Christophe RostyEnvoi Specialist Pathologists Brisbane Queensland Australia

Yutaka SaitoNational Cancer Center Tokyo Japan

Mounir TrimecheInstitute of Pathology University of Lausanne Lausanne Switzerland

Michael B. WallaceMayo Clinic Jacksonville Florida USA

Herbert C. Wolfen Mayo Clinic Jacksonville Florida USA

Naohisa YahaghiKeio University Cancer Center Tokyo Japan

1 General Principles of Biopsy Diagnosis of GI Disorders

Herbert C. Wolfen1, Michael B. Wallace1, Naohisa Yahaghi2 and Yutaka Saito3

1 Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, USA

2 Keio University Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan

3 National Cancer Center, Tokyo Japan

Tissue sampling of the gastrointestinal tract at the time of endoscopy is the cornerstone of many gastrointestinal diagnoses. The development of a flexible endoscope and the subsequent ability to directly acquire tissue under optical guidance has been one of the most important advancements in the field of gastroenterology throughout its history. Although tissue sampling can be performed through nonendoscopic devices, the ability to directly correlate precise locations and target biopsies to specific areas of disease is critical to our ability to diagnose and further understand gastrointestinal pathology. Many of the advancements in our understanding of the basic pathology and molecular biology of gastrointestinal disease can be directly attributed to our ability to acquire tissue for histological, molecular, and genetic analyses. An excellent example is our deep understanding of the molecular pathology of colorectal cancer development from normal colonic epithelium to adenoma to colorectal cancer, a discovery made possible because of colonoscopic access to precursor lesions such as adenomatous polyps and early cancers.

In this chapter, we will review general principles of tissue acquisition at the time of endoscopy including the following topics:

Endoscopic equipment for obtaining tissue including endoscopic accessory channels, biopsy forceps, snare devices, needle aspiration and cytology brush.

General principles of optimal sampling technique.

Methods of tissue preparation in the endoscopy laboratory to optimize diagnostic accuracy.

The role of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)‐guided fine‐needle aspiration cytology.

Endoscopic Equipment for Tissue Sampling

Modern endoscopic equipment can be divided in two general categories: the endoscope that allows access to the gastrointestinal tract and accessory devices that are typically passed through the working channel of the endoscope to directly acquire tissue, including biopsy forceps, snares, fine‐needle aspiration devices, and cytology brushes. Recent developments in tissue sampling include devices that are capable of wide‐field, often definitive, endoscopic resection of early neoplasia and invasive carcinoma.

A modern endoscope is a remarkably robust and versatile instrument including a light source, optical lenses with a video capture device, image processing, and display equipment, and importantly for the purposes of tissue acquisition, an accessory channel ranging from 1 to 6 mm (typically 3–4 mm), which allows passage of devices for mechanical collection of tissue ( Figures 1.1and 1.2).

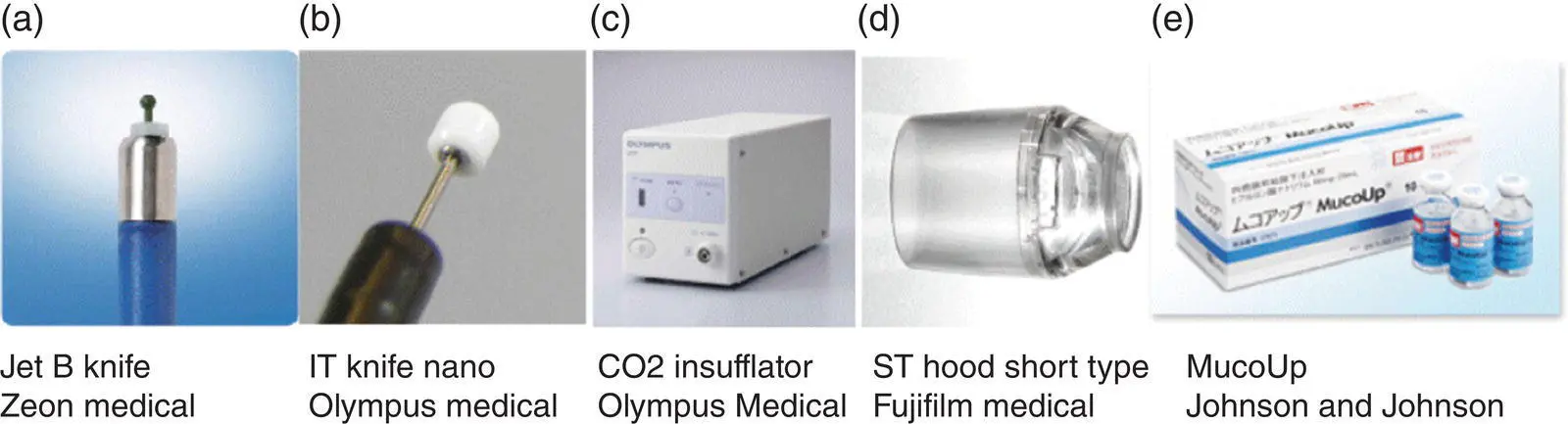

There is a general trade‐off between the diameter of the instrument and the ease and comfort with which it can be passed through the natural orifices of the body such as the mouth and anus. In general the larger the outer diameter, the larger the accessory channel is to accommodate larger instruments for tissue acquisition. A fundamental limitation of most flexible endoscopes, as opposed to surgical instruments, is that all accessories pass through a single access point of the endoscope. As compared to surgical instruments with multiple access points, the endoscopic devices do not typically allow triangulation to acquire a large bulk tissue or resect entire organs. For this reason, most tissue is sampled through pinch forceps, needle aspiration, or wire loop snare devices. More recently, electrosurgical needles and other cutting tools have been developed, which have allowed wide‐field resection of tissues of virtually any diameter ( Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.1 Endoscope with control handle and tip. The tip contains a light source, imaging window, and accessory channel through which various tissue acquisition devices can be passed.

Figure 1.2 Endoscopic processor, which converts the light captured from the endoscope tip into a visible image for display.

Source : Olympus America, Inc. With permission.

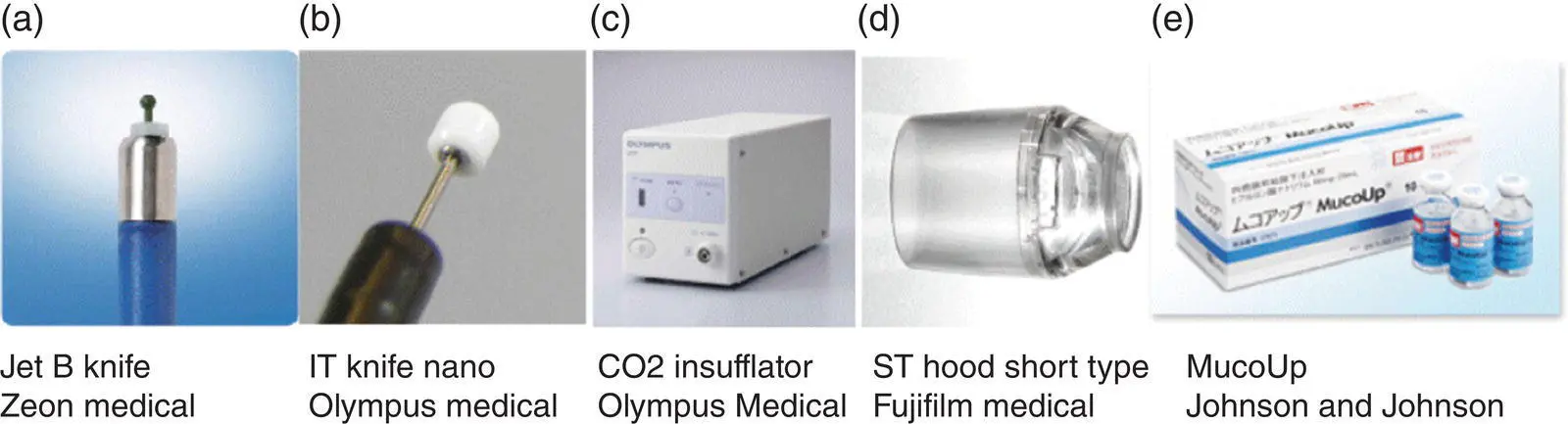

Figure 1.3 (a) Tools for performing endoscopic resection including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

Source : Zeon Medical.

(b) Standard and insulated tip electrocautery knives for incision and dissection.

Source : © 2017 Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

(c) CO 2insufflator for luminal distension, which is preferred to air given rapid reabsorption.

Source : Olympus.

(d) Distal attachment hood to facilitate maintaining view within the submucosal space.

Source : Fujifilm medical.

(e) Injection fluid (hyaluronic acid; Mucoup [Johnson and Johnson]) for submucosal lifting.

Source : Gut and Liver.

The flexible pinch biopsy forceps have been one of the most versatile of all instruments for tissue acquisition. These typically involve a flexible steel cable and lever device with two sharp‐edged cups, which can be opened and closed to acquire tissue ( Figure 1.4).

Standard endoscopic sampling typically acquires tissue from the mucosa and occasionally a submucosal depth of the intestinal wall; however, large‐capacity forceps as well as multiple sampling including “bite on bite” allow sampling of the deeper layers. Pinch biopsy forceps come in multiple sizes from very small instruments such as a pediatric forceps, which can be passed through very small working channels. Recent development of very tiny forceps makes it possible to pass them through special endoscopes into the bile or pancreas duct and to pinch biopsy outside of the traditional gastrointestinal lumen ( Figure 1.5).

Studies comparing jumbo forceps to standard forceps have generally not shown significant advantages of larger capacity forceps. A limitation of most forceps is the inability to sample tissue in the submucosa routinely. This is highlighted in studies looking for Barrett's esophagus after the surface epithelium has been ablated. Biopsy forceps can remove tissue with mechanical closure alone or with electrocautery (“hot biopsy”) although the use of hot biopsy has diminished significantly due to increased risks of complication and tissue damage in the biopsy specimen.

Читать дальше