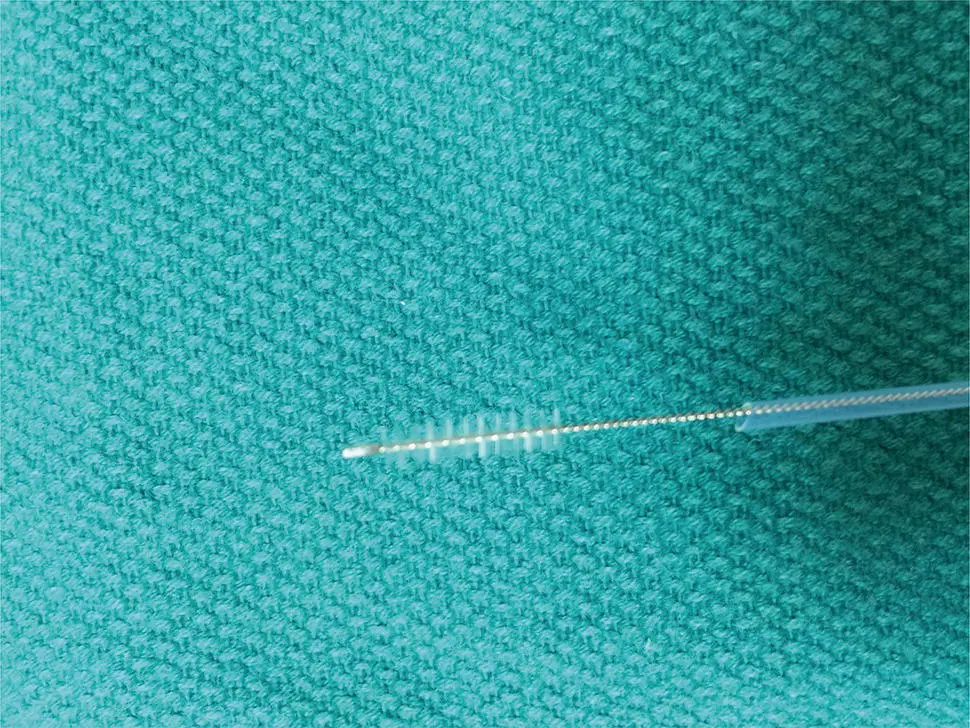

Endoscopic Brush Cytology

Abrasive brush cytology has been used in many different fields of tissue sampling. Typical endoscopic brush is constrained within a plastic catheter similar to endoscopic snares ( Figure 1.7).

After passing through the accessory channel of the endoscope, the abrasive brush is exposed and rubbed against the area of tissue sampling. This is most commonly applied to obtain specimens for microbiology, particularly fungal specimens. These have also been widely applied in the biliary tract for sampling of suspicious biliary strictures. More recent advances include a highly abrasive wide‐area tissue sampling system that has been recently studied and Barrett's esophagus as an alternative to pinch forceps, as well as nonendoscopic abrasive sponge sampling, which has the potential to offer inexpensive population‐based screening for esophageal neoplasia ( Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 Nonendoscopic abrasive cytology brush.

Source : From Kadri, S.R., Lao‐Sirieix, P., O'Donovan, M. et al. (2010). Acceptability and accuracy of a non‐endoscopic screening test for Barrett's oesophagus in primary care: cohort study. BMJ 341: c4372. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4372. Open access article.

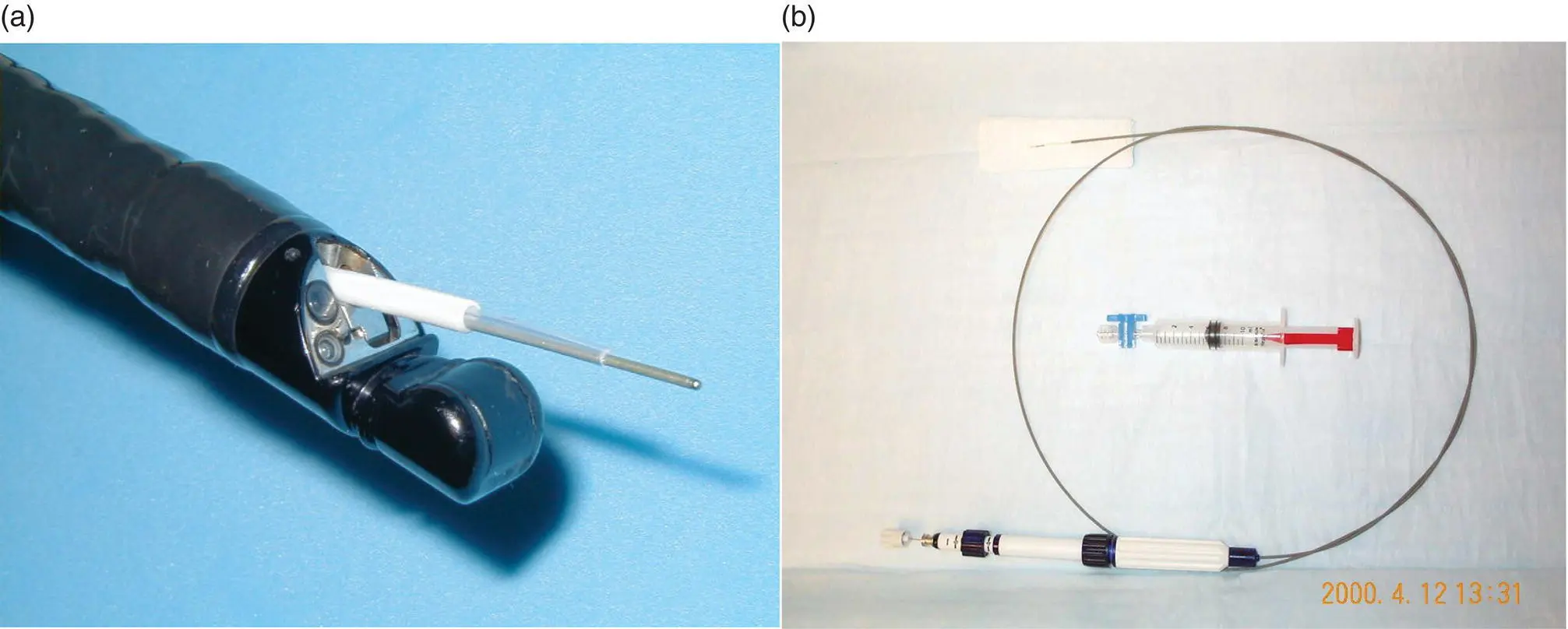

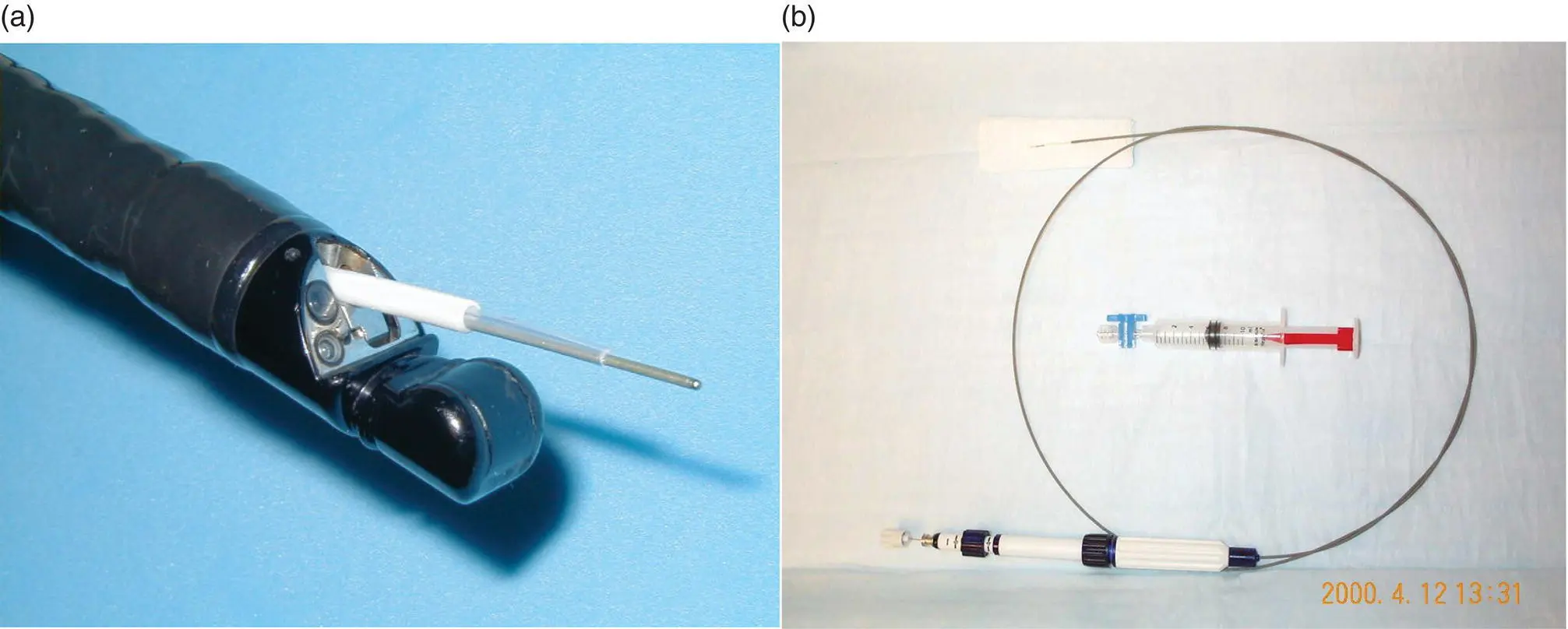

Endoscopic Fine‐Needle Aspiration (FNA) Devices

The most common application of FNA devices in endoscopy is endoscopic ultrasound‐guided tissue sampling (EUS‐FNA). The development of endoscopic ultrasound in the 1970s and 1980s significantly expanded the reach of endoscopic tissue sampling into the pancreas and other extraluminal organs such as lymph nodes and now virtually any organ within reach of the proximal or distal GI tract lumen ( Figure 1.9).

Other needle aspiration devices include biliary sampling needles often used in conjunction with forceps and brush sampling, or so‐called “triple sampling.” EUS‐FNA devices come in various sizes from 19‐ to 25‐gauge. These devices are typically attached to a handle, which allows the endoscopist to puncture and make to‐and‐fro movements within the target lesion and also apply negative pressure. With various methods, both cytologic and histologic material can be obtained through these needle devices. Recent efforts to develop Tru‐Cut devices have been met with variable success.

Tissue Processing in the Endoscopy Laboratory

An excellent recent review on the topic of tissue acquisition has been published by the American Society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. For most routine tissue sampling the biopsy material is placed in formalin and subsequently embedded in paraffin for histological analysis. Other specific preparations include sampling for microbiological evaluation, molecular or genetic testing, and electromicroscopy. These special samples should be handled according to local institutional guidelines. In general, samples that are obtained for culture should be obtained prior to placing forceps into formalin as formalin residue can destroy or inactivate live microbial tissue.

Figure 1.9 (a) and (b) Endoscopic ultrasound endoscope and guided fine‐needle aspiration (EUS‐FNA) device.

Most pinch biopsy samples are placed directly in formalin without orientation. This is also true for small polyps where the likelihood of invasive cancer is very low. The sample is placed directly into a small formalin jar. The needle or forceps should be rinsed if it comes in direct contact with formalin as subsequent contact with living tissue can cause chemical injury.

Increasingly, endoscopic resection is being used for definitive oncologic removal of precancerous and invasive lesions. In these cases it is advantageous to orient the specimen so that precise staging as well as margin assessment can be performed. A typical situation is in endoscopic resection of early neoplasia in the esophagus such as Barrett's esophagus. In this case a sample is frequently obtained through endoscopic mucosal resection. Large pieces of tissue, typically 1–2 cm in diameter, can be obtained to a depth of the submucosa. In this case the sample should be removed from the patient in a way that does not damage or distort the tissue. This is typically performed by suctioning the tissue into a distal attachment cap/hood and then removing the endoscope. Alternative retrieval devices include a modified snare with a protective net. These tissues should then be immediately oriented at the bedside typically by placing them on a paraffin or similar firm block. The tissue should be flattened typically with the mucosal side up and the edges carefully pinned so that the tissue remains flat ( Figure 1.10).

Cytology samples obtained from either brush or fine‐needle aspiration can be processed in a variety of ways. Most commonly these are prepared as thin smear on glass slides, which can be evaluated either immediately as an air‐dried sample stained with a modified Romanowsky stain, or as an alcohol‐fixed slide evaluated with Papanicolaou staining. It is often helpful to place additional excess material in a cytological preservative or formalin. Special handling is required for samples where lymphoproliferative disease is considered. Typically these include cytological preservatives such as Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium that allow subsequent flow cytometry. As a practical matter, placement in such a preservative should be considered even when likelihood is low since cells preserved in such solution can always be examined with routine cytological methods; however, cells that are placed in formalin or alcohol cannot be evaluated for flow cytometry. The use of rapid on‐site evaluation (ROSE) cytology has been shown in many studies to increase diagnostic yield and reduce the need for repeated procedures.

Читать дальше