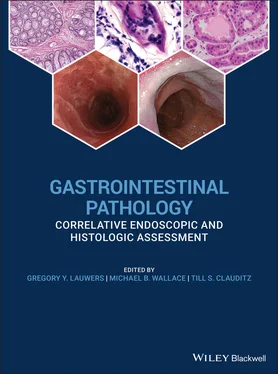

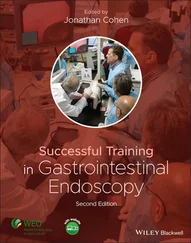

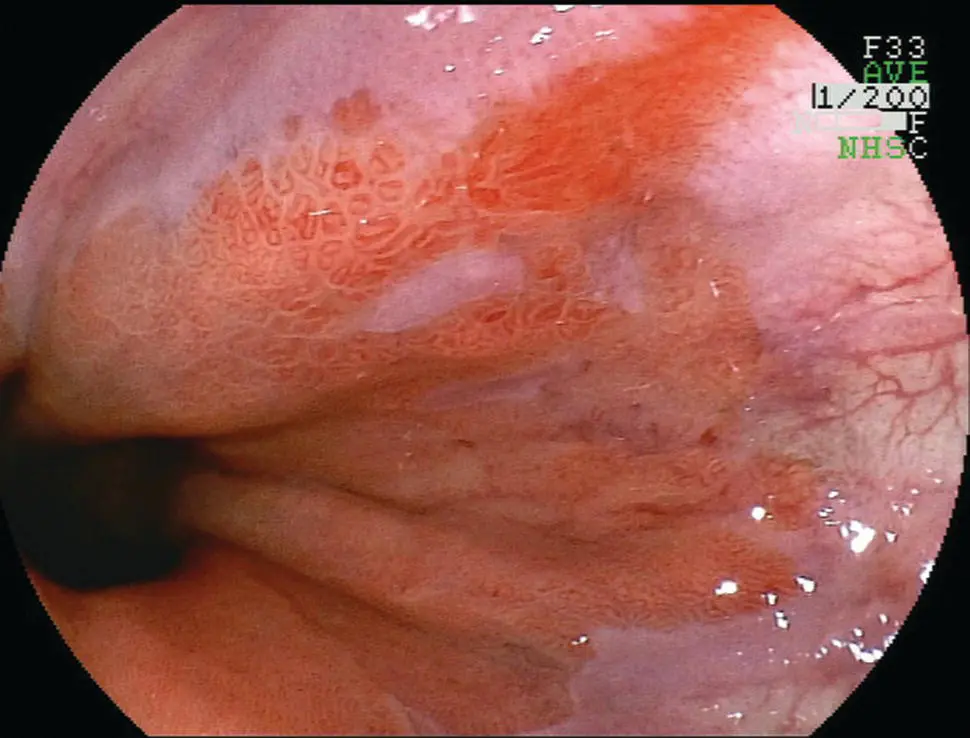

Figure 2.9 Endoscopic appearance of erosive esophagitis in a patient with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Grade C: at least one mucosal break that is continuous between the tops of 2 or more mucosal folds, but which is not circumferential.

Grade D: a circumferential mucosal break, erosions and ulceration, often resulting in scarring and stenosis if the reflux is recurrent.

Mucosal bridges and esophagogastric fistulae may be encountered.

The endoscopic findings in reflux esophagitis have been classified into three main stages: active, healing, and scarring. Relapse and healing occur repeatedly in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and a mixture of the stages is often seen in biopsy specimens.

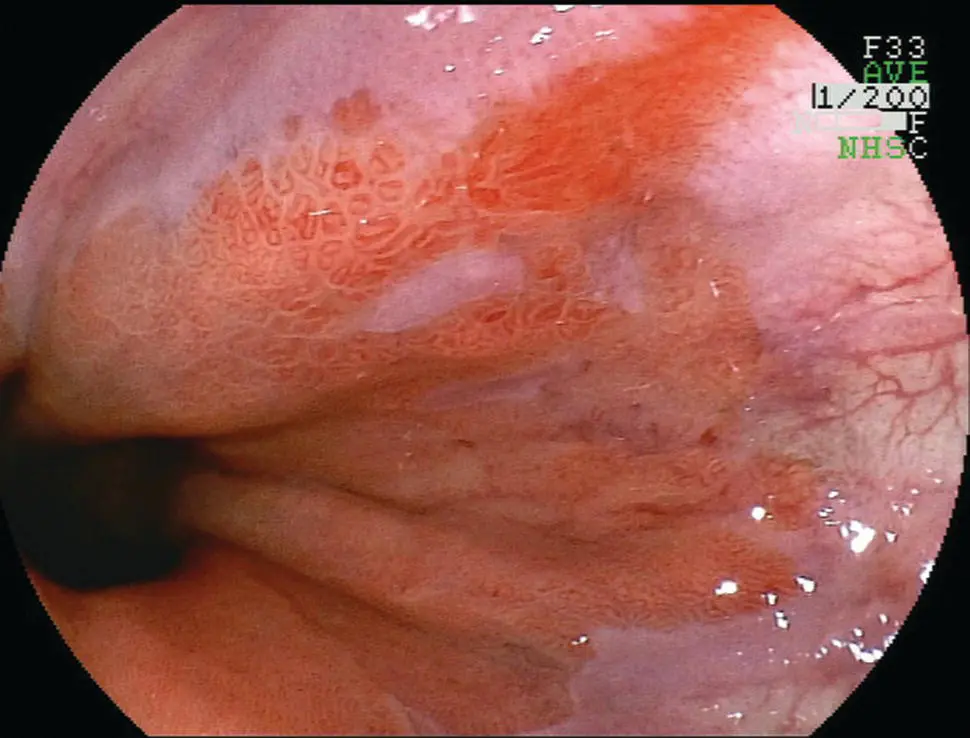

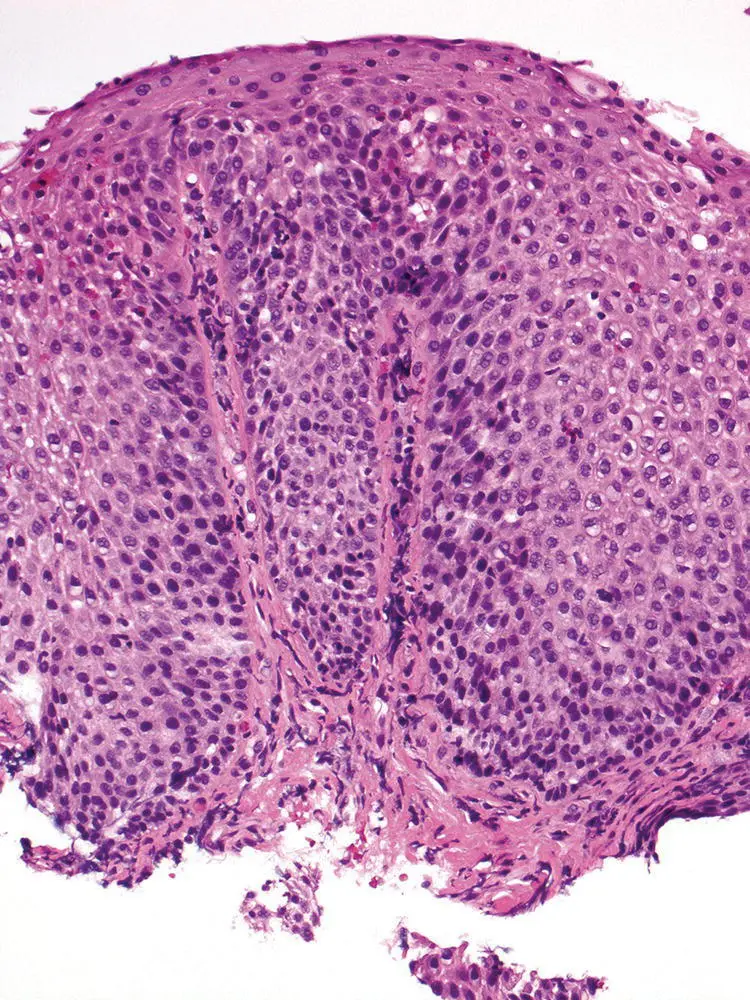

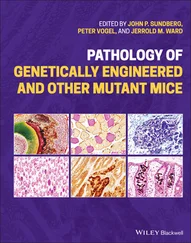

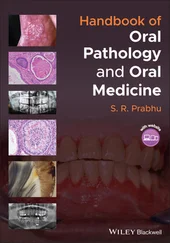

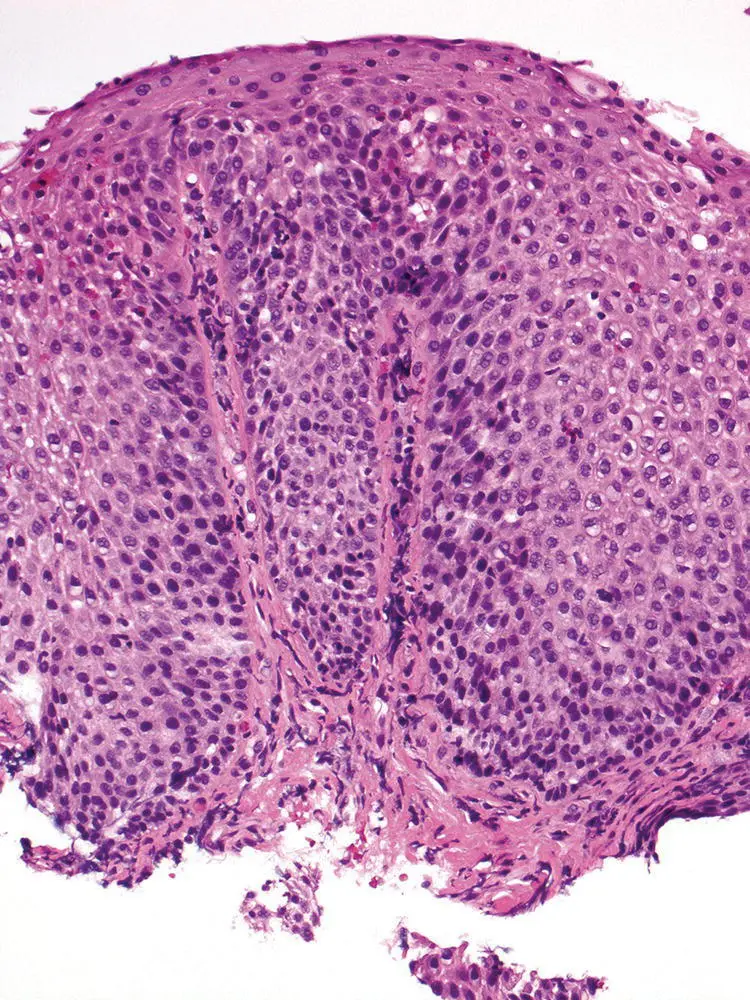

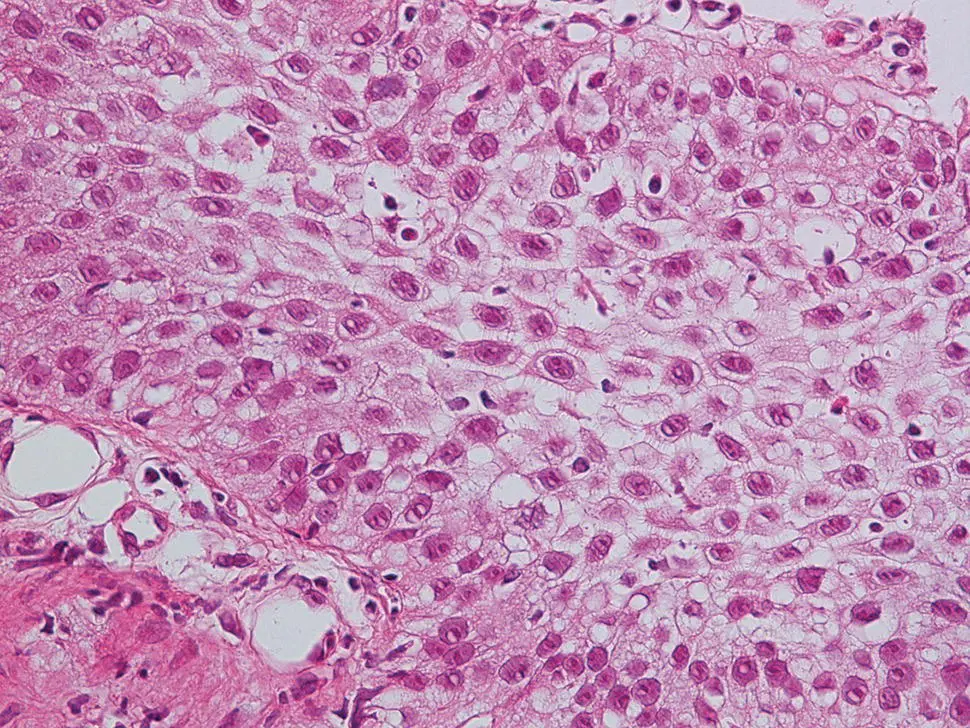

The typical features of GERD are basal cell layer hyperplasia, papillary elongation, dilated intercellular spaces (intercellular edema/spongiosis), and intraepithelial inflammation, including neutrophils, eosinophils, and mononuclear cells ( Table 2.2; Figures 2.10, 2.11). However, none of these features is specific for this diagnosis.

The proliferative epithelial changes are more common than inflammatory infiltration. Basal cell hyperplasia is diagnosed when the thickness of the basal layer exceeds 15% in a well‐oriented section. Papillary elongation, defined as extending >50% of the epithelial thickness, should also be only assessed in well‐oriented sections. Finally, in minimal GERD, dilated intercellular spaces in the basal and parabasal areas may be the only finding.

Esophageal squamous mucosa normally contains few or no inflammatory cells and the inflammatory infiltrate in GERD is highly variable. The presence of occasional eosinophils is typical of GERD, although large numbers of intraepithelial eosinophils mimicking eosinophilic esophagitis may be identified. Notably, eosinophils are not found in all GERD biopsies and can be seen in asymptomatic patients. Neutrophils may be present, and are more numerous in areas of erosion and ulceration. Lymphocytes, often with irregular nuclear contours (squiggle cells), are usually scattered through the epithelium. Finally, severe inflammation with ulceration may be associated with inflammatory pseudotumor formation, with marked atypia of the reactive stromal cells.

Table 2.2 Histologic features of GERD.

| Basal cell hyperplasia (>15%) |

| Papillary elongation (>50%) |

| Dilated intercellular spaces (spongiosis) |

| Intraepithelial inflammation Neutrophils |

| Eosinophils |

| Mononuclear cells |

Figure 2.10 Characteristic appearance of low‐power view of reflux esophagitis with basal cell hyperplasia, elongation of papillae, lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate.

In practice, the report should provide a descriptive summary of the histologic features and injury patterns present, as well as their severity. A note can be added to state that the findings are compatible with reflux injury pattern in the appropriate clinical setting.

Figure 2.11 High‐power magnification of reflux esophagitis with basal cell hyperplasia, spongiosis, and eosinophilic infiltrate.

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical

Clinically, erosive esophagitis from GERD is typically in the lower third of the esophagus and contiguous with the gastroesophageal junction as opposed to other inflammatory or infectious etiologies that may occur more proximally. The presence of a normal distal esophagus with more proximal inflammation virtually excludes GERD‐associated inflammation. Typical symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation. Ph‐ metry (monitoring the acid reflux events by a wired or wireless sensor in the distal esophagus) can be used in challenging cases but is rarely necessary with obvious symptoms and when esophagitis is seen.

As none of the histologic features are specific for GERD, other etiologies such as infection, eosinophilic esophagitis, iatrogenic injuries, Crohn's disease, and inflammatory skin disorders involving the esophagus may enter into the differential diagnosis.

The presence of large numbers of neutrophils in the superficial epithelium should suggest the possibility of fungal infection or superinfection, and special stains (PAS‐diastase, GMS) should be performed to exclude Candida organisms. Large numbers of intraepithelial eosinophils raising the possibility of eosinophilic esophagitis and correlation with clinical findings and PPI treatment status are required (see Section “ Eosinophilic Esophagitis”). Numerous intraepithelial lymphocytes, if predominant, may suggest an alternative diagnosis such as lymphocytic esophagitis or lichen planus‐associated esophagitis (see Sections “Lymphocytic Esophagitis” and “Dermatological Diseases Involving the Esophagus”).

Ulceration with regenerative squamous epithelial atypia may be difficult to distinguish from in situ‐squamous cell carcinoma and dysplasia. The regenerating epithelial cells have round nuclei with minimally thickened nuclear membranes; fine chromatin; and large, irregular nucleoli, and generally have abundant cytoplasm. Further, maturation toward the epithelial surface can usually be found. In difficult cases, additional biopsies should be requested after medical treatment of the esophagitis. However, in some cases, inflammatory pseudotumors with marked atypia of the reactive stromal cells will need to be differentiated from poorly differentiated carcinoma or sarcoma. Cytokeratin immunohistochemistry (IHC) may be helpful when trying to distinguish between reparative reactions and malignancy.

Less commonly, activated lymphocytes in areas of ulceration may appear atypical and raise the suspicion for lymphoma. In some cases, immunohistochemistry and/or flow cytometry may be necessary to assess for clonality.

Prognosis, Evolution, and Clinical Management

GERD management is based on the severity and potential for complications and largely consists of lifestyle modification, anti‐acid medications or surgery. Most nonerosive or minimally erosive (Los Angeles Grade A) responds to a combination of lifestyle modifications and low‐dose (single daily proton pump inhibitor [PPI] such as omeprazole) anti‐acid therapy. Lifestyle modifications include weight loss, avoiding large meals with two to three hours of bedtime (where gravity no long prevents “upward” reflux), and minimizing specific refluxogenic foods (alcohol, mint, fatty food, chocolate, caffeine). PPI therapy is highly effective, even for severe erosive GERD but may require twice‐daily therapy. More than 95% of patients will heal erosive disease on PPI therapy.

Surgical therapy is aimed at restoring the lower esophageal sphinter pressure zone and angle of His, and reducing hiatal hernias. Surgery is also highly effective with more than 80% of individuals having sustained elimination or reduction in GERD symptoms and use of PPI. The major side effect of surgery is retention of gas in the stomach (“gas‐bloat syndrome”) due to the inability to naturally belch swallowed air.

Читать дальше