Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Definition, General Features, Predisposing Factors

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EOE) is a chronic, immune‐mediated or antigen‐mediated inflammatory condition characterized by symptomatic esophageal dysfunction and eosinophil predominant mucosal inflammation. EOE represents a type 2 (Th2) helper T cell and cytokine‐mediated disorder involving genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and allergic background. Food‐based antigens appear to be the dominant mediators of EOE, although aeroallergens may also act as triggers in susceptible patients.

Since it was first established as a distinct clinicopathologic entity in 1993, EOE has become an increasingly recognized cause of dysphagia and esophageal dysfunction, particularly among patients refractory to medical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

EOE is reported worldwide, with highest prevalence in the United States and Western Europe. It occurs more frequently in children and young adults, although it is increasingly recognized in older adults, and is more common in males (male‐to‐female ratio of 3–4 : 1). A history of other allergic conditions may be present, such as asthma and atopic dermatitis, as well as peripheral eosinophilia, which are more common in children.

Current diagnostic criteria for EOE include a combination of clinical and pathologic features ( Table 2.3).

Table 2.3 Definition of eosinophilic esophagitis and diagnostic criteria.

| Symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction |

| Eosinophil‐predominant inflammation on esophageal biopsy, characteristically consisting of a peak value of ≥15 eosinophils per high‐power field (EOS/HPF) |

| Mucosal eosinophilia is isolated to the esophagus and persists after a PPI trial |

| Secondary causes of esophageal eosinophilia excluded ( Table 2.5) |

| A response to treatment (dietary elimination; topical corticosteroids) supports the diagnosis of EOE, but is not required. |

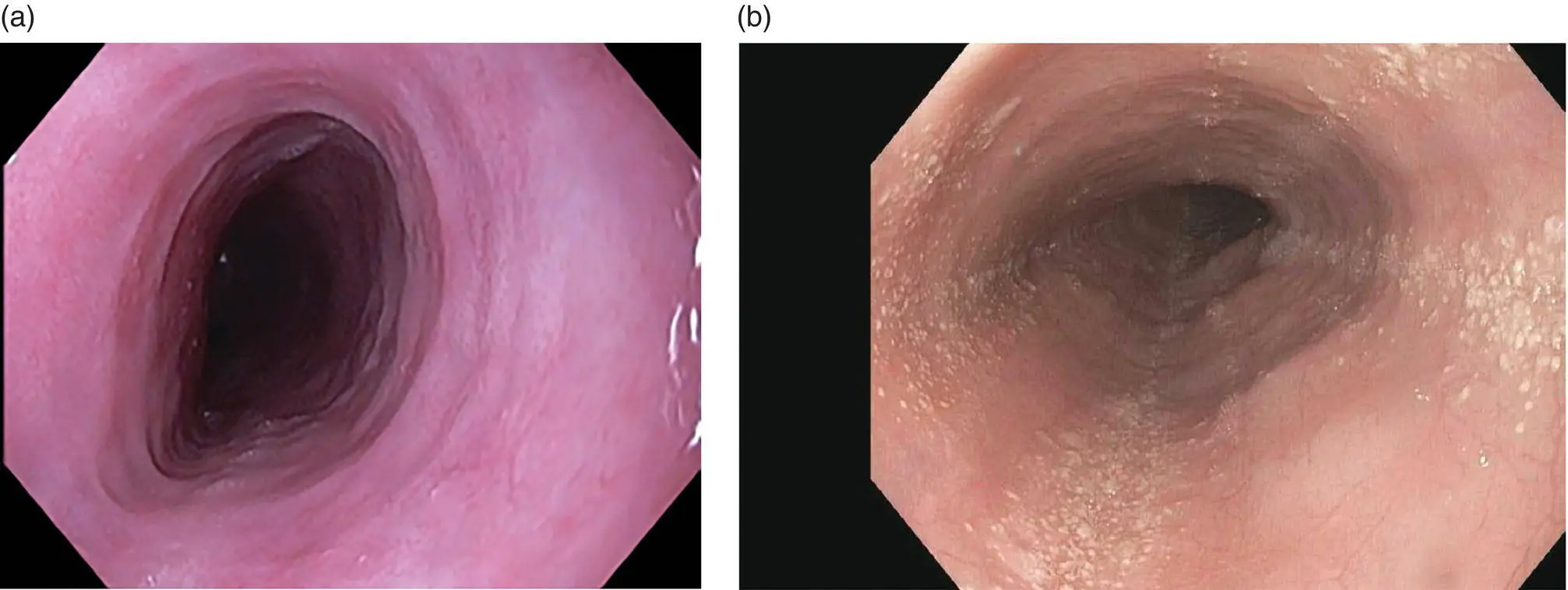

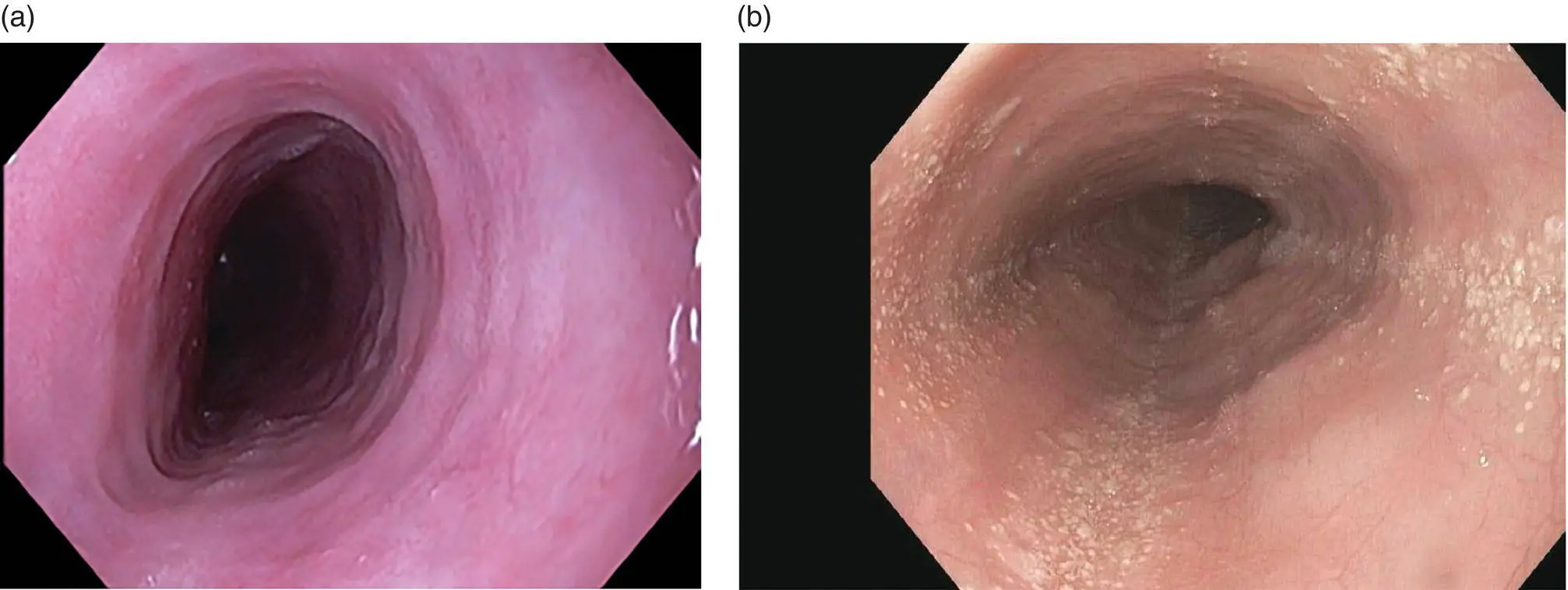

Figure 2.12 Endoscopic appearance of eosinophilic esophagitis (a) with so‐called feline esophagus appearance and (b) with extensive white microabcesses. Subtle circular rings and longitudinal furrows also present.

Clinical Features and Endoscopic Characteristics

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EOE) is increasing in prevalence and often seasonal with spikes during typically airborne allergy season. It presents with dysphagia to solids, classically with pills sticking. Other atopic symptoms are common. At endoscopy, the esophagus has white punctate spots (eosinophilic microabscess), rings, longitudinal furrows ( Figure 2.12), and desquamates easily with insufflation or dilation. In late stages, the esophagus may be very narrowed and poorly distensible.

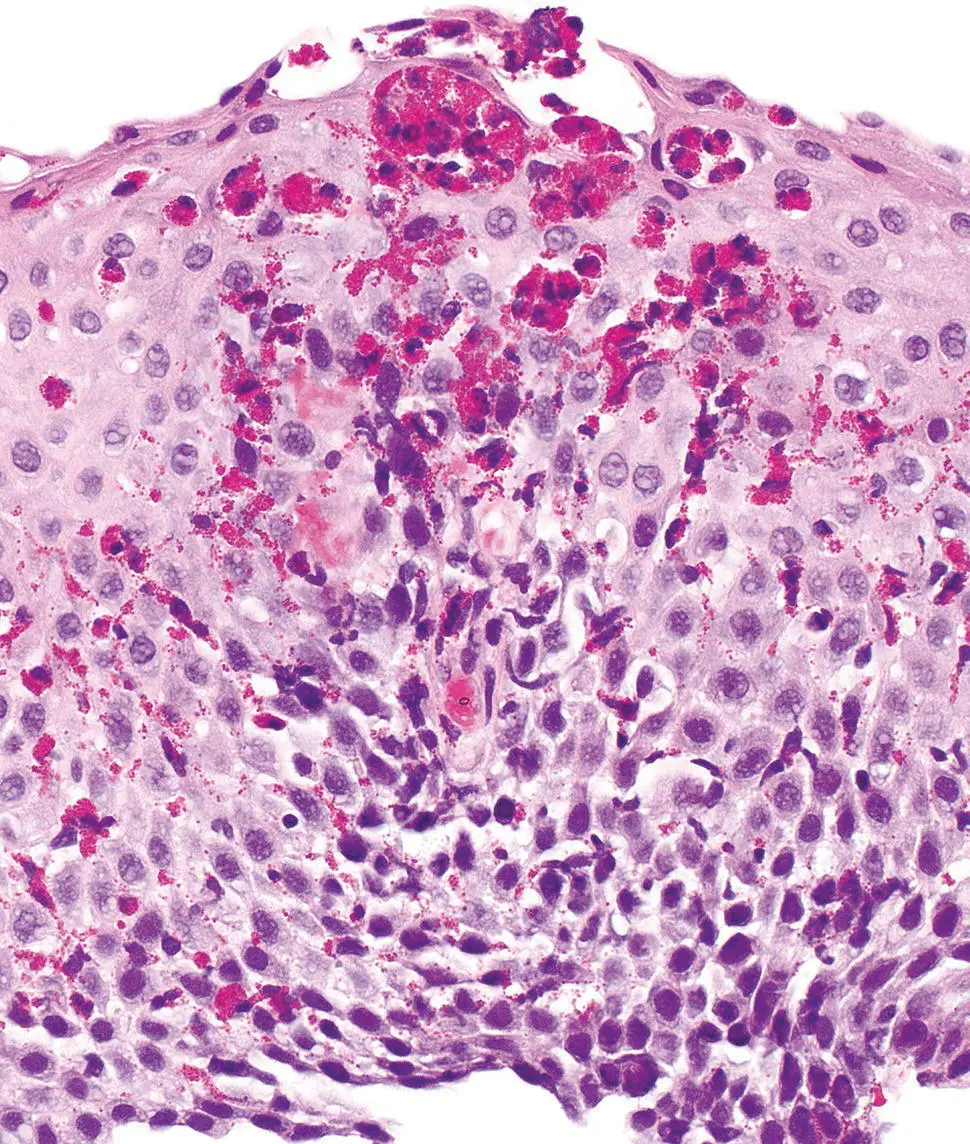

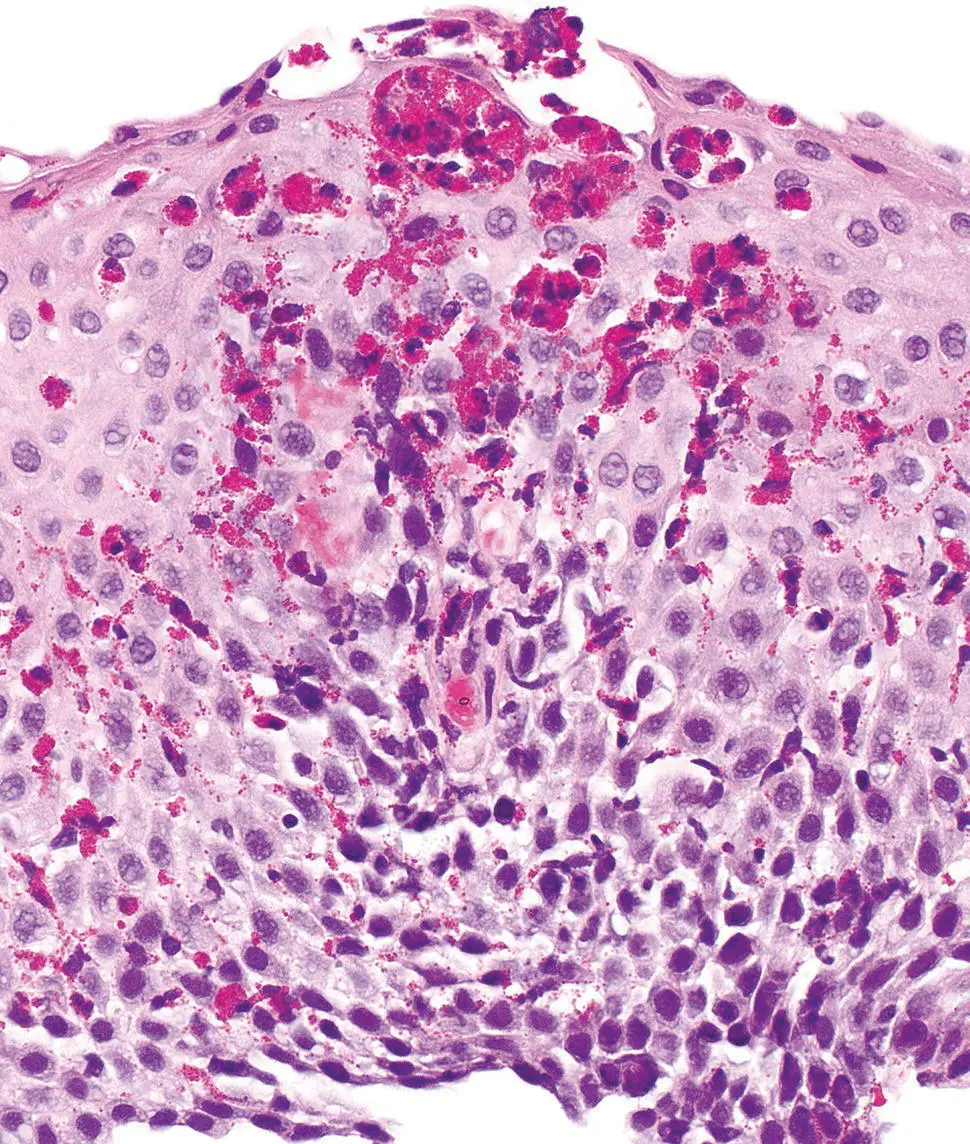

Esophageal biopsies are required to diagnose EOE. Eosinophils are generally absent from the esophageal squamous epithelium in normal individuals. The histologic hallmark is the presence of an increased number of eosinophils within the squamous epithelium ( Figure 2.13). Although there is no exact threshold number that establishes a diagnosis, 15 eos/HPF (peak count) in at least one biopsy is considered a “minimum” threshold.

Eosinophilia may be patchy, and it is recommended that two to four biopsies from at least two locations in the esophagus should be taken to maximize diagnostic yield. The distribution of eosinophilia is important, as they may be identified in both proximal and distal biopsies or be more prominent in proximal biopsies. Practically, only intact eosinophils with visible nuclei should be counted and eosinophilic granules should not be included, although degranulated eosinophils may be a useful clue.

Other histologic findings may be present although none of these should be considered pathognomonic. These features include moderate‐marked reactive basal hyperplasia, eosinophilic microabscesses (superficial aggregates of ≥4 eosinophils), superficial layering of eosinophils, and subepithelial fibrosis. The presence of subepithelial fibrosis is also associated with eosinophils in the lamina propria and correlates with fibro‐stenotic complications of EOE, but may not be identifiable depending on biopsy depth. Other inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and mast cells, can also be increased. When reporting the cases, a note is useful to summarize additional relevant histologic features and to provide an overall assessment of the case based on all available biopsies (including prior biopsies, if applicable). For example, active esophagitis with intraepithelial eosinophils (peak count of # per HPF) followed by a note. When large numbers of eosinophils are present (e.g. >40 per HPF), an exact count may be difficult and it is appropriate to report the peak count as such (e.g. “peak count of >40 per HPF”).

Figure 2.13 Characteristic histology of eosinophilic esophagitis with basal cell hyperplasia, marked eosinophilic infiltrate with eosinophilic microabscesses.

Immunohistochemical Studies and Molecular Features

Currently, the examination of esophageal mucosal biopsies by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections, with clinical correlation, remains the most reliable diagnostic test for EOE. The diagnostic value of ancillary studies in distinguishing eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease and other conditions remains unproven.

Immunohistochemical stains targeting eosinophil peroxidase, major basic protein, and eosinophil‐derived neurotoxin, have been reported to enhance detection of eosinophils compared to evaluation of H&E sections, but these stains are not widely used in routine clinical practice. A recent study suggested that the presence of intra‐squamous IgG4 deposits by immunohistochemistry may be a useful adjunctive marker for EOE.

Molecular analyses of esophageal tissues, such as gene expression analysis of chemokines such as eotaxin‐3 (CCL26), and transcriptome analysis show promise to improve diagnosis and clinical monitoring, and to guide patient‐specific therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical

Dysphagia and rings in the esophagus can occur from any inflammatory condition. Even eosinophils may be present in GERD alone. EOE typically requires a confirmatory biopsy from the upper and lower esophagus showing eosinophilic infiltrates. Desquamative conditions that should be excluded include bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus. These typically require deep biopsies and special immunofluorescence staining; thus, communication between endoscopist and pathologist is critical.

The histologic appearance of EOE is not specific, and mucosal infiltration by eosinophils is a component of a variety of other esophageal inflammatory conditions ( Table 2.4).

GERD and PPI‐responsive esophageal eosinophilia exhibit considerable histologic overlap with EOE. In an untreated patient, fewer numbers of eosinophils with distal predominance may be suggestive of GERD. Correlation with response to PPI therapy is paramount.

In eosinophilic gastroenteritis, obtaining biopsy specimens from the stomach and duodenum and other clinical symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may be helpful in establishing a diagnosis.

Читать дальше